© Shipping Wonders of the World 2024 | Contents | Site Map | Contact Us | Cookie Policy

The Cruise of the “Amaryllis”

The circumnavigation of the world, in a 36-

GREAT VOYAGES IN LITTLE SHIPS -

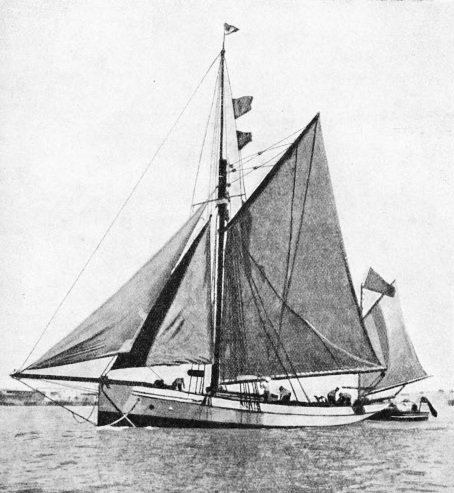

A YAWL OF 36 TONS, Thames measurement, the Amaryllis had a length of 52 feet on the water-

FOR technical efficiency the feat of the late Lieutenant G. H. P. Muhlhauser in sailing the yawl Amaryllis round the world from England with a small crew has not been surpassed. Muhlhauser was a fine seaman and navigator. He served with the Royal Naval Reserve during the war of 1914-

Before the war of 1914-

When he was demobilized in 1919 he got into touch with a yachtsman who was planning a voyage to the West Indies and arranged to go with him in the Amaryllis, which the yachtsman had just bought. She was 36 tons Thames measurement, 62 feet in overall length, 52 feet on the water-

Throughout the voyage Muhlhauser was always bothered by the crew problem and his troubles began before he weighed. He signed on a young fisherman for a voyage to New Zealand and had trouble with the man, and then found that red tape prevented him from discharging the man until he reached New Zealand. Muhlhauser gave the man a month’s wages and thus persuaded him to sign off. Muhlhauser eventually sailed from Plymouth with a crew of three amateurs. Two were brothers and the third was an Irishman. One of the brothers, Charles, was a former lieutenant of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. John, the other, took over the galley and proved a first-

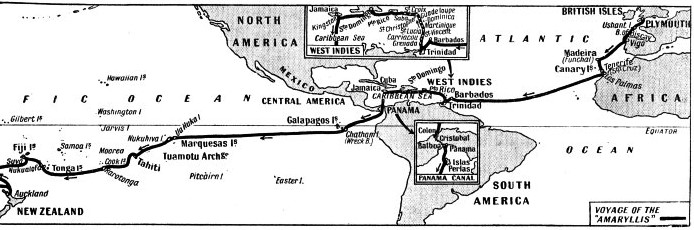

Luckier than most yachts bound across the Bay of Biscay, the Amaryllis had fair weather. Outside Plymouth Breakwater Muhlhauser steered for Ushant, which he gave ample sea room, and then headed for Vigo. By the time this Spanish port was reached the ship’s company had settled down to an ordered routine. Muhlhauser carried three chronometers and adequate charts.

Starting as he did with three amateurs was a risky proceeding, and it says much for his tact that the original ship’s company was a happy one. He was shocked when one man went below during a squall and put on sea-

The first stop after Vigo was Funchal, Madeira, where Muhlhauser had some minor repairs done. At Las Palmas, Canary Islands, David fell sick, and Muhlhauser decided to put in at Santa Cruz, Tenerife, where David recovered.

The Amaryllis reached Barbados in twenty days from Tenerife, and at this place the two brothers left, as they had sailed with the object of finding work in the West Indies. Barbados happened to be prosperous at that time and Muhlhauser had great difficulty in obtaining a crew. He even looked over the local prisoners in his search for two efficient hands. He finally signed on a man as cook and seaman, and secured a lad named Stephane from a Venezuelan schooner. The cook-

From Trinidad Muhlhauser cruised through a good part of the West Indies in search of a reliable hand. He went to Grenada, Carriacou, St. Vincent, St. Lucia, Martinique, Dominica, Guadeloupe, St. Christopher, Saba, St. Croix, Puerto Rico, Santo Domingo and then to Jamaica in search of a hand. The Amaryllis and the Caribbean Sea made this part of the cruise hard work for two men and a lad. Stephane let the yacht gybe and smashed the boom near Jamaica, and when David tried to start the motor they found that a rope had fouled the propeller. David dived with a sharp knife and freed the propeller, and the yacht arrived at Kingston, Jamaica, under trysail and motor.

David’s wife and son were at Kingston, so he said farewell to the Amaryllis, and Muhlhauser was worse off for crew than ever. He managed to find Sam, who had settled in Jamaica, and Sam sailed all the way to New Zealand. He spoke little English, but had some Spanish. The language difficulty was surmounted. When Muhlhauser and Sam failed to understand each other in English, Sam spoke to Stephane in Spanish and Stephane translated Spanish into French.

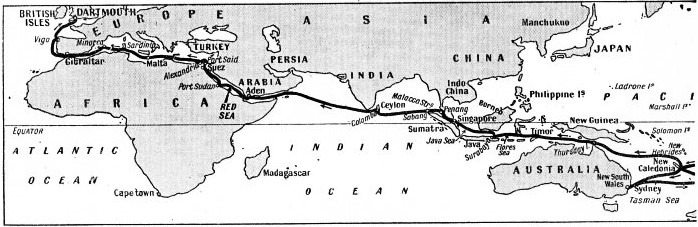

THE ROUTE OF THE AMARYLLIS included many detours. After having reached Barbados in twenty days from Tenerife, Lieutenant Muhlhauser proceeded to Trinidad. He then had to cruise through most of the West Indies in search of a reliable hand. Having passed through the Panama Canal, Muhlhauser had to find another man, and he went to the Islas Perlas in the hope of having the hull cleaned by divers. After a fairly direct voyage to Sydney, he made unsuccessful attempts to sell the yacht, and then sailed to Auckland, still hoping to sell her. At Auckland he picked up a young yachtsman who offered to accompany him to England, and this passage was made by way of Java, Singapore and the Suez Canal. Constant changes in personnel were responsible for many delays, and the whole cruise took Muhlhauser nearly three years.

Before the Amaryllis reached Colon, Muhlhauser appreciated the seamanlikequalities of Sam. Muhlhauser rounded up outside Colon at night in a fresh breeze to heave-

His problems at Balboa, on the Pacific side of the Canal, were to get another man and to clean the hull of the yacht. He nearly lost his coloured crew, as Sam thought the yacht was too small and Stephane did not get on well with Sam. Having failed to find the right type of man, Muhlhauser decided to go to the Islas Perlas, thirty miles from Panama, to get the hull cleaned by divers. The two youths decided to stay with him and he went to the Islas Perlas. He failed to get the hull cleaned as the divers said the water was too cold, and so he set off for the Galapagos. He used the engine during the long calms which are always experienced on this passage to Wreck Bay, Chatham Island.

The condition and colour of the fresh water supplied to the yacht at Wreck Bay looked ominous, but there was nothing better, and Muhlhauser chlorinated it and stored it separately from the other water. Having loaded up with bread, eggs and potatoes, Muhlhauser sailed for the Marquesas.

This part of the cruise, a passage of over 3,000 miles, was sailed in some twenty-

In the Marquesas Muhlhauser anchored for the night off Ua Huka and then went on to Nukuhiva, where the hull was scrubbed by two native divers. Confident in his ability as a navigator Muhlhauser sailed through the dangerous Tuamotu Archipelago instead of going out of his course to avoid it, and he reached Tahiti safely. Having visited Moorea he sailed to Rarotonga, in the Cook Islands, and then to the Tonga Islands. This part of the voyage was stormy. In the Tongas he saw a piano in a boarding house and found that the instrument had once been in the Amaryllis when she was in England.

The piano had been exchanged for one in another yacht and this vessel had been sold in the Tongas. The assumption is that the piano had been taken to the South Seas in Ralph Stock’s Ogre, which was sold at Nukualofa (see the chapter “Adventures of the Dream Ship”). At Suva, Fiji, Muhlhauser waited for an American named Abercrombie, whom he had met in Tahiti, to join him.

On the next passage the Amaryllis was becalmed near a reef and carried on to it by the current before Muhlhauser could start the engine, which was giving trouble. His plight was seen by a lighthouse keeper who arrived with a whaleboat and some natives. They helped to pull the yacht off the reef before much damage was done.

Imperfectly Charted Waters

The yacht was examined in New Caledonia, but the only damage was to three sheets of her copper sheathing. When the Amaryllis arrived at Sydney, New South Wales, Muhlhauser’s friend went ashore and Muhlhauser tried to sell the yacht or to find a sailing partner.

Having failed to do either he sailed to Auckland, New Zealand, still hoping to sell the Amaryllis. The passage across the Tasman Sea was wet and stormy. The yacht had to heave-

Sam decided to go ashore, and Muhlhauser signed him off. In his place Muhlhauser engaged a man called Joe, who proved a valuable acquisition. Muhlhauser decided to sail to England by way of Java, Singapore and the Suez Canal, which meant that part of the course among the islands northeast of Australia would be in imperfectly charted waters. He procured what charts he could, and then sailed. Tadgell was invaluable in dangerous waters. He always went aloft and conned the ship.

Muhlhauser went up to New Caledonia and began threading his way through the islands, having many adventures ashore, and by good seamanship avoiding all misadventures at sea.

FLUSH-

One dark night Muhlhauser had a sudden premonition and altered course. After he had done so he saw an unlighted rock which would have wrecked the Amaryllis had he not changed her course so suddenly. He had been prompted by that super-

Muhlhauser found trouble at Thursday Island when he put the yacht alongside a wharf to scrub her hull, as the tide was strong, and he smashed his topmast when he was bringing the yacht alongside. He sailed to Timor, and went north of this island through the Flores Sea. The engine was taken out and repaired when the yacht was dry-

Proceeding through the Java Sea, north of Java, the Amaryllis put in at Singapore, where Joe signed oft as he wanted to return to New Zealand, and Muhlhauser’s crew troubles began all

over again. He shipped a Belgian who had been in steam but could not master the art of steering a vessel under sail. This man left at the next port, Penang. He was replaced by a Lascar and by a Malay cook. Unfortunately the cook’s religious scruples — he was a Mohammedan — did not allow him to cook bacon, so Stephane had to do that. Having crossed the Straits of Malacca and called at Sabang, Sumatra, the Amaryllis sailed to Colombo. On the passage to Aden Muhlhauser had constantly to watch his two recruits as they were often making mistakes due to inexperience.

Five Weeks to Make 1,300 Miles

The engine, which Muhlhauser had had overhauled, proved invaluable during the tedious passage up the Red Sea. He found that refraction made accurate observation of the sun difficult and he preferred to rely on star sights. The winds were constantly changing, and sails had to be trimmed to get the yacht on her way, as stores were running low. Muhlhauser put in at Port Sudan for stores and water and then went on again, sometimes making only thirty-

When he came to tackle the Suez Canal Muhlhauser found progress slow and had a tug to tow him for most of the way to Port Said, where the Lascar was shipped home. At Alexandria, the

next port, Muhlhauser was to his surprise given a great reception. The yacht went on a slip, and he found that the copper was wearing.

He took on a new hand named Horowitz at Alexandria, but, as the man could not steer a sailing vessel or even row, Muhlhauser sent him ashore at Malta and engaged a man called Galea in his place. Having put in at Sardinia, Minorca and Gibraltar, the Amaryllis entered the Atlantic and coasted north to Vigo, where Muhlhauser had touched on his outward passage. Before she was across the Bay of Biscay Muhlhauser was dreaming of future voyages in his grand little ship. The Amaryllis anchored off Dartmouth and the voyage was over.

In New Zealand Muhlhauser, who did not like the tiller, had it replaced by a steering wheel, which he preferred. This caused trouble when he was in New Zealand waters. The rudder lines jumped off the drum and fouled so that the yacht would have gone on to the rocks had not Muhlhauser cut the lines in time and put the stump of the tiller down by hand.

Muhlhauser’s untimely death, which occurred so soon after the accomplishment of one of the finest voyages of circumnavigation, was a great shock to his many friends in cruising circles. He was a fine type of man, quiet and unassuming, and he got the Amaryllis round the world without any fuss and maintained her in first-

A BROKEN BOOM caused considerable delay when the Amaryllis was approaching Jamaica. This delay was prolonged further by the discovery that a rope had fouled the propeller. One of the crew dived with a sharp knife and freed the propeller, and the yawl arrived at Jamaica under trysail and motor. The auxiliary motor proved invaluable during the later stages of the voyage.

You can read more on “The Adventures of Captain Voss”, “Adventures of the Dream Ship” and “Voyage of the Svaap” on this website.