© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Sydney’s Magnificent Harbour

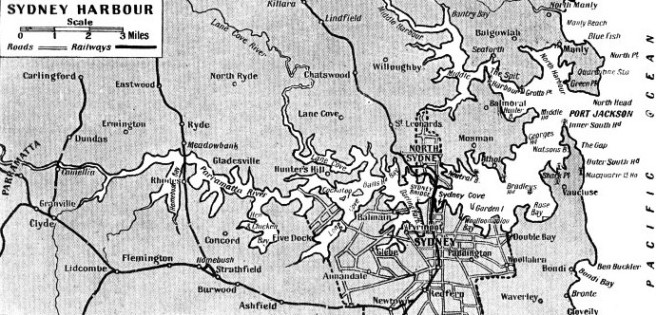

Extending inland for 13 miles, Sydney’s famous harbour claims to be the finest in the world. So broken is the foreshore that the total length of water frontage is 188 miles, which permits of facilities for yachting as well as for commerce

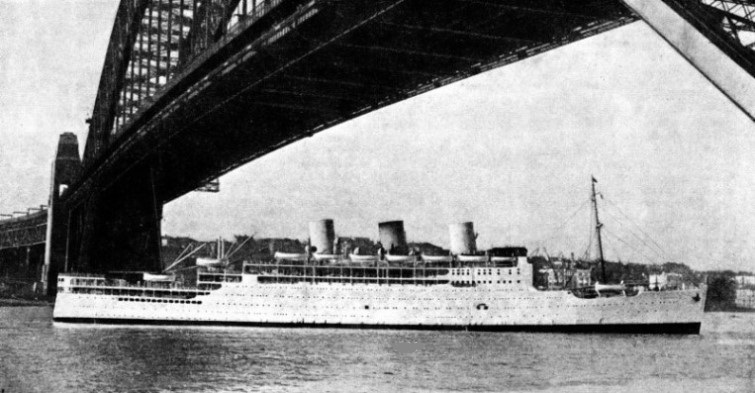

THE GREAT BRIDGE which spans Sydney Harbour was opened in March 1932. Its single span, 1,650 feet long, carries a roadway 57 feet wide, two footways and four lines of railway. A headway of 172 feet is provided at high water. The Manly ferry steamer Dee-

“Port Jackson”, says the Australia Pilot, Vol. III, “independently of being the port of the metropolis of New South Wales, is justly extolled as the most commodious and secure harbour on the east coast of Australia.” There is not one person in Sydney who is not positive that the harbour is the loveliest and the best in the whole world. The magnificent bridge under which pass the liners from all parts of the world is worthy of its superb setting.

To pass between the Heads, which mark the entrance, and to steam into Sydney Harbour early in the morning, when the city is stirring into wakefulness for the day’s work, is an unforgettable experience.

The passenger disembarks in the middle of the bustle of a large city, and the suddenness of the transition from the open sea to the clamour of street traffic is striking. The narrowness of the gap between the Heads, and the height of the headlands, screen the magnitude of the city from seaward, and the abruptness with which the city is revealed as the ship approaches is breath-

The principal passenger liners on the round voyage from London to Australia through the Suez Canal call at the capital ports of all the States in the Commonwealth except Hobart, Tasmania. Although Brisbane, Queensland, is the port where the liners turn round, Sydney is the queen port. None of the other Australian cities which the traveller by sea visits during the long voyage from Tilbury has that blend of ships and streets that distinguishes Sydney from other ports.

The traveller first touches Australian soil at Fremantle, but to see Perth, the capital of Western Australia, he has to travel by train or bus. Similarly, when his ship berths at Port Adelaide he must make a journey to Adelaide, the capital of South Australia. At Melbourne, the magnificent capital city of Victoria, the liner wharves are not in the heart of things. Brisbane, the capital of Queensland, is up the winding Brisbane River, and the wharves are being removed to make way for bridges, and new wharves are being built some distance from the city.

Sydney is the only one of the five principal cities where ships of all sizes, from British liners to trading schooners from the islands of the Pacific, berth in the heart of the city. The harbour is as much a traffic route and a playground for the citizens as are the city streets and the public parks. The famous beaches that front the Pacific provide exhilarating surf-

So multitudinous are the bays, coves, points and peninsulas that it would be tedious to attempt to describe them in detail. The indefatigable Captain Cook saw the opening between the Heads. He did not enter the “small inlet” but named it Port Jackson in honour of the Secretary of the Admiralty and sailed on. Cook was so well satisfied with Botany Bay, which is south of Port Jackson, that when, in 1788, Captain Phillip, who had been appointed Governor and Captain-

At the first sight of the wonderful harbour the disappointment over Botany Bay was immediately forgotten and the vessels moved round to Port Jackson and anchored in Sydney Cove, on the southern shore, just short of where the bridge now spans the harbour. Governor Phillip named the settlement Sydney, after Viscount Sydney, who had suggested the colonization of New South Wales. Circular Quay, at the head of the Cove, became world-

Sydney celebrates January 26 as Anniversary Day, for on that date in 1788 Governor Phillip brought the fleet round from Botany Bay. The subject of transportation is still a tender one with Australians, despite the lapse of time since the system was abolished, but they have no reason to feel deeply about it as the shame of the system lies on Great Britain, not Australia, and many of the victims of it were not criminals. Records found, covering the years from 1832 to 1839, of 217 convict ships which took 22,000 men and 4,000 women to Australia, reveal sentences that were horrible for savagery — seven years’ transportation for stealing a Bible, seven years for stealing a chicken, and similar terms for a nursemaid who stole a comb and for a boy who stole a cheese. Fourteen years was the sentence on a girl aged fourteen who stole a handkerchief with a sixpenny piece tied in a corner of it.

Famous Pilot Steamer

The sufferings of these unhappy victims, herded in iron cages in the convict ships, often ended in death during the long voyage. The owners of the hired transports were paid between £20 and £30 per convict and crammed as many persons on board as they could, with appalling consequences. In 1790, 158 out of 502 persons died in one convict ship, and 95 out of 300 died in another vessel. The system was so awful that the British Government ameliorated the conditions by fitting out ships specially for the purpose and sending convicts twice a year.

Sydney is the birthplace of the whole of modern Australia, and from the harbour sailed the pioneers who founded cities elsewhere in the continent. There was not a building worthy of the name in the whole of Australia before Phillip began the settlement in Sydney Cove. People who point out that the total population of Australia is less than that of London overlook the fact that in the days of sail Australia was many months distant from Great Britain. Before the arrival of the white man the continent was inhabited by a few thousand aboriginals who led an existence so wretched that it is accounted “one of the lowest forms of human life”.

Geologically Sydney Harbour is a “drowned valley” and has no large rivers bringing down silt to form a dangerous bar outside the entrance. The entrance, between the North Head and the South Head is nearly a mile wide and is not less than 80 feet deep, and although it is clearly marked at night by lighthouses, it was the scene of a disastrous wreck in the days of sail. The magnificent British clipper the Dunbar ran bow on into the cliff one night in August 1857. She sank so swiftly that many of her passengers were trapped in their berths and drowned. Only one man, Able Seaman Johnstone, who had been the sole survivor of two other shipwrecks, was saved. The Dunbar was sighted one evening, but in the morning there was no sign of her. Search parties scoured the cliffs and found Johnstone clinging to a ledge of rock where a giant wave had tossed him.

The weather on the night of this wreck was too bad for the pilot boat to go out, but the famous pilot steamer Captain Cook was never once compelled by stress of weather to remain in Port Jackson. She was said to have been the oldest pilot steamer in commission, having been in service for over forty-

THE PRINCIPAL WHARVES of Sydney Harbour are in Woolloomooloo Bay, Sydney Cove, Darling Harbour and Pyrmont. The bridge is some 5 miles distant from the entrance to the harbour at Port Jackson, and connects Sydney with North Sydney. Since the bridge was built passenger traffic handled by ferry boats has been halved, but the ferries are still used to explore the natural beauties of the harbour.

It was decided to replace her in 1936, and to transfer her bronze figurehead of Captain Cook to the new ship. The Captain Cook was built at Mort’s Dock, in the harbour, and was commissioned early in 1894, succeeding a wooden vessel of the same name which was claimed to have been the first steam pilot vessel in the world.

Inside the entrance to Port Jackson, and facing it, is Middle Head, the tip of the peninsula which divides the harbour. The northern arm of the harbour is not commercially important, and Sydney with its wharves and docks is on the southern arm, only about 4 miles from the entrance. Two channels, the Eastern and the Western, have been dredged on either side of the shoal inside the harbour. Either channel has a depth at low water of 40 feet, is 700 feet wide and about half a mile long. As the maximum range of spring tides is only 5 feet, it has not been necessary to build docks with locks, but the steepness of the shores and the depth of water have made shore works costly, and over £12,000,000 has been spent.

In many places the foreshore is so steep that the piles supporting the jetties have to be exceptionally long. In one bay the water is 50 feet deep, and the silt is also deep, necessitating piles 135 feet long. Marine borers feed on the piles and add to maintenance costs. Australians call the teredo, or shipworm, the cobra, and in Sydney Harbour these destructive pests grow to a length of 2 feet and are as thick as a pencil. The gribble, or limnoria, is only about an eighth of an inch long, but about 400 of these tiny creatures have been found in a cubic inch of timber, and they are as destructive as the shipworm. They concentrate on timber exposed by the range of the tide, and an ingenious device has been introduced to check their depredations. A deep collar filled with creosote is placed round the pile, and this rises and falls with the tide and keeps impregnating the pile with creosote.

Area of 22 Square Miles

The harbour extends inland for about 13 miles, and the shore is so indented that the total length of shore line is 188 miles, the total water area being some 22 square miles. Having passed the two dredged channels the vessels have from 40 to 50 feet of water up to the city wharves, depths alongside the wharves ranging up to 40 feet. Practically all the wharves are within a mile of the General Post Office. Including twenty-

The opening of the Sydney Harbour Bridge in 1932 had a tremendous effect on the ferry traffic which is concentrated at the Circular Quay, Sydney Cove. The bridge crosses the harbour from Dawes Point, which is between the Cove and Walsh Bay on the southern shore, to Milsons Point, on the northern shore. To enable large vessels to pass under it, the single span of 1,650 feet, which crosses the harbour, provides a clear height of 172 feet above the water. The immediate effect of the bridge was to halve the volume of passenger traffic handled by the ferries, although this is still large. More than 20,000,000 passengers were carried by ferry steamers in the year ended June 30, 1935, and as the boats perform the services fulfilled by motor-

THERE IS AMPLE HEADROOM under Sydney Harbour Bridge for the P. and O. twin-

Woolloomooloo Bay, where some of the big passenger liners from Great Britain berth, is separated by the Domain, Hyde Park and other open spaces from the heart of the city. Darling Harbour, Pyrmont and Glebe Island are above the bridge, west of Sydney Cove. Farm Cove, which lies between Sydney Cove and Woolloomooloo Bay, is the usual anchorage for visiting warships, and is a beauty spot adjoining the business centre. Sydney is a yachtsman’s paradise. The smooth water of the harbour and the innumerable coves and bays afford wonderful yachting, and the amount of sail carried by the racing yachts is enormous. To prevent the yachts capsizing, the crews act as shifting ballast and lean out to windward, performing acrobatics that give a zest to the racing. Many harbours are muddy and depressing, but that of Sydney is a playground of sparkling blue water with ample room for pleasure as well as for business.

The facilities for repairing and building ships of all types are among the best in the Southern Hemisphere. They comprise graving docks, floating docks, slipways and patent slips. Cockatoo Island, which is m the western part of the harbour, was taken over by the Commonwealth Government in 1913, and is the headquarters of the Cockatoo Docks and Engineering Company, Ltd. Naval and commercial ships are built there. Among the naval vessels built there are the cruisers Brisbane and Adelaide and the destroyer Yarra, which was launched in March 1935. Seaplane carriers, submarines, passenger and cargo vessels, refrigerator ships, sloops, dredgers, colliers, whalers, small oil tankers and light vessels are other types built at Cockatoo Island, and the docking facilities, are capable of accommodating the largest vessels in Australian waters.

The two large graving docks at Cockatoo Island are the Sutherland Dock, the inner caisson of which is 690 feet long, the width being 88 feet, and the Fitzroy Dock, 474 feet long and 50 feet wide. Mort’s Dock, at Mort’s Bay, is 641 feet long and 69 feet wide. The Woolwich Dock, Parramatta River, is 850 feet long and 83 feet wide at the entrance. Two floating docks, respectively 195 feet and 160 feet long, are at Waterview Bay, and a third, 150 feet long, is at Drummoyne. There are three naval slipways, one for cruisers and two for destroyers at Cockatoo Island. The largest patent slip, 270 feet long, is at Mort’s Bay, where there are also two smaller ones. There are two slips at Cockatoo Island and one each at Waterview Bay, Berry’s Bay, Lavender Bay and Goat Island. The most powerful crane is the 150-

The shipping of the port is divided into three classes: overseas (to other countries), interstate (to other States of the Commonwealth), and intrastate (to other ports in New South Wales). The 1,389 overseas ships accounted for 10,767,186 of the total gross tonnage, the 1,139 interstate ships for 3,860,494 tons, and the 4,327 intrastate vessels for 2,958,484 tons. These figures show that Sydney is the port of small ships as well as for the large vessels of the P. and O., the Orient, the Commonwealth and Dominion Lines, and American and Japanese companies.

The navigation laws of the Commonwealth once prohibited vessels not on the Australian register from carrying passengers and cargo between Australian ports, and this policy enabled the Commonwealth to build up a coastal and interstate shipping whose magnitude is shown by the above figures for Sydney. Formerly, if a person wished to travel from Sydney to Fremantle and was not going outside Australian waters he had to travel in an Australian ship and could not book a passage in or send cargo by a British liner bound for Great Britain.

This law was a sore point with British shipowners. The Australian point of view was that they were keeping the coastal trade to their own ships and supporting their own merchant service and that they paid their men higher wages than British and foreign shipowners do. This act, however, is suspended at present and is not likely to be revived. The passenger ships on the interstate service touching at the principal ports from Western Australia to Queensland include some first-

An interesting point about the ships seen in Sydney Harbour is that, although the overseas ships and the interstate vessels either have changed in the last few years to oil fuel for their boilers or are motorships, coal has held its own so far as the coasters of New South Wales are concerned. The coal-

The total trade of Sydney for the year ended June 30, 1935, was 6,601,097 tons, comprising 4,150,119 tons imports and 2,450,978 tons exports. Sydney is the chief wool market and wool exporting centre in the world, 1,147,776 bales being shipped from the port during the year ended June 30, 1935.

In 1936 the Maritime Services Board of New South Wales absorbed the Sydney Harbour Trust, which had administered the harbour since 1901. During the thirty-

Click here to see the photogravure supplement to this chapter.

You can read more on “Australia’s Oldest Steamship”, “Navies of the Dominions” and “Wellington, New Zealand” on this website.