© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Russian Shipping

In a remarkably short time the Soviet Union has built up a considerable mercantile marine with the object of handling all Russia’s overseas trade in Soviet ships. Unparalleled measures have been taken to achieve this end with efficiency

SEA TRANSPORT OF THE NATIONS -

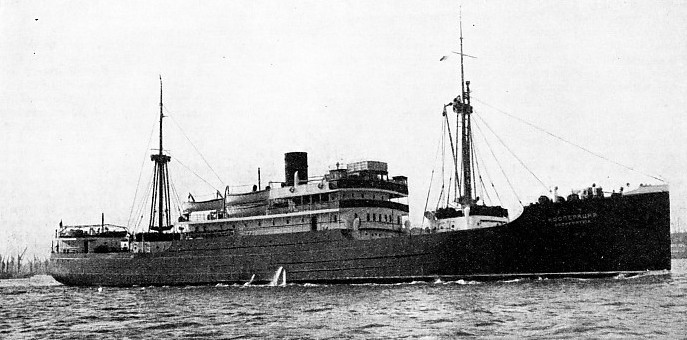

A SOVIET MOTORSHIP of 3,767 tons gross, the Cooperatzia was built in 1929 at Leningrad, formerly Petrograd and originally St. Petersburg. She has a length of 332 ft. 6 in. between perpendiculars, a beam of 48 feet and a moulded depth of 27 ft. 9 in. Her two-

ONE of the most extraordinary incidents in the commercial history of the twentieth century is the development of the Russian shipping industry as it is to-

The Soviet Government, which owns the entire Russian Merchant Service, has set out with the definite aim of handling the whole of Russia’s overseas trade with its own ships. The usual aim is to handle half the trade, leaving the other nations the other half, and even that aim has proved to be beyond the power of most countries. The effect of the Russian policy must be watched with interest and with a good deal of apprehension, lest it should be taken to its logical conclusion of every country carrying its own exports, so that every ship must spend half of her time in ballast.

That situation is still a long way ahead. What is of more immediate importance is that the Russian Government couples with this aim the scheme of making Russia the second shipping power in the world by the end of the third Five-

Attention devoted to the Navy in the Far East and Europe must, under the Russian system, be taken from mercantile interests and the future of the Russian Navy is beyond all calculations.

Immense progress has been made. The 3,970,000 tons of cargo which were carried in Soviet ships — sea-

The introduction of such a volume of new tonnage at a time when the world’s market was already heavily overstocked naturally had its effect on shipowning all over the globe. The new Russian Merchant Service had to be studied carefully by every shipping man who came within range of its competition.

In 1913 Russian ships transported nearly 50,000,000 tons of cargo by sea and river and, with the poorly developed railway system, the coastal and internal waterway services were of the greatest importance to the country. Russian ships, however, were responsible for only about 11 percent of the overseas trade.

The ships and sailors which carried the Russian flag overseas mostly belonged to those Baltic provinces which are now independent republics, and with few exceptions the Russians themselves had no taste for deep-

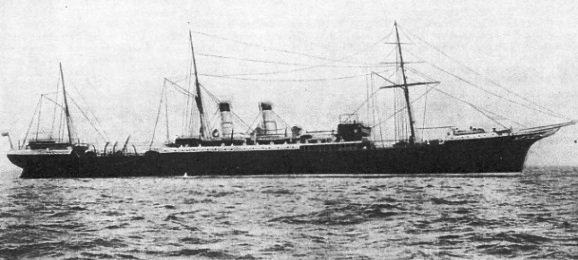

IN THE VOLUNTEER FLEET. The Russian Volunteer Fleet was formed in 1878, and its cruiser-

The old Tsarist Government appreciated the importance of the subject well enough, but its efforts had little success. It established a shipping subsidy system which was one of the most generous in Europe to the services in which it was interested. Official help was given to the formation of the famous Russian Volunteer Fleet in 1878, whose cruiser-

Many enthusiasts who brought forward schemes for the development of the shipbuilding or shipping industry found generous help in high places. Huge sums were paid out by the Imperial Treasury, but the results were meagre. One or two companies, spoon-

Lenin signed the decree for the nationalization of all Russian shipping in February 1918, at a time when private owners possessed seventy-

When the nationalizing decree was signed the ships that were out of Russian waters naturally stayed out, and a number of the directors of the Russian Volunteer Fleet escaped to Paris and conducted their business from there.

Work, But No Pay

During the war of 1914-

In the early days of hopeless disorganization little effort was made to use the merchant ships which the Russian Government owned, and overseas trade was at a standstill. By the beginning of 1922 the authorities had all the existing ships that they were likely to obtain.

Lenin was one of the few Soviet rulers who appreciated the importance of the shipping industry, and how it could help in the formation of the new State. He was also far shrewder than some of his colleagues and, although he had been instrumental in securing the nationalization of the Merchant Service, he encouraged a measure of private ownership on more than one occasion when it appeared advisable. After the bad harvest of 1922 he even formed mixed shipowning companies in partnership with foreign capitalists.

In a country whose administration was founded on a political belief it was difficult or impossible for anybody with a less assured position than Lenin to go against that principle, even when the circumstances of the time demanded it, and after his death his successors could not make the same concessions. The definite policy was the complete nationalization of all industries, and from the political viewpoint shipping was one of the most important.

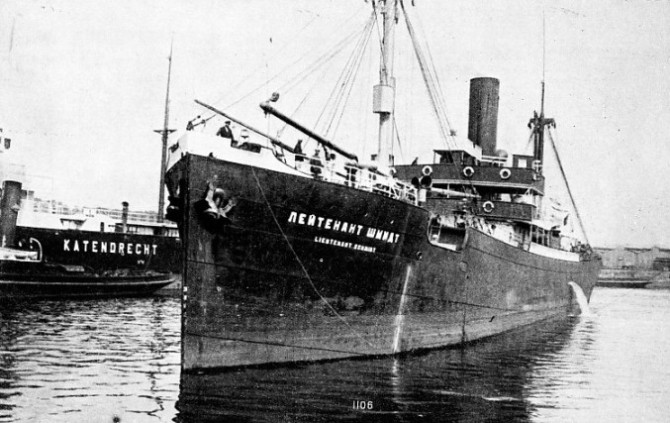

A RUSSIAN SHIP’S NAME is often transliterated on her bows for the benefit of those who do not understand the Russian characters. The Lieutenant Schmidt, a vessel of 2,492 tons gross, was built at Rostock, Germany, in 1913, as the Frascati. She is registered at Vladivostok, the “Mistress of the East”, on the coast of the Sea of Japan. The length of the Lieutenant Schmidt is 297 ft. 3 in., her beam 40 ft. 1 in. and her depth 15 ft. 7 in. In the left background is the Katendrecht, a Dutch vessel of 5,099 tons gross.

Steps were therefore taken to increase the status and efficiency of the industry, for which new and better ships were needed, but Russia had never been a commercial shipbuilding country. Surprisingly few steamers of any size had ever been built in Russian yards. The naval establishments existed for the Navy only, and commercial ships had always been bought abroad. Those produced in Russia were mostly river and coastal craft only, more often than not built of wood.

Russia had, for the time at least, no intention of reviving the Navy, so that the naval dockyards on which the former Government had spent huge sums were converted to the work of building up the merchant fleet. The yards had not been designed for this, and it was not easy to adapt them. They had been derelict for a long time while the machinery was deteriorating or being looted. It wanted mu-

An essential part of the plan was that the whole work should be carried out in Russia, by Russian labour and as far as possible with Russian material. But the shipbuilding industry could not tackle the work at once, and at first it was necessary to go abroad. German shipbuilders gave long credit with the assistance of their Government and were most favoured. The Free City of Danzig obtained some orders, as did also Italy, but the question of credits always made a difficulty, and without the help of their Government the British shipbuilders were unable to benefit.

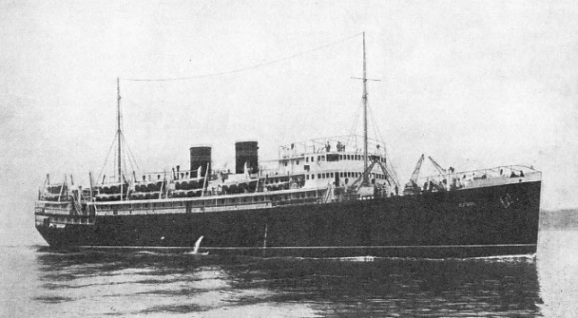

BUILT AT KIEL, GERMAN, in 1928, the Krym is a twin-

These foreign orders, however, were intended only to see the plan over its first difficulties. There was never any intention of building more than a few ships in that way while an immense organization was being perfected. The new Russian Merchant Fleet was to consist entirely of modern motorships and, while the naval dockyards and such few private yards as existed were mobilized for the building of the hulls, the gigantic Sojus Diesel Engine Works were built for the construction of the machinery.

Ruthless Scrapping

The all-

The idea of having the merchant service composed entirely of modern motorships was never abandoned. In spite of the difficulties with the straightforward diesel, many of the ships later planned were designed with far more complicated and delicate diesel-

As mistakes were revealed they were rectified. Faulty machinery was ruthlessly scrapped and replaced by more efficient machinery. All the time the greatest care was being paid to technical education and training.

Meanwhile steps were taken to buy enough ships abroad to carry out the necessary work until the new ones were built. Several cargo steamers were bought from the United States Shipping Board, and many from private owners in Europe. Nearly all were vessels which had been laid up for a long time and which were apt to give trouble. The tankers bought were all first-

ICE-

No more ships were bought than was absolutely necessary, for they were intended only to tide the service over until the new ships should be completed. As far as possible foreign tonnage was chartered instead of being bought, and taken up only when it was needed. A large amount of tonnage was used in the seasonal timber business, although there were difficulties to be overcome in chartering terms, ice-

All the time the authorities were working steadily to improve the shipbuilding capabilities of Russia itself. Every naval dockyard which had been built by the old Tsarist Navy was carefully adapted for mercantile purposes and a number of entirely new establishments, designed on the most modern and scientific lines, were laid down and put into working order as quickly as possible.

Plant and personnel had to be built up almost from nothing and the task was gigantic.

Despite this the first Five-

The programme that was laid down would have been a task for the best organized shipbuilding country in the world with the same number of slips at its disposal. For Russia with so much to be built up from the bottom it was impossible. The programme was to include fifty-

Women Sailors

Labour was good, thorough and painstaking but terribly slow. Some of the shipyard managers proved unsuitable through their lack of knowledge and experience, but others did remarkably well. Standardization in design and specialization in the establishments were carefully studied and carried to great lengths.

If the Russians adopted unorthodox methods in the shipbuilding and marine engineering industries, these methods were no more original than those which had to be adopted on the shipping side. A department of the Soviet was formed as soon as the Merchant Service was nationalized in 1918. It was elaborated in 1920 and thoroughly reorganized two years later under the title of “The State Commercial Navy”. In 1923 the scheme was enlarged, and in 1925 the present Sovtorgflot was established which took into its hands all the owning and operating departments.

The organization and discipline of Russian ships are quite different from those of any other nation. The idea of running them by committees was quickly dropped; but, as with every other organization in the country, every ship has its workers’ representative and committee to deal with certain matters.

Women are to be found in most Russian ships, and nearly all the work of the stewards’ department is carried out by them. Many wireless operators of the fleet are women, and they have proved most satisfactory in that branch. Some work as sailors or deck officers, and at least one has been given the command of a ship.

One of the most interesting and picturesque sides of the Soviet Government’s shipping activities is the manner in which it has made use of the North-

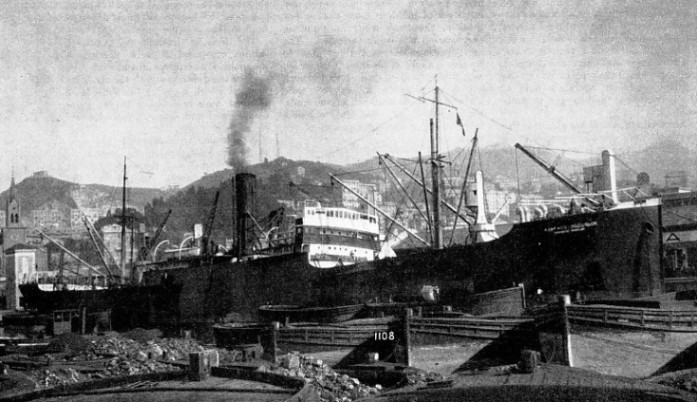

RUSSIAN SHIP AT GENOA. Against the romantic Italian background of the city of Genoa is outlined the profile of the Kamenetz-

You can read more on “Adventures of the Ice-

“The Chelyuskin Rescue” on this website.