© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

From the Aegean to the Black Sea

One of the most important natural waterways in the world is the series of straits dividing Europe from Asia Minor -

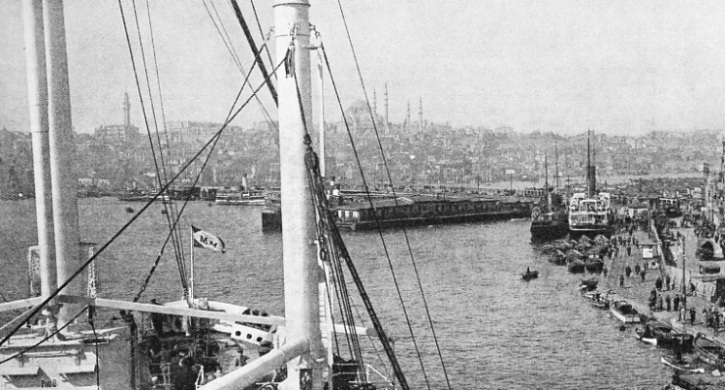

GALATA BRIDGE spans the harbour of Istanbul, which consists of three sections — the Outer Port, Galata Port and the Inner Port. This photograph was taken from the deck of the Champollion, a Messageries Maritimes vessel of 12,546 tons gross. Built in 1924, she has a length of 495 ft. 1 in., a beam of 62 ft. 7 in. and a depth of 40 ft. 6 in. At the quayside on the right is a Turkish vessel of 929 tons gross, the Bursa, built in 1900. She has a length of 210 ft. 7 in., a beam of 30 feet and a moulded depth of 14 feet.

THE Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmara and the Bosporus form the straits linking the Mediterranean with the Black Sea and are the narrow gap in the land bridge that connects Asia Minor with Southern Europe. Constantinople or, to give the city its newest name, Istanbul, is, with its famous harbour of the Golden Horn, the vital port on the waterway. Strategically the waterway ranks after the great canals of the Suez and the Panama and, although it now lags far behind them in commercial importance, it is the key to the Black Sea.

For a long while the Straits, as they are called in European diplomacy, have been one of the thorniest of political problems. British people refer to them as the Dardanelles, although these are only a part of the whole waterway. Unhappily the Straits exacted a heavy toll in lives and suffering during the war of 1914-

At the southern entrance to the Straits, on Gallipoli, are the graves of British soldiers who lost their lives trying to open the Straits to Russian ships. At Scutari, opposite Istanbul, are the graves of British soldiers who died in the Crimean War, which was fought to keep Russian ships out of the Straits.

In 1936 the question of fortifying the Straits and their navigation by warships and commercial vessels was discussed by the Powers concerned. Although the waters and shores of the Straits are Turkish, the Straits are the sole outlet to the Mediterranean for ships from Bulgaria, Romania and the Russian ports on the Black Sea. The shores of the Black Sea are fertile and adjoin one of the richest oilfields in the world.

With more settled conditions the Black Sea could become the collecting pool for argosies of grain and oil, and all the vessels would have to pass through the Straits. The trade in grain and oil is considerable and whether it expands to many times its present dimensions depends upon the political and economic policies of the various countries concerned. Turkey herself is not a great maritime nation. In 1935 there were only 182 vessels, of a total of just under 200,000 tons gross, under the Turkish flag, most of them old craft; but ships of all maritime nations go through the Straits to trade at the Black Sea ports.

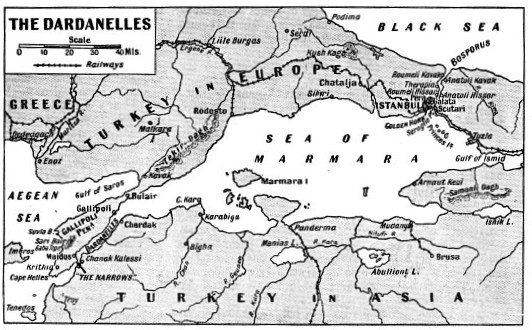

The Straits are about 240 miles long. The Dardanelles, which are entered from the Aegean Sea, are about forty-

At the northern end this sea narrows into the last section of the Straits, called the Bosporus, or Bosphorus, with Istanbul and the Golden Horn on the European shore and Scutari, a suburb of Istanbul, on the Asiatic shore. The Bosporus is about eighteen miles long and only about half a mile wide at one point, with a maximum width of less than three miles. The name means ox-

It may seem strange that the Bosporus is not spanned by a bridge, especially as Xerxes bridged it as far back as 481 B.C. to invade Greece (see the chapter on “The Battle of Salamis”); but the Turk is impelled by an intense nationalism which is antagonistic to internationalism.

Istanbul is no longer the capital of Turkey. The population, according to a recent estimate, is 740,000, whereas that of Ankara or Angora, the capital, is only 123,000 A few years ago the population of Istanbul was estimated to be more than 1,000 000. The trade of the city is in the hands of Greeks. Armenians, Jews and other foreigners.

By sea Istanbul is 3,107 miles from London — almost as far as New York — and the usual route for travellers is overland. Boats are the main means of transport for the thousands of people who have their homes on the lovely shores of the Bosporus outside Istanbul and have business in the city. The deep and spacious harbour of the Golden Horn is an arm of the Bosporus, extending for some four or five miles, and into it flow the streams which the Turks call the Sweet Waters of Europe.

Istanbul, built on the triangular peninsula south of the Golden Horn, is the Turkish city. On the northern side of the harbour are Galata, the business quarter, and Pera, the foreign residential quarter The harbour is spanned by two bridges of boats. The port includes the whole of the Bosporus and the Golden Horn, and is divided into three parts: the Outer Port, Galata Port and the Inner Port. The Outer Port lies beyond Seraglio Point, at the tip of the peninsula. Galata Port is between this point and Galata Bridge. The Inner Port extends from the bridge to the inner end of the Golden Horn.

Link with the Persian Gulf

Galata Quay, 2,480 feet long, is the chief quay, and opposite it is Istanbul Quay 1,240 feet long. On the Asiatic side of the Bosporus there are quays and cranes at Haidar Pasha (Haydar-

There are three graving docks, the largest of which is 510 feet long, and four slipways, the largest of which is available for vessels of up to 176 feet in length. All passengers and goods bound by railway from Asia Minor to Europe, or vice versa, have to be ferried across the Bosporus. Mail steamers link Istanbul with Constanta, the Romanian port on the Black Sea and connect with the route of the Orient Express which traverses Romania, affording an alternative to the Orient Express route from Istanbul through Bulgaria.

Although large passenger liners occasionally visit Istanbul on holiday cruises, the port is no longer the junction of great trade routes. In the harbour, however, are seen cargo vessels from far and near. They have come from or are bound to British ports and ports such as Hamburg, Gothenburg, Rotterdam, Malmo, Rouen, Antwerp and other ports outside the Mediterranean. Some of the vessels come from the Far East via the Suez Canal.

Most of the ships, however, are from the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. They come from Genoa, Venice. Trieste, Alexandria, Cyprus, the Piraeus, Constanta, Braila. Galati, Varna Odessa and Batum. In addition to the ships there are the passenger boats which act as the transport vehicles for the people who live on the shores of the Bosporus, and there is a multitude of small sailing craft and rowing boats.

A VIEW OF THE CROWDED HARBOUR OF ISTANBUL, taken from Galata Bridge. The fairway is shown almost completely congested by lighters of the Port Monopoly. Although the harbour is always crowded with picturesque craft, the extraordinary number present when this photograph was taken was due to an unusual cause. The expiration of a clause in the Treaty of Lausanne gave Turkey the power to revise her customs tariffs. In anticipation of increases Turkish merchants bought goods forward, so overtaxing the customs storage facilities that nearly every available lighter was hired to accommodate the goods awaiting attention. On the hill in the left of the panorama may be seen St. Sophia, one of the most beautiful buildings in the world, and an almost perfect specimen of old Byzantine craftsmanship. The foundation stone was laid in A.D 532 by Emperor Justinian. For over 900 years St Sophia was a Christian church; in 1453 it became a mosque.

The Black Sea which has an area of 164,000 square miles, is remarkable because there is no sign of marine life below a depth of 80 fathoms (480 feet), owing to the amount of sulphuretted hydrogen in the water. Whereas the Mediterranean is saltier than the ocean, the Black Sea is only brackish, because of the huge quantity of fresh water brought down by the great rivers such as the Danube, the Dneister, the Bug, the Dneiper. the Kuban and other streams.

The Black Sea is tideless, but the currents are strong, and it is deep, the maximum depth being over 1,200 fathoms. In winter it is a most unpleasant sheet of water, as the weather is intensely cold and the wind soon sets up a short, choppy sea. The peninsula of the Crimea is, in the summer, the Riviera of Russia, but in winter the climate is bitterly cold. North-

There are numerous ports in various stages of development which send goods through the Straits In Bulgaria there are Burgas and Varna; in Romania Constanta and the Danube port of Sulina with Galati (Galatz) and Braila up the river; in Russia Odessa, Nikolayev, Kherson, Eupatoria, Sevastopol, Tuapse, Poti and Batum; in Turkey, Trebizond and a string of smaller ports along the coast to the Bosporus, some of which are undoubtedly primitive.

As far as the ports on Turkish territory are concerned few developments are expected, but the ports of Odessa and Batum may one day recover their former importance in the exports of grain and petroleum.

Ancient Gates of the Bosporus

The Straits are deep enough for the largest ships, and afford access to this far corner of Europe which taps a region rich in natural resources. As they enter the Bosporus the currents from the Black Sea have considerable force, and before the days of steam were the, cause of many wrecks.

The entrance to the Strait was so dangerous with the wind on shore that its perils became legendary and the ancients said that two rocks came clashing together to destroy ships. The Black Sea pirates used to raid the northern entrance to the Bosporus until the coast was fortified. Inward-

A mole was built out from either shore of the strait in ancient days and a chain was stretched across the channel in time of war. Below this point the Bosporus becomes a marine highway between picturesque shores lined with quays and houses. Freighters of many nations bound to and from Istanbul steam past the passenger boats which are the motor-

BETWEEN EUROPE AND ASIA MINOR lie the Dardanelles, opening out to the Sea of Marmara, and to the Bosporus, which connects the Sea of Marmara with the Black Sea. Istanbul, the ancient city of Constantinople, formerly known as Byzantium, is situated at the southern end of the Bosporus.

Therapia, on the European side, the summer resort of diplomats, means the “Place of Healing”. In the hot summer the cool breeze from the north tempers the heat as the resort lies at a bend of the Bosporus and faces north. A few miles farther the strait becomes constricted at the Narrows, not to be confounded with the Dardanelles Narrows. The Bosporus Narrows are guarded by the forts of Anatoli Hissar and Roumeli Hissar. On either side the houses are so close to deep water that there are instances of buildings having been damaged by steamers or other vessels colliding with them in fog. There is a story of a European house holder of Therapia who saved his home from damage in a fog by banging on a galvanized iron bath on his balcony and thus giving audible warning which enabled the pilot of a fog-

Boatmen listen for the wind in squally weather. If a boatman is smart he will row to the shore and disembark his passengers before the squall has travelled round the bend, reached him, and knocked up a rough sea. Below the Narrows a short distance run by the vessel opens up the sky-

The Dardanelles section of the Strait is as remarkable as the Bosporus section. Gallipoli, the peninsula on the European shore, is fifty-

The greater part of the fighting in the campaign of 1915 took place on the Gallipoli Peninsula. On the Asiatic shore Troy was in ancient days the key to the Straits, and when the Greeks captured it they were able to open the Black Sea to trade and colonization. The Narrows of the Dardanelles are 1,300 yards wide, and the current is strong at this point. Above Chardak the Dardanelles widens out past Cape Kara into the Sea of Marmara, the island from which the sea takes its name being near this entrance.

Eastern Bulwark of Christendom

The first city on the site of Constantinople was called Byzantium, and was founded about 660 B.C. Despite many vicissitudes it became a great port and mart. The Roman Emperor Constantine was so impressed by the site that he decided to rebuild the city and make it the capital of the Roman Empire. The new city was inaugurated in A.D. 330, and although it did not displace Rome it became the capital of the East Roman Empire, the eastern bulwark of Christendom and the seat of the Greek Orthodox Church. Greek influence became paramount, and Constantinople developed into one of the greatest cities in the world and a storehouse of learning after Rome was overthrown. In time of war the Straits were closed to enemy galleys, and the Golden Horn was protected by a chain stretched across the entrance. The city itself was well protected by massive walls.

The produce of Europe came down the Danube and other rivers, and thence by water to the city. The corn of Egypt and the wares and produce of the Mediterranean came up the Dardanelles, and the treasures of the East were ferried across the Bosporus. Despite its splendid natural defences Constantinople was not impregnable. It was attacked time and again by Saracens and Russians, and one siege lasted a year. Constantinople, however, flourished and became the most important commercial city in the world. Then, in 1203, the Crusaders of the fourth Crusade, under Baldwin of Flanders, aided by the galleys of Venice, took the city and sacked it, setting up a Latin empire which lasted for fifty-

Then came a new Power from the East, the Turk. The Turks did not attack Constantinople immediately. They crossed the Dardanelles and occupied Gallipoli about a century before they took Constantinople. They also crossed the Bosporus and built forts on either side, testing the range of their cannon on passing galleys. When they attacked the city they had 300 vessels in their fleet. They evaded the chain across the mouth of the Golden Horn by cutting a dry canal, putting rollers on it and dragging many vessels over the isthmus and into the Golden Horn.

They moved these ships at night, and dawn revealed a disconcerting sight to the warriors on the ramparts of the city. The defenders had become decadent and were no match for the Turks. They even left their posts on the walls to go into the city for their meals.

The rout of the defenders and fall of Constantinople in 1453 is one of the turning points in the story of the world, for it had two great effects. One was that the scholars who fled from the city went to Italy and gave impetus to the Renaissance, which freed men’s minds from the shackles of ignorance. The other was that the sea power of Islam barred the old-

Other corsairs captured Tripoli. Although the connexion between Algiers and Turkey was always slight, the Algerine pirates harassed shipping until the nineteenth century. Egypt passed under Turkish rule, and at one time the entire shores of the Mediterranean, excepting Italy, France and Spain, were nominally Turkish.

The magnificent church of St. Sophia, which was to Orthodox Christians what St. Peter’s was to Roman Catholics, became a mosque, the heart of the city of Constantine became Turkish Istanbul, but the settlements of Galata and Pera were a refuge for merchants of all races and faiths. Greeks, Armenians, Jews driven from Spain by the Christians, and men of many nationalities prospered on the northern shore of the Golden Horn. The Turks manned their galleys with Christian slaves. They took the Christian children from towns they captured, turned them into Moslems, and trained them to be soldiers in the corps of Janissaries, who at one time were the masters of Turkey.

Had the Turks been a seafaring people, possession of Constantinople would have made them a world Power, but they are not mariners or traders, although they are soldiers. At times their occupation of Constantinople has depended upon the jealousy and stupidity of the European Powers.

The development of Russian trade at the Black Sea ports made the Straits an artery of commerce before the war of 1914-

THE QUAYSIDE AT GALATA, in the harbour of Istanbul, has a length of 2,489 feet. The Lloyd Triestino vessel moored to the quay in the centre foreground is the Palestina, a twin-

You can read more on “Battle of the Dardanelles”, “Italian Shipping” and “The Suez Canal” on this website.