© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Seattle, Washington

The largest city on the Pacific North-

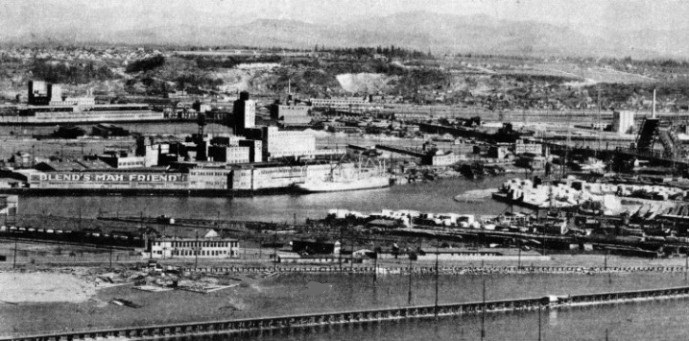

PIERS 40 AND 41 OF THE SEATTLE PORT COMMISSION claim to be the largest of their type in the world. Pier 40 has seven sheds each as large as the ordinary pier’s transit shed. Pier 41 can berth four vessels as large as the Queen Mary. There is a depth of 35 feet alongside at low tide. The piers are situated at the north side of Elliott Bay, which is an indentation of Puget Sound.

THE city of Seattle, which lies on a series of hills, has a population of about 400,000. Lake Washington, twenty miles long and two miles wide, forms its eastern boundary. Rolling back towards the east from the outskirts of the city is a series of undulating foot-

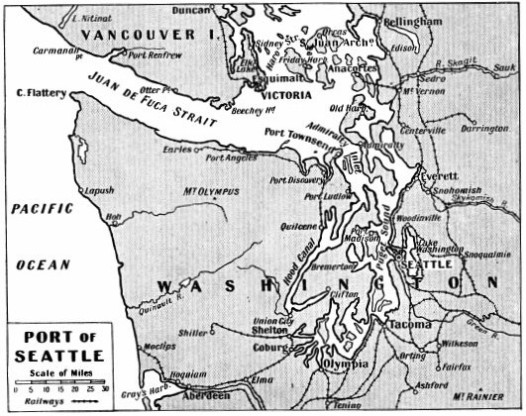

The city surrounds Elliott Bay, an indentation of Puget Sound. This bay forms the salt water harbour of Seattle, and is lined with wharves. The Pacific Ocean is 125 miles north and west of the city. It is reached through the waters of Puget Sound and of Juan de Fuca Strait.

Lake Union, within the city, and Lake Washington, on its eastern boundary, are joined to Puget Sound by the Lake Washington Ship Canal. The lakes form a fresh water harbour fifty square miles in area. In the salt water harbour there are 101 piers, including commercial wharves, industrial piers, ferry slips and fuel docks. In the fresh water harbour there are seventy-

Seattle is connected with the eastern States by four transcontinental railroads. Air lines from her municipal landing field span the continent, reaching the Mexican border on the south and Alaska on the north. Her water and land transportation facilities are supplemented by a modern and adequate municipal port. This organization, although it does not own or control all the waterfront, is the dominating factor in the water-

Seattle’s commercial and industrial growth are guaranteed by a wealth of natural resources. The finest and largest stand of timber in the world is in Western Washington. The salmon fisheries of Alaska are the largest in the world, and Seattle is the headquarters of the fishing industry. Western Washington, besides yielding the greatest quantities of lumber, is a large producer of canned fruits and vegetables, dairy products and manufactured articles. Eastern Washington bears one-

The story of Seattle’s rise to prominence among the world’s great cities cannot be told merely by an array of facts and figures. Eighty-

Seattle is young and, as is the way with youth, is intolerant. She breaks traditions without worrying much about them. The impossible is just another obstacle to her progress, and she makes every effort to overcome it. When hills stood in her path she washed them down into the sea, and along the level stretches thus made she erected shops and business establishments. When industrial sites were in demand she filled her tidal flats for many square miles and erected thereon her railroad stations and yards, her manufacturing plants and airports. Her spirit of self-

The first white settlers landed from the schooner Exact at Alki Point (West Seattle) in November 1851. There were in the party seven men, five women and twelve children. They had come by ox team across the plains and mountains and, for a short journey down Puget Sound, on the deck of a small schooner. It is significant that they came not, as did the gold diggers of California, seeking quick riches in the streams and as quick a return to their old homes in the East, but as homesteaders. Having spent the winter at Alki, they moved across Elliott Bay. There they built their permanent log cabins and established the nucleus of a little settlement. The trees that they felled for clearing they hauled with their oxen down to the bay, as logs and piling were in demand for building purposes in San Francisco. Soon they had a shipload of logs and the schooner Leonora took them south. This was the beginning of Seattle’s water-

SITUATED 125 MILES FROM THE PACIFIC, and reached through Juan de Fuca Strait and Puget Sound, the Port of Seattle is accessible and sheltered. The city surrounds Elliott Bay, an indentation of Puget Sound that forms the salt water harbour.

A Dr. Maynard, finding his professional services in little demand among the sturdy inhabitants, and with an eye for future business, salted a barrel or two of salmon, of which there was an abundance in the bay, and these he sold at a profit in San Francisco. About this time two brothers, experimenting with salmon in the Sacramento River, discovered the process of vacuum sealing and preserving the fish in cans. These men were the pioneers of the great fishing industry on the Pacific Coast.

Other settlements sprang up along the shores of Puget Sound, the most progressive of which was the town of Tacoma, some 30 miles south of Seattle. The rivalry for supremacy between these two towns was intense. In 1861 there came to Seattle a man who, in his evil way, was nevertheless the influence that weighed the balance of power in favour of Seattle.

John Pennell had no altruistic ideas concerning moral or civic betterment. Tall, saturnine and suave, wearing a flowered waistcoat, plug hat and a waxed moustache, he was the living model of what the well-

Pennell saw his opportunity of making money by pandering to the worst in the rough element that formed the greater part of the settlement at Seattle. At his “Palace of Pleasure”, which he built on the tide flats, the loggers and lumberjacks drank “red-

Compared with the drab life of the logging camps back in the bush, this “Palace” was an oasis in a desert, and drew crowds of loggers and miners from all over the territory. Seattle became recognized as the Mecca for those who had money to spend on a good time. They came in thousands to spend their holidays in Seattle. Seattle became known far and near as a wide-

The merchants secretly appreciated the prosperity that Pennell brought. Between them, nearly all the wages earned stayed in the community. This was enough to create a surplus, and in the course of time served a good purpose, for when the Northern Pacific transcontinental railroad decided to make Tacoma its Pacific Coast terminus, there was enough money in Seattle for the citizens to start building a railroad of their own. The undertaking was of sufficient magnitude to cause the executives of the railroad to change their minds and make Seattle the terminus.

Pennell, however, and others of his kind who had opened up shop in Seattle, were anathema to the better element. Probably the men were not so concerned as their wives, but the wives dominated the situation. These good women were striving to bring culture and decency to the town. Two of the more puritanical inhabitants, Asa and Thomas Mercer, borrowed a leaf from Pennell’s book, added a page from colonial history, and loaded a ship in the east with women. These were to establish decent married families in the settlement. The adventure was one of the most amazing incidents in pioneer history. It was partly successful, for it made Seattle conscious of its “better element”.

Pennell and others of his kind are not heroic figures. He was in no sense the character for which monuments are built, yet he served a purpose. He was a product of the times. His intellect was attuned to the popular demand. By correct judgment of the human elements he made Seattle the major attraction, the big town among the towns that were contesting for supremacy. By arousing the ire of the respectable citizens he gave impetus to the war on vice, without which cities become stagnant.

HANFORD STREET TERMINAL, showing the 1,500,000-

It seems to be the fate of most wicked cities to suffer a major calamity. These catastrophes in a measure purge them of their sins. These sins are not altogether based on human wickedness, but include many errors of mismanaged city planning and inadequate protective measures. In 1889 Seattle suffered one of these disasters. It started with a carelessly thrown match among the shavings in a cabinet shop near the waterfront. Before night the whole business section of the town was ablaze, and for several days street after street of shops and homes fell before the onslaught of the flames. When the fire had been got under control Seattle was almost wiped out.

It was then that the spirit of Seattle’s citizens showed itself most nobly. While the town was still burning news came of the Johnstown, Pennsylvania, flood, in which many lives were lost and there was much human suffering. Forgetting their own misfortune the people of Seattle, good and bad, sent contributions to the suffering city 3,000 miles away. They refused aid for themselves and set about rebuilding their own city. On lots where ruins still smoked they pitched tents, assembled food and supplies, and began again their business and community life.

In a way the fire was a benefit to Seattle. It destroyed all the red brick monstrosities that were an architectural feature of that period. Other towns less fortunate still have these eyesores, poked here and there among the modern buildings. Seattle widened her streets and laid foundations for her present beautiful business blocks of stone and cement, faced with terra-

Seattle in 1897, however, was still primarily a logging and lumbering town. She had a population of 45,000. She had not yet made her mark beyond the Pacific Coast. Her trade was principally coastwise, although Captain James Griffiths, backed by Jim Hill of the Great Northern Railroad, had negotiated successfully with the Nippon Yusen Kaisha for regular steamship services between Seattle and the Orient. A few steamers were on the run between Seattle and Alaska.

One of these, the Portland, came into Seattle in the summer of 1897 loaded with wild-

Seattle drew the gold-

LEVEL TRACTS FOR INDUSTRIAL PURPOSES were acquired by filling many square miles of tidal flats. On these sites were built railroad stations and yards, mills, factories and airports. Similarly, when hills stood in the way, the inhabitants of Seattle washed them down into the sea. On the level stretches thus created were built shops and business establishments.

The city of Seattle was the nearest United States port to the Orient. She was already established as the mart for Alaska commerce. The canal would open up vast intercoastal and South American trade. The wheat-

Now, however, Seattle wanted her harbour and port facilities. In 1907 a bill was introduced in the legislature providing for the formation of port districts in the State. A fighting Welshman by the name of Robert Bridges, backed by a group of public-

The vested interests had lost one fight but were not defeated. The Port of Seattle was organized in 1911 and £1,000,000 in bonds was voted to prepare plans, buy property and build terminals. The Port had the power of eminent domain (sovereign power of control over private property).

Since that time there has been developed on Seattle’s harbour frontage a group of terminal facilities second to none in the world. They have been planned to fit the peculiar needs of North-

The outstanding features of the Port of Seattle’s development are the subsidiary facilities adjacent to the piers and the part these have taken in the development of North-

At Hanford Street terminal is a 1,500,000-

First Experiments in Cold Pack Storage

Smith’s Cove terminals, Piers 40 and 41, claim to be the largest pier-

On the port’s industrial sites have been built machine shops, foundries, and manufacturing plants. In Seattle there are no harbour dues or charges against vessels for the use of terminal facilities. The port piers are reached over common user tracks without shunting charges. All steamship lines and land transportation agencies have equal rights to the use of the port facilities.

The subsidiary facilities have been a means of promoting industries in the North-

The United States Department of Agriculture Bureau of Plant Industry maintains a Frozen Pack Laboratory, the first of its kind in the world, at the Spokane Street terminal.

The fresh fish warehouses have prevented enormous waste of fresh fish and have made it possible for the equitable distribution of this product throughout the year. The Hanford Street elevator changed the method of exporting wheat from sacked to bulk and has made the Pacific North-

S eattle is one of the major ports of the world. Nature provided the wonderful harbour, the salubrious climate, the beautiful lakes and the majestic mountains, but the spirit of her pioneers and the enterprise of her citizens gave Seattle her port, her industries and shipping, her schools, her University and cultural development.

eattle is one of the major ports of the world. Nature provided the wonderful harbour, the salubrious climate, the beautiful lakes and the majestic mountains, but the spirit of her pioneers and the enterprise of her citizens gave Seattle her port, her industries and shipping, her schools, her University and cultural development.

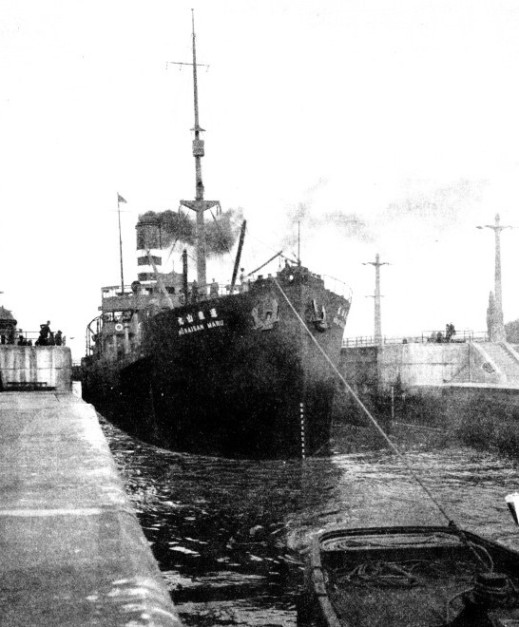

A BIG TRANSPACIFIC FREIGHTER passing through a lock in the Lake Washington Canal. The canal connects Lake Union, in the city of Seattle, with Lake Washington, on its eastern boundary. The Horaisan Maru was a steamer of 6,089 tons gross, built in 1917 in Japan. Her length was 407 ft. 2 in., her beam 50 ft. 9 in. and her depth 32 ft. 6 in.

You can read more on “American Shipping”, “Japanese Shipping” and

“New York -