© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Italian Shipping

Although the foundations of Italian shipping were laid in the commerce of the Roman Empire and in the medieval prosperity of such cities as Genoa and Venice, the modern Italian merchant fleet is a vigorous product of Government action

SEA TRANSPORT OF THE NATIONS -

COAST QUADRUPLE-

THE Italians have been a maritime people for many centuries, and their Navy and Mercantile Marine are of great importance to-

When the Roman Empire was split into two, the Eastern Empire had little interest in shipping, contenting itself with taking tribute from traders to the limit of its geographical advantages. The various republics, however, into which Italy was later divided carried on the sea traditions of Rome and improved upon them. Many of these republics had little or no seaboard, but contrived to do a considerable trade, although the greater part was naturally done by the cities which were favoured by Nature, conspicuously Venice and Genoa.

Venice, originally a small fishing community seeking refuge from its enemies in the innumerable islands and marshes which surrounded the city, built fighting ships and trained fighting seamen for its own protection. The famous Arsenal at Venice was one of the first completely equipped naval bases in Europe.

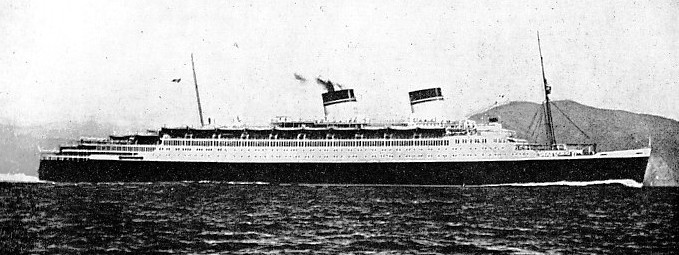

BUILT AT SPEZIA IN 1926, the Giuseppe Mazzini is a twin-screw vessel of 7,453 tons gross, with three decks and a shelter deck. She is registered at Genoa, and has a length of 434 ft 7 in between perpendiculars, a beam of 51 ft 2 in and a depth of 28 ft 1 in. Her steam turbines are connected in pairs by double reduction gearing to her twin shafts. The vessel is owned by Tirrenia Line, comprising the united fleets of the Florio and Citra Lines. She has a speed of 14½ knots.

By the twelfth century the republic was growing powerful and by the thirteenth it was fully developed. The demand for transport to the Crusades gave Venetian seamen a grand opportunity and, although they were accused of wholesale profiteering, the expeditions would have been in sorry plight had it not been for their help. Their galleys penetrated to the farthest corners of Europe where there was promise of trade, but they were always backed by the fighting ships. Venice became the bully of the Mediterranean Sea.

Her rival was Genoa. That city was slower in developing, but when she got into her stride she was even more enterprising than Venice. By the middle of the fifteenth century ships up to 1,500 tons burden are believed to have been built in the city. The shipwrights were capable of turning out, in 1530, the famous Santa Anna for the Knights of Malta, a mighty ship with metal armour and reputed to have been of over 1,700 tons burden. The other Italian cities also had their own merchant services and fleets, notably Naples and Sicily. Even the Papal flag was known and respected at sea. The strength of its shipping and navy varied with the period, but in 1868 it included thirteen ships, of which the flagship was the Papal yacht Immacolata Goncezione, a screw steamer mounting eight guns. When Rome was occupied in 1870 and the Pope withdrew to the Vatican the fleet was dispersed.

As soon as Italy had any pretension to a united government, the shipping industry was recognized as one of the most important in the country. A navy was immediately built up and the disaster of Lissa, in 1866, when the Italian fleet was defeated by the Austrians, inevitable in the circumstances, only proved to the rulers of Italy that sea power was necessary for their existence and prosperity.

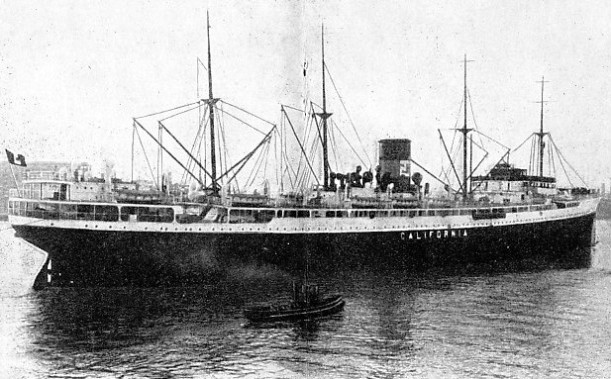

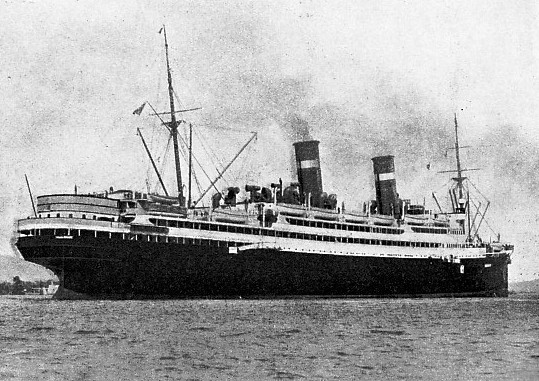

BUILT AS A CUNARD LINER, the Albania was renamed the California by her Italian buyers, Navigazione Libera Triestina. Built at Greenock, Scotland, in 1920, the California is a four-

As soon as Venice was joined to the Kingdom of Italy, this policy was continued with, redoubled energy. English help was sought to design and build the men-

To a people less inclined to maritime enterprise than the Italians, the difficulties would have been insurmountable. They had no coal, nor had they native ore for the building of up-

Their cut prices secured them prosperity in the tramping trade, and their merchants were most enterprising in opening up new markets. Their regular services were mostly subsidized by the Italian Government, not only for the sake of the shipping industry but also to find an outlet for surplus population. Some of the ships for the regular services were specially built, again mostly in Great Britain, but the majority were bought after their foreign owners had reckoned that their life was done.

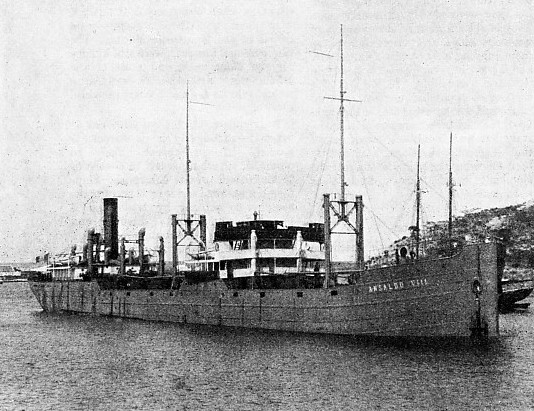

AT CURACAO, DUTCH WEST INDIES, in March 1922, this photograph of the Ansaldo Ottavo - or Ansaldo VIII - was taken. This vessel was renamed the Pellice in November 1934, With a gross tonnage of 5,360, the Pellice has a length of 378 ft 6 in, a beam of 51 ft 6 in and a depth of 28 ft 4 in. Built in 1920 at Sestri Ponenete, she is registered at Genoa. Her oil engines, new in 1928, have a nominal horse-power of 606.

In the subsidy policy which dates from before the creation of United Italy, the authorities always took full cognizance of these foundations of the Merchant Service. While they encouraged the building or buying of new ships they were willing to give generous help to the old ones, provided they could be kept running for the benefit of Italian trade and Italian communications.

Most of the early subsidies were based on the dual fact that the Government was obliged to provide water transport for its citizens before the development of the railways, and that the citizens were obliged to use the water routes in preference to others. From 1862 until 1877, therefore, these subsidies were mostly in the form of generous postal contracts to shipowners who would maintain coastal services. When, however, the railways got into running order about 1877 the coastal contracts were cancelled and the money was devoted to developing foreign trade lines and improving the condition and status of the Merchant Service.

Navigation and Building Bounties

In 1885, when there were a number of overseas mail services running under subsidy, a new system was started which excluded the mail vessels, but which offered a generous navigation bounty for every gross ton per thousand miles steamed or sailed in specified areas. At the same time bounties were also paid on new ships and marine engines built. The rate on iron or steel ships was four times that on those built of wood and on marine engines built. If the ship were suitable for conversion into a fighting ship in time of war — the Italian reserve list was always a considerable one — the scale was still more generous.

As the shipyards developed under this encouragement, duties were increased on shipbuilding materials and more generous bounties were paid on vessels built in Italy. From time to time the system and rates changed. The authorities always cut out unnecessary expense when any particular branch no longer needed encouragement, but they were always willing to put large sums at the disposal of the sections which wanted forcing. There was never any intention to create a boom and the Government did not hesitate to restrict the number of shipbuilders in operation when it was considered that it was more than the country required.

As there was a huge and steadily growing population in a small area, the emigrant ship was an important section of the Merchant Service. As long as the Italian companies could cope with the flow they were generally voluntarily favoured by the settlers, largely on account of the purely Italian routine and victualling that were found in the Italian vessels. The Italians were generally good hard-

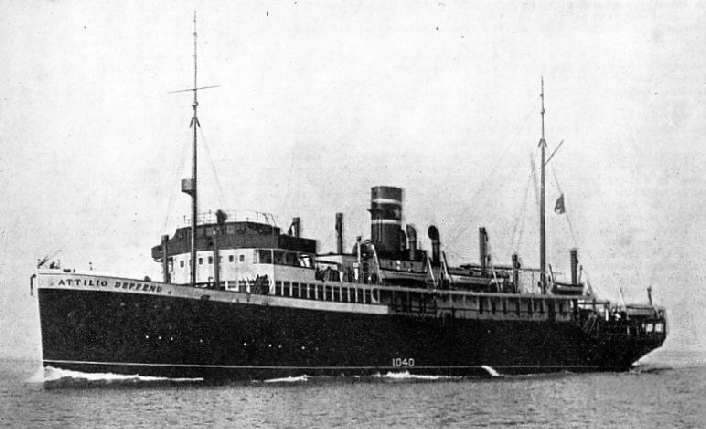

GUN PLATFORMS were placed fore and aft in the Attilio Deffenu, 3,510 tons gross. She is similar in this respect to the majority of the motor ships built by the Fascist regime for Mediterranean services. The Attilio Deffenu, built in 1929 at the Ansaldo works at Sestri Ponente, has a length of 324 feet, a beam of 43 ft. 9 in. and a depth of 21 ft. 5 in. She is registered at Naples.

Against this tendency, which became more marked after the war of 1914-

The Navy, recognized as an absolute necessity for Italy from the early days, was not so easily developed and had to be carefully spoon-

Anticipating the “Dreadnought”

In the ’seventies unarmoured Italian battleships of exceptional speed were carrying the biggest guns to be found in any Navy in the world. Colonel Cuniberti, the Italian naval architect, drew up the designs for all-

The Italian Navy, however, has never quite attained the place to which it has aspired. For many years this was due to Italy being the junior partner in the Triple Alliance, linked to two jealous Powers which checked Italian development whenever possible. Then came the war of 1914-

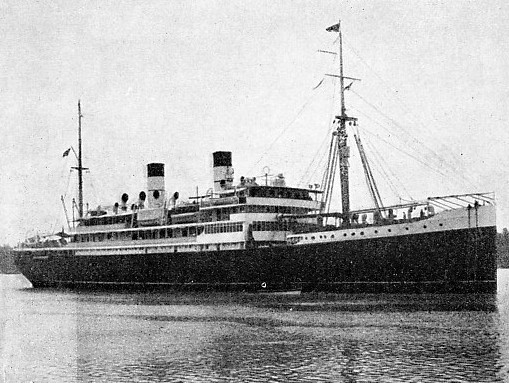

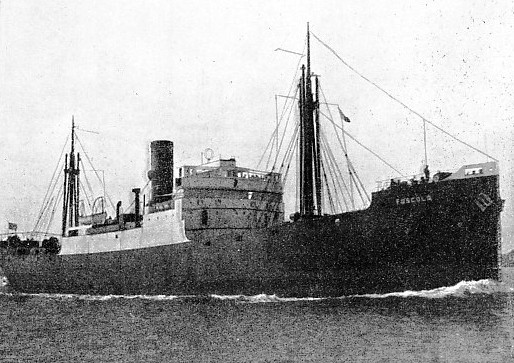

BUILT AT GLASGOW in 1919, the Foscolo has been variously named Maringa and Rogier. A vessel of 3,059 tons gross, the Foscolo belongs to the Adria Line and is registered at Fiume. She has a length of 342 feet, a beam of 46 ft 8 in and a moulded depth of 25 ft 6in. Her triple-expansion engines have a nominal horse-power of 390. The Adria Line maintains services between Italy and other European countries.

The end of the war in 1918 made an immense difference to Italy at sea, for the country acquired the northern Adriatic coast of the former Austro-

Italy did not share in the general distribution of the German Merchant Service in reparation for the submarine campaign. She did far better by taking 213 steamers, totalling nearly 600,000 tons gross, which had formerly been the bulk of the Austro-

In many ways the Fascist regime reversed previous Government policy in dealing with the Merchant Service. It based its first schemes on the fact that shipping should be allowed to work out its own salvation as far as possible, and in the early days shipping was given as much independent control as possible. The subsidy system was entirely overhauled and readjusted.

The Mediterranean services were vastly improved and a large number of ships, nearly all of them handy-

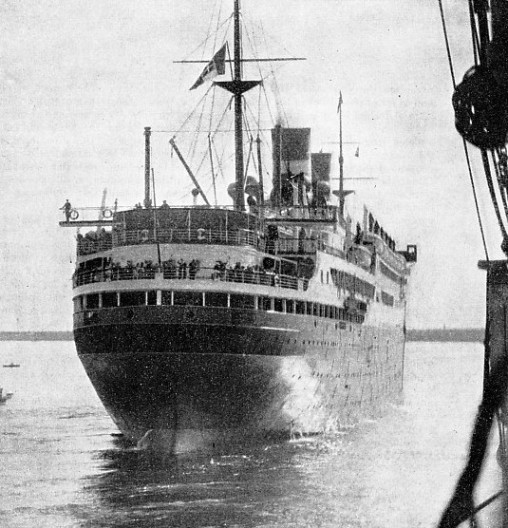

BRITISH-

The subsidized services were divided into two groups, the “indispensable lines” which were those connecting the mainland to the isolated Italian possessions by the shortest route and at the highest speed, and the “useful lines” which connected Italy with foreign ports and were designed to develop trade and emigration. The new subsidy scheme began in 1926, the agreements with the “indispensable lines” being for twenty years and with the “useful lines” for five and ten years. Almost without exception the ships were Italian-

The shipbuilding industry in Italy’ suffered from the slump as much as in other countries. As the Government considered shipbuilding to be as important to the country as shipping, measures were also taken to give it every encouragement. Foreign orders, naval and mercantile, were obtained wherever possible, and in this the whole resources of the Government were mobilized. Shipbuilding bounties were established on a complicated system and a large fund was formed to grant loans to shipowners who would otherwise have been unable to pay for new tonnage.

In 1930 Italian ships were carrying approximately 64 per cent of the country’s overseas commerce, 99 per cent of its coasting trade and nearly all of its domestic passenger business.

At the same time, the Government has not hesitated to abandon ruthlessly any measure which was not fulfilling expectations, and to rebuild and recreate according to the needs of the moment. When the tramp section, which still forms a large part of the Italian Merchant Service, was hard hit, the State established a variable bounty which would give an Italian tramp just enough assistance to permit her to underquote a foreign rival.

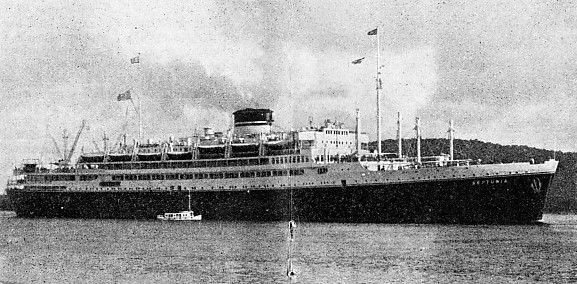

MODERN ITALIAN MOTORSHIP built at Monfalcone, near Trieste, in 1932. The photograph shows the Neptunia, near Santos, Brazil. A quadruple-

The Government offered a large cash prize to any naval architect who would submit so novel a design for a tramp that she would be able to run more economically than the ships of normal design under other flags. The owners of big ships who decided to modernize them found no difficulty in getting the necessary money from the State on easy terms. Considering the advantages, it was regarded as only a minor disadvantage that the State soon put itself into a position to dictate on all mercantile matters, especially on questions of design.

Even without this Government interference the Italian designers were doing well and creating a world-

Atlantic Speed Record

The Augustus had a huge passenger-

Impressions, however, did not satisfy the Italian authorities. They wanted the national flag to have its full place in the sun, and their problem was made more difficult by the indefinite suspension of the emigrant trade to the United States, on which Italian shipping had formerly depended. Undeterred by this suspension, they argued that if they could not get the third-

Germany held the Blue Riband of the Atlantic with the Bremen and the Europa, and most of the American holiday-

The three principal Italian concerns interested in the North and South American trade were the Navigazione Generale Italiana, the Lloyd Sabaudo and the Cosulich Lines. These three companies were in as healthy a competition with one another as keen shipping companies generally are.

The authorities decided to stop this. The Italian Merchant Service was fighting foreign competition and it must do so with a united front. The three companies must sink their differences and run as a single concern. Then the Government would give them every assistance in building ships big and fast enough to gain the Blue Riband for Italy for the first time in its history, and to attract the most fastidious of American travellers.

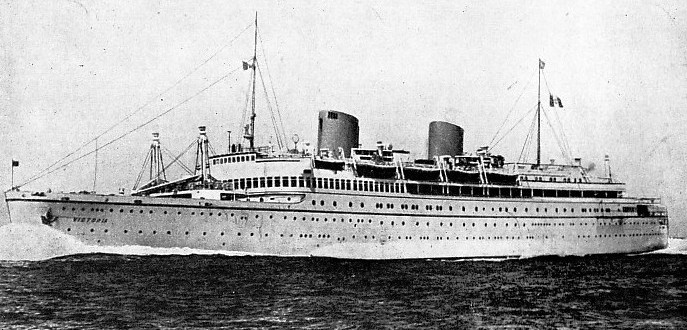

LLOYD TRIESTINO LINER VICTORIA is a quadruple-

So the Italia Line came into being in 1931 as an amalgamation of the three companies. In the following year the Board, which had been formed on the scale usual with such amalgamations, was drastically cut down and seven practical directors took the place of twenty-

The Rex and the Conte di Savoia were built in Italian yards. The vessels had gross tonnages of 51,062 and of 48,502 respectively. Some initial trouble was caused when judgments of experienced shipping men, who were running the company, were overruled. In August 1934, however, the Rex won the Blue Riband in dashing style and, until it was taken from Italy by France with the liner Normandie, the Rex and her sister secured the best of the American holiday traffic. To a country which regards tourists as a major industry, this was all that could be desired.

Similar amalgamations were brought about by State pressure in the other areas. The Lloyd Triestino, for instance, absorbed a number of other concerns and became one of the most important shipping companies in the world. Wherever possible, small local companies also were rationalized and, with the demand for scrap steel flourishing, a large quantity of obsolete and worn-

Small Italian tramp ownerships still exist but not to the extent of only a few years ago. The Italia Line is the most important concern, now embracing the Lloyd Triestino as well as the original companies. It runs services to New York, South America, South Africa, Australia, India and the Far East. Its tonnage will bear comparison with that of any of its rivals, and it has an excellent reputation with passengers.

TWIN-

TWIN-

The Navigazione Libera Triestina runs to South Africa, Central America, West Africa and the North Pacific. The Adria Line maintains many services between Italy and other countries in Europe. The minor companies are kept in a high state of efficiency, perhaps largely by fear of the consequences.

Only a few years ago these minor owners did not enjoy a good reputation, for they were mostly extremely poor. They could afford only the cheapest of worn-

Nothing Left to Chance

It is much easier to do this with the big lines than it is with the little firms which struggle to make a living with one ancient ship that can be kept afloat only with constant hard work. Edicts sweeping such ships away would cause great hardships to owners and to crews, and it was hard for the authorities to find a satisfactory method. Then their plans were facilitated by the steady rise in the price of scrap steel and the small owners were glad enough to rid themselves of their old ships to be replaced by new vessels as the opportunity offered.

The Italo-

Italy aims at the highest efficiency at sea, and — to judge by the improvements recently effected — appears likely to obtain it. Nothing is left to chance or to undirected private enterprise. Shipping is a national service; it permits the country to prosper by trade and it provides employment, directly and indirectly, for the thousands who are no longer able to emigrate as they used to do. Perhaps the most important point of all in the eyes of the authorities is that the personnel, of the Merchant Service is the main support of the rapidly-

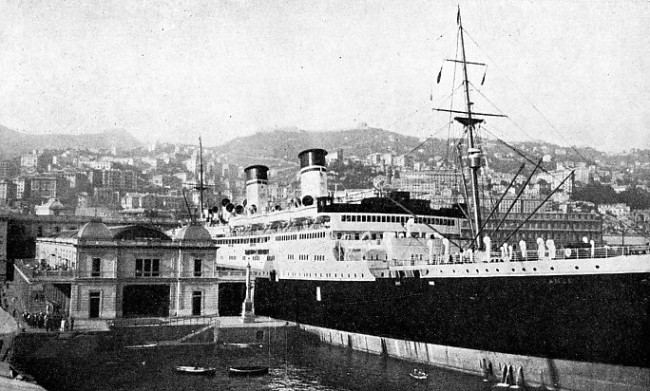

ALONGSIDE THE CUSTOM HOUSE at Genoa, the Conte Grande, of the Italia Line, dominates the scene. She is a twin-

You can read more on “German Shipping”, “The Italian Navy” and “The Rex and the Conte de Savoia” on this website.