© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Heroes of the “Trevessa”

When the steamship “Trevessa” sank in the Indian Ocean, her officers and crew sailed over 1,500 miles in open boats, displaying endurance and seamanship that maintained the high traditions of the sea

GREAT VOYAGES IN LITTLE SHIPS -

THE THE ILL-

THE story of the two lifeboats of the steamship Trevessa is one of the grandest in the saga of the sea. The ship foundered in June, 1923, almost in the middle of the Indian Ocean, between Australia and Africa, within two hours of having sent out an SOS. Vessels steamed to her aid, but were unable to find any survivors.

Three weeks passed before news came. Then a cable message from the island of Rodriguez stated that a ship’s lifeboat had reached there with Captain Cecil P. T. Foster and a number of the crew. Another message followed announcing that First Officer James C. Stewart Smith had reached Mauritius, a few hundred miles from Rodriguez, in the second boat.

Of the forty-

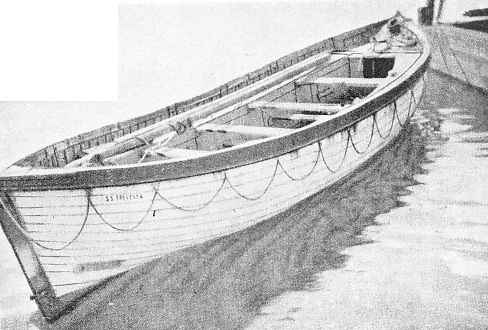

The two boats were of the ordinary pattern built to conform to the regulations of the Board of Trade, their dimensions being: length 26 feet, beam 8 ft 3-

The Trevessa’s lifeboats did not differ from those of the general type. The achievement of the two boats of the Trevessa was, therefore, an outstanding feat of navigation. Yet the men responsible for this feat thought little of it. When the vessel bringing them home was welcomed at Gravesend by sirens and bunting, one remarked: “There must be something up in London to-

Boats little larger than these two have been sailed round the world, but such craft have been equipped and designed for that purpose, whereas ship’s lifeboats are not intended for long voyages. The yachtsman, too, knows what he is contending with and embarks of his own free will, but the able-

It was at first thought that the fate of the Trevessa would remain a mystery comparable to that of the Waratah, the vessel which, lacking wireless equipment, vanished on her maiden voyage. The Trevessa had, however, sent out the news of her plight. Two vessels, the Trevean and the Tregenna, made so thorough a search that the Trevean sighted an oar, which had broken when the captain’s boat was being lowered from the sinking ship, and other wreckage.

The quality of seamanship displayed was of the highest, but the two boats did not set up a record for endurance. Lieutenant William Bligh and his seventeen men were forty-

barren island, and then for fifty-

The Trevessa epic is different. It happened not in the days before wireless telegraphy, nor in time of war, but when every sea-

The steamer Trevessa has sent a wireless message that she is sinking rapidly in the Indian Ocean 1,200 miles from the West Australian coast and that the crew are taking to the boats. The steamer Tregenna, which was 400 miles away, picked up the SOS message and is hastening to her assistance. Owing to the high sea the Tregenna is unable to steer direct and is steaming at only seven knots. -

A message from Lloyd’s Agent at Perth gives the position of the Trevessa as latitude 28 45 S., longitude 85 42 E., and the time of the SOS message as 4 a.m. yesterday. She is a vessel of 5,004 tons gross, was built in 1909, and is owned by Messrs. Edwin Hain and Son., Ltd., St. Ives, who are also the owners of the Tregenna. The Trevessa is on a voyage from Port Pirie to the United Kingdom with a cargo of zinc concentrates and sailed from Fremantle on May 25.

Thus began a drama that ended with Captain Foster and First Officer Smith being received by H. M. King George V at Buckingham Palace. Weeks went by and nothing was found except an upturned boat, a broken oar and wreckage; hope was abandoned. When the news of the survivors came from the Indian Ocean the men were welcomed as though they had returned from the grave.

The story was told by Captain Foster, in 1,700 Miles in Open Boats (Martin Hopkinson, Ltd.), of the loss of the vessel, and of the voyage of the two boats. Inquiries into the loss of the ship were held, first at Mauritius, and then in London. No positive evidence of the cause of the vessel taking in water was obtained. The Court considered that, owing to the nature of the cargo and the severe weather, the ship was subjected to continuous and excessive straining which caused a seam, or seams, to open in the shell-

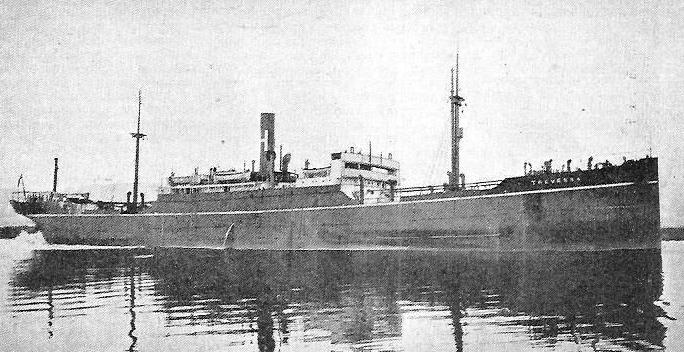

The Trevessa was 401 feet long, 53 feet wide, 28 feet deep, and was built in 1909 at Flensburg, Germany, for a German company, and was interned at Sourabaya, in the Dutch Bast Indies, during the war. Her name was then the Imkenturm. She was taken over by the Shipping Controller and was bought in 1920 by the Hain Steamship Company, of St. Ives, Cornwall. Her speed in smooth water was between ten and eleven knots, and she carried six wooden boats. These were newly installed by the British owners to replace the steel German boats. German owners use steel boats in vessels going into the tropics, the theory being that steel does not contract and open the seams of a boat in the same way as wood. British owners prefer wood, as in an emergency wood can be more easily repaired under abnormal conditions.

The vessel was reconditioned and in January, 1921, was surveyed and classified as A1 100. Shortly before leaving Liverpool on her last voyage she was dry-

The zinc concentrates were stowed in four holds. The cause of the loss of the ship was the entry of water into No. 1 hold. Because of the nature of the cargo and the method of stowing it, the water was prevented from reaching the bilges and tanks, and could not be removed by the pumps. The method of loading was the same as that employed for hundreds of vessels at Port Pirie.

At one of the inquiries it was learned that some of the men were superstitious. A black cat which they had adopted at Port Pirie deserted the ship before she sailed, and, in addition, Captain Foster disposed of two kittens from a batch of six black kittens. He told the more superstitious men that these kittens each had a white patch. Before the ship reached Fremantle a tabby cat died. As she was a particular pet it was believed by some of the crew that luck had left the ship. After coaling at Fremantle, the Trevessa sailed on May 25 for Durban and soon ran into a gale. Bad weather slowed her considerably, but she behaved well. On June 3 a huge sea broke aboard amidships and tore the two port lifeboats from the lashings, breaking the door of the chief engineer’s cabin. Captain Foster eased the speed and turned the ship’s head to the seas while the two boats were secured. The weather became worse and he decided to heave to.

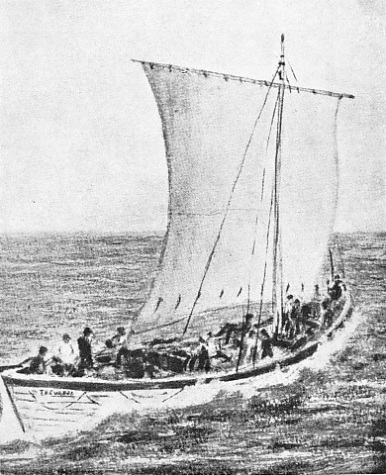

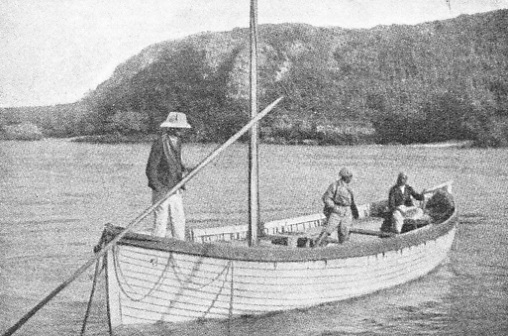

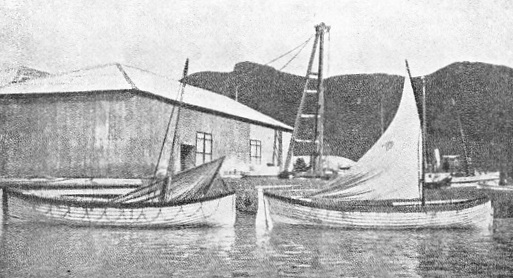

NO. 1 BOAT UNDER SAIL. In the first boat of the Trevessa were the Captain, Cecil P. T. Foster, and nineteen others. In No. 3 Boat there were the remaining twenty-

That midnight Michael Scully, a 62-

Disaster came suddenly. At midnight, from the bridge, everything appeared to be in order. An hour later Captain Foster knew that his ship was doomed, and had ordered the wireless officer to send the SOS, giving the ship’s position, and to signal that they were abandoning her. All the crew were taken off in the two starboard lifeboats, Nos. 1 and 3. At 2.15, when the fore-

The zinc concentrates, being almost impervious to water, had converted each hold into a watertight compartment. Thus the water in No. 1 hold could not escape to the bilges, nor was it possible to ascertain its presence by sounding. Although Captain Foster immediately ordered the pumps to be tried, and these were kept going until the engine-

After they had received the news from A.B. Scully, the captain and the chief engineer went to the forecastle. Such was the noise of the storm that they could not hear anything until they listened with one ear to the deck and heard the swishing of water. The chief engineer and the second engineer went into the forepeak tank, where they found that the bulkhead was beginning to bulge. The bulge was about as big as a dinner plate and water was squirting through a six-

To ease the pressure on the bulkheads, Captain Foster turned the Trevessa round so that she was stern-

While Captain Foster was serving as an officer during the war of 1914-

Abandoning Ship

From this ordeal Captain Foster gained valuable experience of emergency preparations. Chief Steward R. H. James had sailed with Captain Foster since August, 1918, and Captain Foster had in those days gone carefully into the provisioning of lifeboats.

The chief steward and his assistants set to work provisioning the two boats, a task of danger and difficulty. The storeroom was right aft, and the boxes and cases had to be carried up a ladder and a companion way to the poop deck. The stewards had then to run the gauntlet of the heavy seas that were breaking over the after well-

It was a big task. When the required quantity had been brought to the two starboard boats, the chief steward reported to Captain Foster and asked if there was time to get more. But the fore end of the ship was almost under water and the risk was too great. Six cases of milk and twelve tins of biscuits were divided between the two boats, and cartons of cigarettes and tobacco were placed in them. Water, the chart and sextants were put in the boats, lifebelts were issued, and the two lifeboats were swung out ready to be lowered.

It was dark and a heavy sea was running. The stern of the ship was so high out of the water that the rudder was of little use, but the two boats were lowered into the sea without damage or panic. The few men ordered into them fended off from the ship’s side, while the others stood by for the order to enter. When Captain Foster gave the command they got in either by jumping when the boats rose almost level to the ship’s rail on the top of a sea, or by sliding down ropes. Only one man fell into the sea, and he was quickly pulled into a boat. The seas were between twenty and thirty feet high and a wind of over forty and fifty miles an hour was blowing.

The boats remained alongside while the captain collected some of the ship’s papers and other articles. Some of the men did not put on their lifebelts, as they wanted to be free in the work of getting the boats clear of the ship.

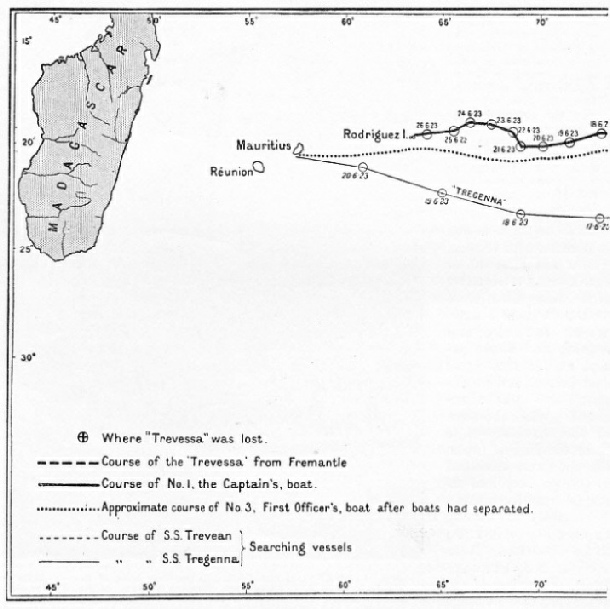

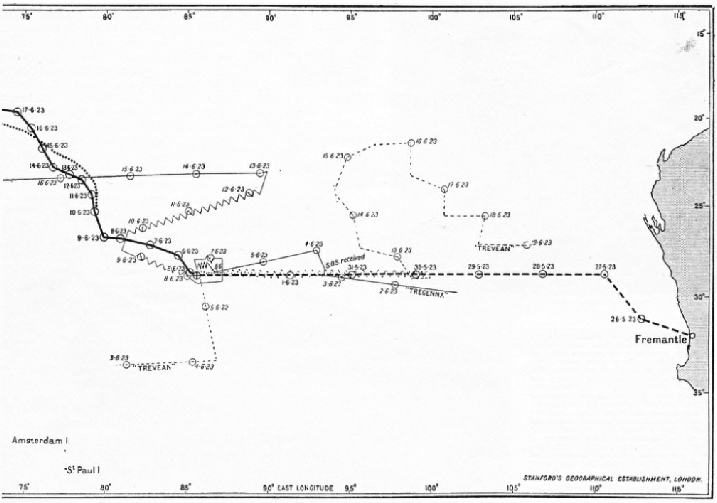

A GALLANT FIGHT FOR LIFE was made by the members of the S.S. Trevessa, and the courses their tiny boats took are shown on these maps. No. 1 Boat travelled 1,556 miles to reach Rodriguez Island, and No. 3 Boat 1,747 miles to Mauritius. No. 1 Boat’s voyage occupied twenty-

A black cat and her four black kittens were placed in the captain’s boat, but the mother jumped back to the ship, and without her it was impossible to keep the kittens.

By the time the forty-

The two boats were in the middle of the Indian Ocean in a gale, over a thousand miles from land. It was not yet three o’clock in the morning of June 4, 1923.

No Rescuers Seen

Twenty men were in No. 1 Boat, including the Captain. There were six Englishmen, two Scotsmen, three Irishmen, two Welshmen, two Burmese, two Arabs, two Portuguese West Africans and one Indian. In the chief officer’s boat, No. 3, there were twenty-

At daylight the two boats came close, and Captain Foster gave orders that they were to drift to sea-

The first day was spent in overhauling gear and estimating the chances of being picked up by one of the vessels which had answered the SOS call. No smoke had been seen by five o’clock in the afternoon, and the boats had drifted north and east of the position where the ship had foundered. Captain Foster decided that delay was dangerous. The chances of being picked up would be as good if the boats sailed to the westward as if they drifted, and the course would be towards Rodriguez and Mauritius.

He made a careful survey of all the stores and water. The water beakers, the tins of biscuits and one case of condensed milk were brought aft in his boat so that he could keep his eyes on them. From first to last he had the entire situation under control. All the stores could not be moved aft, but the screw cap of the biscuit tin left forward was hardened up so that this tin and the cases of condensed milk near the mast could not be tampered with without noise. No attempt was made, but Captain Foster knew by experience the extremities to which men are driven by hunger and thirst.

Directly the order to sail was given the problem arose of keeping the boats in touch. The sail of the captain’s boat was larger than that of the other, but before long the step of the mast gave way and she became the slower boat until the mast was repaired. An attempt at towing was made by the other boat, but the tow-

A close-

The mishap to the step of the mast was remedied by rigging a forestay, by wedging cases of milk on either side to prevent the mast from slipping sideways, and by lashing the foot of the mast. Later two backstays were added.

The stores which the Board of Trade regulations require to be in each boat (one quart of water and two pounds of biscuits for each man) were considerably increased. In the captain’s boat the total quantity of water was about fourteen gallons, and about eight were used on the journey. The biscuits weighed 125 lb, but nearly 50 lb were spoiled by sea-

condensed milk proved invaluable. Captain Foster’s decision to depend on these things and also on water was based on his experiences in an open boat in war time. The condensed milk was assimilated when the men’s mouths were too dry to masticate the hard biscuits, and the cigarettes and tobacco soothed them in their fretful moments and did not increase their thirst.

At dawn on the second day, June 5, Captain Foster decided to take advantage of the existing wind and work north into the region of the south-

The decision to make for Mauritius was reached after a great deal of thought. The ship sank at a position about 1,600 miles from Fremantle and 1,728 away from Mauritius, but an attempt to get back to Australia would have meant fighting an adverse current. Captain Foster hoped to carry the westerly wind across the usual calm belt at that time of the year, and also, because of the season, to encounter rain to augment his water supply. Once in the region of the trade wind the breeze would be favourable to them for sailing towards the island of Mauritius. The chart was in the first officer’s boat with some nautical books and tables, but there was no chronometer to assist in determining the longitude. The movement of the boats rendered the two spirit compasses unreliable, so the men had to steer by the sun and the stars.

WATER RATIONS in the two open boats had to be reduced to the minimum necessary to sustain life. In No. 1 Boat there were only some fourteen gallons of water in the beakers for twenty men during the 1,556 miles voyage to Rodriguez. Rain was caught in an ingenious fashion; the rain was allowed to run down over the face, then down an improvised tin chute held under the chin into a small tin, as illustrated here.

On the third day time was lost, as the mast, halyard and tiller-

In the captain’s boat the rations were issued with care to ensure that every man was satisfied that he was getting his due share. The amount of water allotted was one-

The captain, officers, engineers and the chief steward -

There was only one issue of water -

for water long before the issue was due. The captain disregarded their appeals and made them wait until the hands of his wrist watch pointed to the allotted hour. Two o’clock was the great time of the day. The water brought temporary relief and every man lighted a cigarette or pipe. Then for a while they enjoyed some measure of bodily contentment.

Captain Foster first issued the water at 2 p.m. on June 6. The Trevessa had foundered at 2.45 a.m. on June 4. The weather was cool and the men, being comparatively fresh, did not greatly feel the lack of water. First Officer Smith issued a ration of water on June 5 at noon.

Starvation Diet

The lids of cigarette tins served as plates for the issue of condensed milk. One lid of milk, equal to about four teaspoonfuls, was a ration, and this was issued twice daily, at eight in the morning with a biscuit, and without a biscuit at four in the afternoon.

Because of the lack of water the biscuits were so difficult to swallow that sometimes the men, starving as they were, could not eat them. On some days an extra issue of milk was served at noon and the biscuit ration was increased, but this ration was cut from time to time. Lack of moisture made a biscuit become dry dust in a man’s mouth and he could blow it out of his mouth. Water was too precious to mix with biscuit. Captain Foster tried folding a biscuit in a piece of canvas, pounding it with a boat-

Slowly the days passed, but there was no sign of a ship. The leak in the captain’s boat was caulked and checked, and considerably reduced the labour of baling, but the constant work of shifting sail so that the captain’s boat did not get out of sight of' the first officer’s boat was wearisome.

Captain Foster debated carefully whether it would be wiser for the two boats to continue in company, or whether their chances of rescue would be better if they separated. There was a moral value in company. The men, weak as they were, still had a sense of humour, and the occupants of one boat shouted joking remarks across the sea to those in the other. The fact that the larger sail of the captain’s boat made her faster was always pointed out by those in the chief officer’s boat when they were chaffed for their slow speed.

It became obvious to Captain Foster that the best plan for the two boats would be to separate, as when they were wide apart their chances of being seen by a steamer would be doubled, and if one boat were picked up the men would tell the rescuers of the other.

AT MAURITIUS. No. 3 Boat sighted this island on June 28, 1923, over twenty-

The faster boat would in all probability be the first to reach land, but the slower boat had an equal chance of being picked up by a ship. Either boat would have an approximate idea of the position of the other and, when reaching land, or on being picked up, would be able to give the news of the plight of the other boat.

Although Captain Foster did not know it, the Tregenna, was within 100 miles of the two boats on June 9 when he made his decision. After the boats had drawn together at seven in the morning, he told First Officer Smith that either boat would sail independently. The first officer looked out the declinations of the sun and certain stars from his nautical almanac and gave the figures to the captain. The boats’ crews cheered one another, and the two boats parted, the faster boat drawing ahead and passing out of sight at two in the afternoon. Either boat then had the horizon to itself.

The Tregenna, according to calculations based on the approximate positions of the boats, was comparatively near on several days. On June 7 she was about eighty-

The Tregenna continued in a westerly direction, but south of the boats, and did not cross their tracks again. Another ship, the Trevean, was searching to the east, between the place where the Trevessa had sunk and Australia. The Tregenna, however, came tantalizingly near to success and, but for bad luck, would have picked up one or both of the boats and saved several lives. Neither lifeboat was equipped with wireless.

Water continued to be the dominating obsession of the men in the boats. Every day Captain Foster measured the water in the two beakers as he doled out the meagre allowance. The temptation to appease the men’s sufferings on some days was great, but having been through one ordeal, the captain knew that everything depended upon rigid adherence to the strict rationing. Any outbreak of violence caused by the craving for water would have been disastrous.

Occasionally the men were fortunate -

V arious devices were tried. In rain squalls the men took off their salt-

arious devices were tried. In rain squalls the men took off their salt-

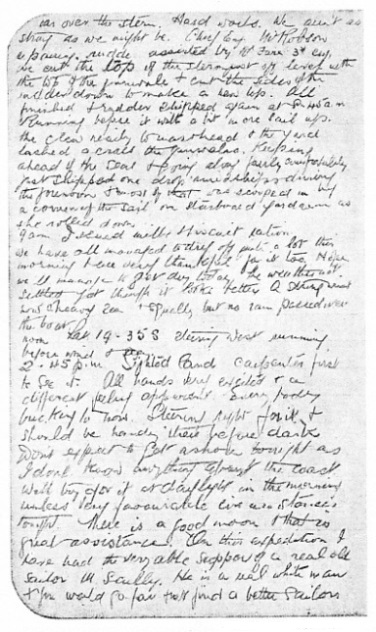

DRAMATIC RECORDS of the men’s existence in the boats after the ship had been abandoned were kept by the captain in No. 1 Boat and by the first officer in No. 3. The captain kept his log until land was reached, but on the twelfth day water came into No. 3 Boat and ruined all the paper on which the first officer could continue his log. This illustration is of a page from the captain's log.

Before long Captain Foster had to decide whether he should break the rule of equal rations for all in the hope of saving the lives of two men who were weakening under the strain. Jacob Ali, an Indian fireman, and, soon after, Mussim Nagi, an Arab fireman, fell ill. Ali was delirious and imagined himself back in the Trevessa; he talked of making tea and coffee in the galley. The captain allowed him and Nagi a little extra water and milk, but he died on the morning of the seventeenth day. The burial rites according to the dead man’s religion were performed by a Burmese fireman, Hassan Khan (called Tom Patchoo by the men).

Mussim Nagi died at 8.30 the next morning, and was buried from the boat at 10.30. His brother, Ali, was there and so distressed that, he would not participate in the burial.

By this time the men had been cramped in the boat for nearly three weeks. During the morning the sheave in the block at the masthead was carried away and the gear had to be repaired. That night several squalls brought plenty of rain. The men not only drank their fill but also they were able to save a little water. Thus heartened, they were able to face the heavy weather of the nineteenth day, when the boat shipped a large amount of water.

The bad weather continued the following day. The men were reduced to the last case of milk, and Captain Foster had to suspend the noon ration of this and reduce the solid food to one biscuit a man per day. In the afternoon the sea was so high that they hove-

On the morning of the twentieth day they tried to make sail, but the sea was too dangerous, and they did not start until late in the afternoon. The captain found that the boat was being driven too far north by the storm. This meant that unless the boat could be worked south she would pass to the north of Rodriguez. Despite the strain on the gear, she was nursed southward; but the storm soaked the men and the cold began to depress them. Midnight on the twenty-

A few days before landing they saw a bo’sun bird and believed they were nearing land; later they saw a number of Mother Carey’s Chickens, birds which are seen in mid-

Instantly the unshaven, sea-

A Fatal Drink

Encouraged by this sign of human habitation, Captain Foster decided to try to land instead of waiting until the morning. Having passed the outer reef, they saw the anchor lights of the Secunder, the Mauritius Government steamer. They passed close to this ship and were seen and hailed.

A fisherman shouted a warning that they were heading for a reef. They furled the sail and waited for the fisherman, who rowed out to them to act as pilot. Before the boat reached the jetty he was shouting the news to people on shore. So weak were the men that they had lost the use of their legs and had to be helped out of the boat.

Meanwhile the first officer’s boat was still battling with the sea, and the crew’s ordeal was not yet over. The casualties were heavier than those in the captain’s boat. Devices for relieving thirst were resorted to according to the instructions Captain Foster had issued to both crews before they separated. The men snuffed sea-

Jimmy Fraser, an Indian fireman, became ill and died on June 17. Two other firemen, Joseph Abrahim and John Ali, disregarded the order forbidding the drinking of sea-

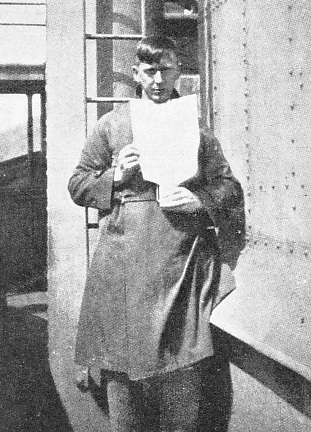

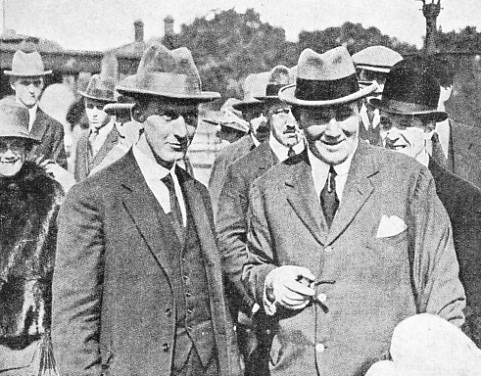

ARRIVAL IN ENGLAND. Captain Cecil Foster (left) and his chief officer photographed at Gravesend in August, 1923, at the end of their amazing adventure. From the island of Mauritius, where the survivors of the two lifeboats eventually met again, they were taken back to England in the R.M.S. Goorkha of the Union Castle Line. An inquiry was held at Mauritius and in London; in each instance the court expressed admiration for the splendid courage and skill displayed by the officers and men of the Trevessa.

An accident caused the death of the second engineer, David Mordecai. He stood up to reach his tin to catch rain-

As the island was sighted the wind became light, and not until the early hours of June 29 did the boat get close to the south coast. Searching in the dark for a landing place, First Officer Smith anchored close to the beach hoping that the surf would moderate and that they would be able to land. But the sea rose suddenly and the anchor cable had to be cut and the boat sailed off the shore. Shortly before dawn they hailed a fishing boat, but the men aboard thought they were ghosts and sailed off. In the morning they saw another boat and hailed her, with better fortune; a fisherman came aboard the lifeboat and piloted it to an anchorage.

Captain Foster reached Rodriguez on the night of June 26, and First Officer Smith reached Mauritius on the morning of June 29. The distance between the two islands is over 300 miles. Directly Captain Foster landed news was sent to Mauritius, and H.M.S. Colombo left that island for Rodriguez, where Captain Foster went aboard and gave the captain of the warship details of the route which First Officer Smith intended to take. The warship then set out in search of Smith’s boat.

On the morning of June 29 the news was cabled from Mauritius that the boat had arrived. H.M.S. Colombo returned to Rodriguez and embarked Captain Foster and his men for Mauritius. On landing at Port Louis, Mauritius, Captain Foster was taken forty miles to where the first-

Discipline and seamanship are two of the outstanding features of this remarkable sea adventure. Despite all temptations, the two crews finished with a reserve of rations, so that had either boat missed the islands, a chance of survival still remained.

The system of doling out the water and food in front of all, so that each man could see that he was receiving his fair share, was the best safeguard against jealousy and suspicion. From the beginning the planning was excellent. Had Captain Foster not taken such care to impress upon Chief Steward James the importance of provisioning the lifeboats for an emergency, and had not the chief steward carried out those orders so exactly, the voyages would not have been possible.

The captain’s decision to sail for the islands instead of drifting for days after the loss of the vessel was in keeping with his character of not relying on chance. The fact that the Trevean sighted the broken oar and other wreckage is no guarantee that the two boats would have been seen had they remained near the spot where the ship was lost. Three boats got away from the steamship Columbian which caught fire in the Atlantic in May, 1914, and separated.

The occupants of one boat saw another boat being picked up, but the rescuing vessel failed to see them. A second boat was picked up later, but the third boat, which was being searched for all the time, was not seen for a fortnight, only four out of fifteen men surviving a fearful ordeal. Captain Foster was not the man to risk the lives of those under him by relying on a chance of being picked up.

Among the men, the personality of Michael Scully stands out. “I have had the very able support of a real old sailor, M. Scully,” wrote Captain Foster. “He is a real white man, and you would go far and not find a better sailor”. Scully was sixty-

The navigation was amazing when it is realized that the boat compasses were useless and that there was no chronometer. The officers, in whom the men had implicit confidence, found their way by the stars.

The fact that seamen of various nationalities had such trust in Captain Foster and First Officer Smith is a tribute to the character of two men whose names will be remembered as long as there is a British Merchant service.

TOGETHER AGAIN. A photograph of the ship’s two boats at Mauritius with the first officer’s on the right. The crew of the captain’s boat (left) were taken to Mauritius by the British warship H.M.S. Colombo, from the island of Rodriguez, where this boat had landed, 344 geographical miles east of Mauritius.

You can read more on “Great Voyages in Little Ships”, “Heroism and Disaster at Sea” and

“Medals for Acts of Bravery” on this website.