© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Invincible Armada

The defeat of the great Spanish Armada in 1588 probably did more than anything to impress upon England the need for a permanent fleet of fighting ships, and caused a complete revolution in naval strategy and tactics

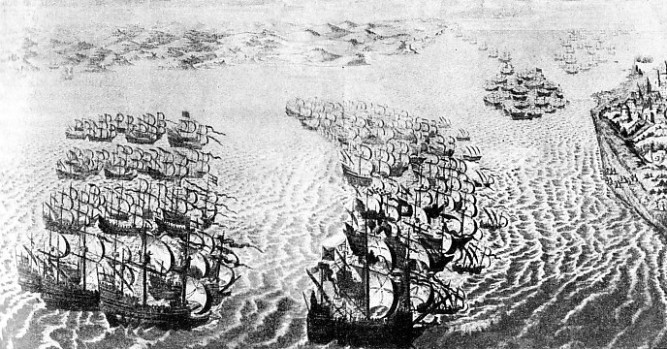

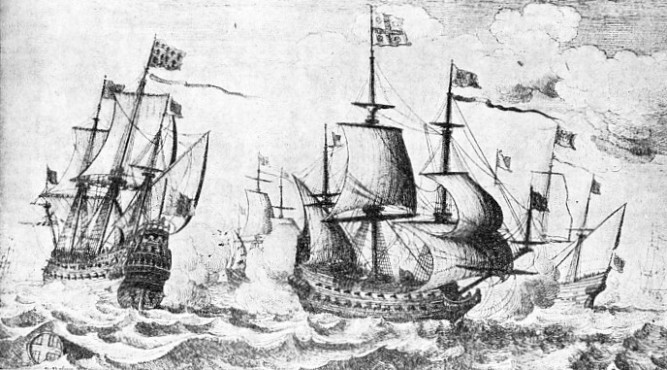

APPROACHING THE FRENCH COAST near Dunkirk, the Spanish Armada was forced into a dangerous position. Its commander, the Duke of Medina Sidonia, had been forced from his anchorage at Calais and was driven past Dunkirk, where the Duke of Parma had been making preparations for the invasion of England. This illustration is taken from tapestries which were destroyed by the fire in the House of Lords in 1834.

IF the battle of Lepanto in 1571 ended the long period when the galley had been the essential type of fighting vessel, the Armada operations in 1588 were to provide the first considerable proof that the sailing-

The full and logical development was not made during Elizabeth’s lifetime, but the basic idea had begun an entirely fresh influence which became more powerful in successive generations when long wars put theories to severe practical test.

The gun obtained the premier consideration. Guns were placed not merely in the bows (as with the Mediterranean galleys), but also along either side of the hull as well as at the stern. The greatest concentration of fire, therefore, came not when the ship was bows-

Just as the battles of Salamis and Lepanto were no sudden events and followed only at the end of preparatory incidents, so the great Armada clash was not an isolated effort but the culmination of many endeavours. In Spain the arts of shipbuilding, shiphandling and navigation had been given a remarkable impetus during the earlier part of the fifteenth century by Henry the Navigator. Without that far-

Southern Europe was comparatively poor, but England was extremely poor. Her trade was indifferent and her need of new foreign markets was considerable. But the Orient, with its spices and rubies, its silks and pepper (much needed for preserving meat), would satisfy all that could be desired; yet these commodities hitherto had come westward to the Mediterranean by land caravans. Thus, when Spain once discovered by seamanship and by the observation of celestial bodies that her ocean-

Henry VIII was not slow to realize that riches could be obtained only by seafaring, yet English seamanhood at that time was numerically small and generally ignorant. Moreover it had not the requisite personnel, apart from the coastal fishermen and the few crews which traded across the North Sea down to the Bay of Biscay, with occasional voyages along the Mediterranean.

Henry therefore introduced a scheme of nautical education at three ports, Deptford-

Little books were published in English during the first half of the sixteenth century, providing information as to havens, roadsteads, soundings, winds, currents and tides. Robert Copland, for example, issued in 1550 a useful “pilot guide” to the English Channel ports, from the Scillies all the way east to the “stryte of Calais”.

Spain, however, besides having her professors of navigation, had also gone beyond mere pilotage when she issued Martin Cortes’ valuable volume on navigation, entitled Breve Compendio. This manual was translated into English by Richard Eden in 1561. He dedicated it to the London City Aldermen (the few English who possessed any wealth) “for the discouery of Landes . . . Unknowen”, and the chapters were to have no little influence on the minds of future maritime explorers.

This Compendio, with all the instruction as to planets, sun, moon, chart-

Thus one successful voyage led to many. The London Aldermen only too gladly subsidized these trading ventures and they provided better ships. A new generation of deep-

Projected Conquest of England

But it is one of the failings of humanity that success breeds jealousy. Apart from the sixteenth-

The remarkable pioneer voyages of Drake, his assault on and destruction of Spanish shipping (especially the treasure vessels), his round-

Already in 1583 Philip of Spain had been urged by his admiral, the Marquess of Santa Cruz, to attempt a conquest of England. Because of the exploits of Elizabeth’s seamen in the West Indies and elsewhere, the suggestion was again put forward during 1586, but in February of that ever memorable 1588 Santa Cruz died. The project, of invading Great Britain by the Armada was not abandoned and a new Commander-

History books have made statements that Philip II was overconfident of victory, and that the galleon was essentially a Spanish type of ship; but to-

As we learn from Richard Hawkyns, the mariner on board a Spanish ship was a kind of dog’s body which anyone could kick. Not those who handled the sails and ropes were esteemed, but rather the soldiers and gunners. Such an attitude possibly derived from that which obtained towards the galleys’ oarsmen.

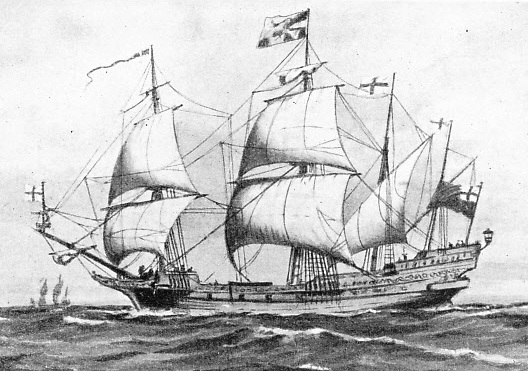

BUILT FOR SIR WALTER RALEGH in 1587, the Anna Royal was bought while still on the stocks by Queen Elizabeth for £5,000. The vessel was renamed Ark Royal, and was the flagship of Lord Howard of Effingham the Spanish Armada. She was one of the largest ships in the English fleet and was of 800 tons burden.

The galleon had been introduced to English service by Henry VIII long before Spain built such a class of vessel. The Spaniards were the last great maritime people to adopt the galleon. This type of vessel had evolved from the trading carracks which used to sail from London and Flanders to the Mediterranean. Rigged with three masts, and with squaresails on foremast and mainmast, the galleon set the typical southern lateen sail on the mizen, because this triangular fore-

The galleon was the battleship’s prototype and the galleass that of the modern armoured cruiser. The galleass in many features resembled the galleon, but had greater length in proportion to beam and largely relied on oars. Thus she was to have greater speed, without sacrificing her fighting ability.

It is an erroneous idea, too long promulgated, that the English ships were all small and that the Spanish ships were large. It is, however, an historical fact that at least seven of the ablest English vessels were of 600 to 1,100 tons, that in the whole Armada only four units were bigger than the 1,100-

The massive Ark Royal, which had been built in 1587 for Sir Walter Ralegh, was sold while still on the stocks to Queen Elizabeth for £5,000. The Ark Royal was of 800 tons and served against the Armada as Lord Howard of Effingham’s flagship. Another four-

The Triumph carried a battery of thirty-

The Spaniards therefore had to import Flemings and other foreigners as gunners. The soldiers had nothing to do until ordered in action to board the enemy, save cleaning the arms, “wherein,” related Richard Hawkyns, “they are not over curious”. Another contemporary, Sir William Monson, has left us with a hint as to the filthy state in which Spanish ships were kept. He says they were “like hogsties and sheep-

Elizabethan men-

No Food and No Pay

Equally were they stinted of victuals by their sovereign. It was expected that the Armada would leave for the English Channel about May 15, 1588, but, instead of the English fleet being well provisioned long before that time, Howard wrote on April 8 to Burghley complaining that they had victuals to last only till May 18, and even then that it would take from four to ten days getting them on board.

Such lack of consideration on the part of those in authority seems scarcely credible when we think of the extreme efficiency in the modern administration of the Royal Navy to-

Lords, our victuals are not yet come ... our extremity will be very great, for our victuals ended the 15th of this month”. Truly those who risked their lives afloat have until recently been indifferently treated, and another of Elizabeth’s naval officers was compelled to protest that the men had long been without their wages.

Despite all these infuriating conditions the much-

In those days no State pensions awaited them, as after the war of 1914-

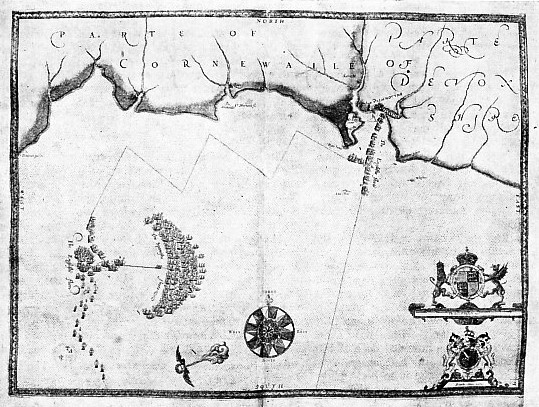

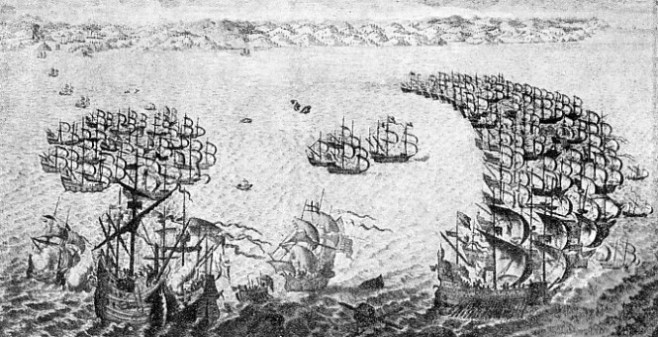

POSITION OF THE ARMADA on Sunday, July 21 1588, off Rame Head, Plymouth Sound. This contemporary print, engraved by Robert Adams, shows Lord Howard’s fleet standing out from Plymouth on the starboard tack to leeward of and across the Armada’s bows. The Spanish ships were pursued down the English Channel in an arc formation by Drake’s fleet, which had tacked down the Cornish coast and advanced to windward of the Armada’s rear. From the first the English showed themselves the better tacticians.

These, then, were the conditions in which ship life was endured in the summer when the whole future of England hung in suspense. “Now are we come,” wrote William Camden, the Elizabethan historian, “to the yeare of Christ one thousand five hundred eighty and eight, which an Astronomer of Konigsberg about an hundred yeares before foretold would be an admirable yeare.

“The rumours of warres, which before were but slight, began now to increase every day more and more ; and now not by uncertaine fame, but by lowd and joynt voyce of all men it was noysed abroad that a most invincible Armada was rigged and prepared in Spaine against England, and that the famousest Captaines and expertest leaders and old souldiers were sent for out of Italy, Sicily, yea and out of America into Spaine.”

It was well known in England from merchants travelling abroad and from seamen in trading ships no less than from information obtained by spies, that during the winter and spring the Spaniards had resumed the invasion preparations which Drake’s attack on Cadiz had halted. But not even Howard knew the intended date of the Armada’s arrival in English waters. Although he expected it to be in May, his reckoning was wrong by two months and more.

Spain, just slowly emerging from the galley age, had establishments for galleys at Seville and Barcelona, but no naval dockyards. Her Armada numbered 130 sail, which included only twenty-

Plan of Invasion

The 130 units comprised Spanish, Portuguese and Italian vessels. Philip appointed over them as Commander-

Medina had to comply with the royal wishes, however, and Drake was not far wrong in suggesting to Walsyngham that he doubted not before long the Duke would indeed “wish himself at St. Mary Port among his orange trees”. The Pope was a true prophet in remarking, “We regret to say it, but we have a poor opinion of this Spanish Armada, and fear some disaster”.

It was not going to be another Lepanto for the Spaniards. As the time drew near, Philip realized this, too, and on April 1 warned Medina that the English would endeavour to fight at long distance, because of their superiority in artillery. “The aim of our men,” he said, “must be to bring him [the enemy] to close quarters and grapple with him”.

Santa Cruz’s plan had been to seize Plymouth, or the Isle of Wight, on his way up the English Channel. Such a scheme was still advocated by Medina’s officers, but Philip was against it. He particularly stressed upon the Duke that he was not to seek a battle, and that if he should happen to fall in with Drake he must avoid the Englishman who had shown himself such a terror to the Spaniards in the New World as well as in the Old.

The Armada’s objective was not to fight on sea but to invade England. Having reached the North Foreland, the fleet was to anchor there and get in touch with the Duke of Parma. Parma was in the Low Countries and would bring his army across from Dunkirk, make a landing on the Kentish shore and join forces with Medina, so that, having conquered England, they might next invade Ireland.

To this end Parma had been for some time busy sending to Italy for shipbuilders and pilots, dredging channels across the Flemish shoals and collecting barges and transports. This strategy, however, was based on the stupid assumption that an army can pass over sea and land on another nation’s shores while that country still has a fleet in being and undefeated. The idea of the Armada being allowed to sail the entire length of the English Channel without being brought to action is so preposterous that we marvel at Philip’s unimaginative mind.

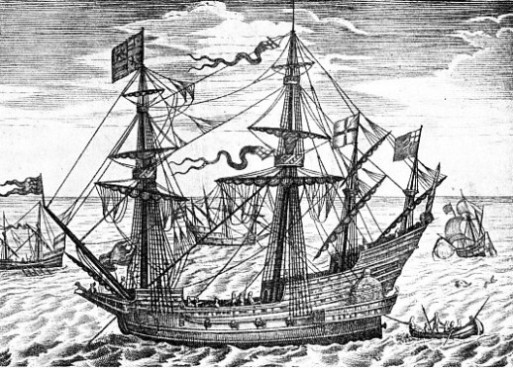

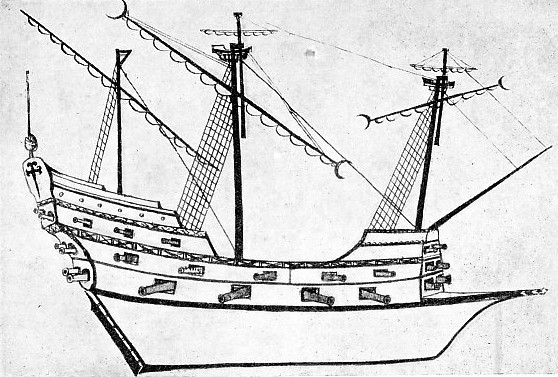

ENGLISH MAN-

The English fleet had been awaiting this event for months. However badly fed and badly paid crews may have been in the past, they were always prepared to suffer bad food, bad pay and privation when fired with ardour to protect their native country. The Armada consisted of sixty-

Originally 9,000 seamen and 17,000 soldiers set forth, or a total of 26,000, yet 24,000 may be regarded as the maximum that ever sighted Devonshire. The galleasses each needed 300 slaves as oarsmen, though sails were used when the wind came fair. The galleasses were low in the waist with square forecastle and high poop, but less towering than a galleon though carrying fifty guns. In some instances a galleass was flush-

The extraordinary variety of guns carried in these rival fleets would surprise a modern naval crew. Homogeneity did not exist. The Triumph, for instance, carried nine demi-

A Total of 2,500 Guns

The long guns were placed right aft through the stern, lest otherwise they might blow up the counter. The shorter guns were placed in the ship’s side for lightness and to ease the ship; but when she heeled over to a smart breeze these had to be taken in and the ports shut to keep out the water. Altogether the Armada carried 2,500 guns of various sorts and sizes.

Although an enormous amount of detailed preparation was made to fit out this Spanish expedition, to divide it into six squadrons, each under a vice-

The Armada assembled in that wide anchorage of the River Tagus which faces the principal square of Lisbon. No more convenient bight than this could have been chosen. It was close to the shore, yet it afforded ample space for unhandy galleons and galleasses in the strong tideway. The sight of this highly beflagged fleet must have been singularly impressive under the brilliant sunshine. On May 14 Medina’s ships dropped down with the tide a little farther towards the mouth and brought up in Belem Bay, where the sixteenth century fortress and the monastery commemorating Vasco da Gama’s discovery of a new sea-

Here the fleet anchored and waited a fortnight, hoping to get a fair wind. Sixteenth-

ELIZABETHAN GALLEONS in use at the time of the Spanish Armada. Some authorities have stated that the galleon was essentially a Spanish type of ship, but the type was introduced to English service by Henry VIII long before it appeared in Spain. The Spaniards were the last great maritime people to adopt the galleon.

On May 28 anchors were hauled up and the Armada got out of the river, but the breeze came from the north, as it frequently does off the Iberian coast, so that mariners have long known it as the “Portuguese trade wind”. The high-

But Medina’s unhappy mind was made no easier when his fleet drifted 100 miles to leeward. The welcome southwester did not blow until June 10, when the ships headed on their course at last; but more trouble soon followed. The ships’ drinking water, which had been lying for four months in the casks, leaked, and the remainder went bad. With this, the putrid meat and the maggoty bread, the men became seriously afflicted, and 500 were rendered unfit for duty.

On June 19, when the ships were off the rock-

But this was not to be. At length, repairs had been completed. The ships had been laid ashore for the underwater portions of the hull to be scrubbed and tallowed. They had been filled up with fresh water and food and the deserters had been replaced by local men.

Arrival in English Channel

The Armada set off on Friday, July 12, with a southerly wind to cross the Bay of Biscay. The speed averaged 6 knots, and by the Monday evening the ships were off the entrance to the English Channel.

Here, as often happens, especially in the month of July, the weather shifted. On the Tuesday a light northerly air with showers blew, but next day the wind backed to west and blew a gale. The bigger ships hove-

Not until the next Friday, July 19, was the fleet in fighting order. The Duke arranged it into three divisions, the general formation being that of an oblique crescent with horns at either end, and himself in the centre. It was thus the same traditional line-

The ships now fixed their position by taking soundings and observation of the sun, so that at 4 o’clock that afternoon the Lizard was sighted, distant nine miles. Stretched out in a concave line, extending seven miles, the “invincible” Armada came sweeping along past the Cornish coast, and this same evening Medina sent his two fly-

With sheets eased and sails bellying, the fleet of invaders ran before the wind majestically rather than speedily. At 1 a.m. on Sunday they fell in with four Falmouth fishermen. From them it was learned that Drake and Howard were already aware of the Armada’s approach, that the English ships on Friday evening had warped out of Plymouth Catwater, and that on Saturday they had sailed from the Sound into the English Channel looking for the enemy.

At 3 p.m. of that day (July 20) English ships sighted the enemy in the distance. Next day “we had them in chase”, wrote Drake to Lord Henry Seymour, “and so coming up to them there hath passed some common shot between some of our fleet and some of theirs . . . the fleet of Spaniards is somewhat about a hundred sails; many great ships, but truly I think not half of them men-

Lord Henry Seymour had been ordered by Elizabeth “to lye upon the coast of the Low Countries with forty shippes, English and Netherlandish, and to watch that the Prince of Parma might not come forth with his forces”. Charles Howard of Effingham, Lord Admiral of England, had been sent to the west of England with Drake as his Vice-

THE ENGAGEMENT OFF PORTLAND on July 23, 1588, is depicted in this illustration from an engraving by A Ryther. During the two preceding days the English fleet had been pursuing the Spanish Armada up the English Channel from Plymouth. The battle off Portland, Dorset, was, however, still indecisive In the foreground of this illustration a large Spanish galleon is firing on an English vessel, and in the background are shown the beacons which gave warning of the Armada’s approach.

As to the number of ships in the English fleet, the contemporary accounts (in accordance with the somewhat inaccurate Tudor arithmetic) differ, but it was approximately 158 — thirty-

While this shows how representative was the aid from English ports, and how readily the Merchant Navy could be added to the Royal Navy, we must not distort the truth. Among the erroneous claims in many school histories has been this: that the English fleet won the campaign because of its many nimble auxiliaries.

That this statement is not true may be at once realized from the following contemporary statement dated August 1, 1588, when Wynter wrote to Walsyngham: “I dare assure your Honour if you had seen that which I have seen, of the simple service that hath been done by the merchant and coast ships, you would have said that we had been little holpen by them, otherwise than that they did make a show”. This is exactly what we should have expected; the main stress of the fighting was borne by the royal fighting ships with their superior armament, while the auxiliaries swelled the numbers to an imposing extent.

From evidence of Dutch seamen who served in the Armada we know that the English ships sailed better than those of the Armada; that the wind up-

Not until 5 a.m. of Sunday, July 21, did the Armada approach Rame Head, Plymouth Sound. Three miles to leeward, off the island of Mewstone, they sighted eleven of the Queen’s ships under Howard manoeuvring to get the weather gauge. Between the Armada and the land were counted forty more ships under Drake. Robert Adam’s contemporary print gives a composite view of the situation covering a period of time rather than any precise minute.

Battle off the Isle of Wight

In this interesting print Howard’s ships are seen standing out to sea on the starboard tack, to leeward of and across the Armada’s bows. Drake’s ships will be noticed making short tacks along the Cornish shore, past Whitsand Bay and Looe, then bearing away and advancing to windward of the enemy’s rear. Howard, after having stood out to sea, bore up and got the enemy’s weather gauge likewise.

Thus from the first the English showed themselves superior tacticians, and were in a position to choose their range. At the outset they had outwitted Medina. So a running fight began and continued till July 22 as the rivals still sped up-

Two days later a fierce battle took place off the Isle of Wight, and on July 27 the Armada had carried out its first, instructions. In reaching Calais Roads it had thus gained a position for awaiting Parma’s arrival from Dunkirk. But now the entire English fleet was concentrated, and the climax was approaching.

Up till now there had been a week of indecisive fighting, which is certainly open to criticism. An early result might have been expected had Howard and Drake in company, sailing in line-

SPANISH TREASURE FRIGATE of Elizabethan times. This unique contemporary picture is taken from the original drawing by an English spy. The vessel appears to be similar to the English man-

From contemporary letters we can fill in details of that eventful week, though its proceedings seem singularly leisurely to modern minds. Sir John Hawkyns, who was on board the Victory, wrote, “We met with this fleet somewhat to the westward of Plymouth upon Sunday in the morning, where we had some small fight with them in the afternoon”. He wrote that a great Biscayan ship after collision lost her foremast and bowsprit, so that Medina left her and Drake captured her.

Another Biscayan was seriously damaged by a barrel of powder getting on fire. She, too, was abandoned and captured by Lord Howard. Drake’s guns had been so busy that by Tuesday he had run short of ammunition; but fortunately the first Biscayan mentioned by Hawkyns was the 1,200-

Off Portland the wind veered from south-

Medina, after all his tribulations and anxieties, anchored in the strong tideway off Calais — no pleasant spot if the wind should come northerly, with the treacherous sands around him. Parma was too frightened by the presence of Dutch and Zealandish ships to make the rendezvous; nor indeed had he embarked his men, who presently deserted. Seymour, who had been waiting with thirty ships to guard the Thames estuary, now joined Howard’s fleet and anchored off Calais close to the Armada. The next duty was to drive the enemy from its anchorage. Howard therefore selected eight of his least valuable units and filled these ships with powder, pitch and brimstone. On the night of Sunday, July 28 — wind and tide being in the same direction — he sent the fire-

Final Victory Off Gravelines

Howard’s fleet pursued the fugitives, and on July 29, off Gravelines, gave them such gunnery that the Armada was driven past Dunkirk. Some of the enemy’s ships were sunk, some abandoned, and others were wrecked at Blankenberghe. Lest Parma should come out, Seymour was sent with the Dutch contingent to watch the Flemish coast. Medina’s fleet sped off up the North Sea utterly routed, and was chased up to the latitude of Aberdeen when the English were compelled by want of provisions and powder to put about and make for Harwich. The Gravelines fight, lasting from 9 a.m. till 6 p.m., was the contest which finally settled the whole issue and gave victory to the English fleet. Drake wrote that nothing had pleased him better “than seeing the enemy flying with a southerly wind to the northward”.

Thus scattered and battered, greatly needing fresh drinking water, most of the enemy’s fleet which had not been sunk or rendered unseaworthy managed to sail round the north of Scotland and down the west coast of Ireland towards the Bay of Biscay. A south-

Of the 130 vessels that left Lisbon in May there came back only fifty-

For England the Armada operations decided that she should continue to enjoy her freedom without Spanish domination. It is true that Spain’s fleet was crippled but not destroyed; yet the victory gave the English nation such a profound confidence in its future as a great maritime Power that a new era dawned in that year. The growth of discovery, overseas trading, the founding of colonies and the inauguration of the East India Company followed as a logical result.

PURSUED UP THE ENGLISH CHANNEL, the Spanish Armada was unable to retaliate for the loss of one of her giant ships. The Nuestra Senora del Rosario, under the command of Don Pedro de Valdez, lost her topmast and was captured by Sir Francis Drake in the Revenge. The two ships may be seen on the left of this illustration.

You can read more on “Drake and the Golden Hind”, “First Voyage Round the World” and

“From Tudor to Victorian Times” on this website.