© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Atlantic Coast of Adventure

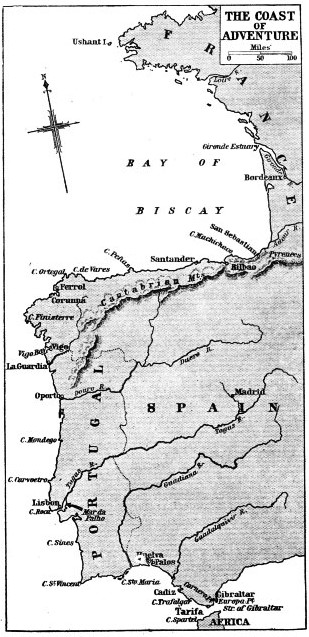

Including the dreaded Bay of Biscay, the Atlantic coast-

IN THE GIRONDE ESTUARY, opening into the Bay of Biscay. Above is the Mole du Verdon, where passengers for Bordeaux, about sixty miles up the estuary, sometimes disembark, although large vessels can reach Bordeaux. The Gironde, formed by the confluence of the Garonne and the Dordogne, is some fifty miles long and from two to six miles wide. The Champlain (above) is a twin-

THE Atlantic coast of Europe, from the island of Ushant to the Strait of Gibraltar, was the starting-

Nowadays the Bay of Biscay is to many people an unpleasant episode between two lighthouses, Ushant and Finisterre. When, however, passengers regain their sealegs they are able to watch the wonderful panorama of the rugged coast-

In many places this great change in the bed of the ocean occurs in a short distance. Hidden by the surface water is a submarine range of mountains as high above the bed of the Atlantic as the Alps are above the sea. When gales blow in from the Atlantic the seas above the vast sunken range, pile up in confused pyramids and do not run true, but become dangerous. When the storms subside, strong and uncertain currents confuse the mariner, and in foggy weather many vessels have been carried off their courses and wrecked.

So crowded is the shipping lane between Ushant and Finisterre that there may be smudges of smoke as far as the eye can see. Away from this marine highway and inside the bay we are in a different world, back among sailing craft. Tunny boats from the Biscayan fishing ports of France sail serenely across the bluest of seas. These boats resemble winged insects, for from either side project long booms — gigantic fishing rods for the tunny lines.

So crowded is the shipping lane between Ushant and Finisterre that there may be smudges of smoke as far as the eye can see. Away from this marine highway and inside the bay we are in a different world, back among sailing craft. Tunny boats from the Biscayan fishing ports of France sail serenely across the bluest of seas. These boats resemble winged insects, for from either side project long booms — gigantic fishing rods for the tunny lines.

DEEPLY INDENTED BY THE BAY OF BISCAY, the Atlantic coast-

Coloured hulls and sails blend with blue sea and blue sky, making a gay picture. The spectacle is altogether different from the grey North Sea and the sober black and brown of the hulls and sails of the fishing craft which still use canvas.

When we get south of the usual beat of these tunny men we see on the horizon the peaks of the Cantabrian Mountains, with patches of snow on the higher summits. Here we find different craft. Long galleys with sixteen oars or more row out from the Spanish villages where the fishermen are too poor to afford motor boats. Steam vessels about fifty feet long go across the bay nearly to Ireland, bring their catches home and pack themselves behind the breakwaters of the harbours along the Cantabrian coast.

The shores of the bay are peopled by fishing folk whose individuality has survived invasion, wars, political changes, standardized clothes, the cinema and the radio. The most remarkable are the Basques, who live in the corner of the Bay of Biscay, on either side of the Pyrenees, which separate France from Spain.

There is no whaling in the bay now, but the Basques hunted the whale right up to the Arctic, and followed the cod to the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. Other nations copied and learnt from the Basques’ stout vessels, more seaworthy than their own.

The Bretons, splendid fishermen, live at the northern end of the Bay of Biscay, and the humble sardine is as important at this end of the Atlantic coast as at the southern tip of Spain. The sardine and the tunny are among the principal concerns of the fisherfolk, whether they are Bretons, Basques, Portuguese or Spanish. The tunny is sometimes over 10 feet long and weighs half a ton. The Spaniards trap tunny in enormously strong nets set offshore and buoyed, and small steamers have steamed into the nets and have had their propellers entangled in them. The canning of sardines and of tunny are important industries all along the coast.

Off the French coast of the Bay of Biscay are seen, in addition to fishing vessels, ocean ships bound to and from the ports. The greatest of these is Bordeaux, one of the chief ports of France. The coast from below the island of Ushant to the Gironde estuary, which leads to Bordeaux, trends generally to the south-

From the Gironde the low, sandy shore stretches south nearly to the River Bidassoa, the boundary between France and Spain. Then the coast turns west for several hundred miles to Cape Ortegal and afterwards south-

This part of the coast makes an extraordinary contrast with the coastlines on either side, as it has only one indentation, the Bassin d’Arcachon. The shore is a long waste of sand dunes with few landmarks. A few miles up the River Adour is the attractive town of Bayonne.

Biarritz, on the coast, has become one of the most famous seaside resorts in Europe, but has little to attract the lover of ships. The atmosphere of neighbouring Bayonne, or of St. Jean de Luz, is more congenial. St. Jean de Luz, although flourishing as a resort, is also a fishing port, and small craft find shelter behind its artificial breakwaters. The coast here trends to the southwest and the frontier is reached where the River Bidassoa separates Hendaye on the French side from Irun, which is in Spain.

A Forbidding Coast

East of this point the Pyrenees sweep across the neck of the Iberian Peninsula to the Mediterranean; westward the Cantabrian Mountains run for some 300 miles, along the north coast of Spain. So forbidding is this coast and so few are the safe harbours that the Spanish fishermen called it the Coast of Death. It is dangerous but beautiful, and the lack of safe harbours with ample water has been amended by building breakwaters and by constant dredging.

The ports, being off the ocean track, are unknown to Atlantic liner passengers; but a coastal service begins at San Sebastian and runs round the coast to the Mediterranean. San Sebastian rose to international fame as a seaside resort some years ago and rivalled Biarritz. With many other Spanish coast towns, it suffered during the Civil War of 1936. Bilbao is the port of shipment for iron ore mined in the mountains, and millions of tons have been shipped to Great Britain. The city, hemmed in by mountains, has drydocks and shipyards.

Santander, situated on the best natural harbour on this part of the coast, is a big port for shipping iron ore, and is also a noted seaside resort. Gijon, farther west, has a small artificial harbour for fishing vessels and a larger new harbour called Puerto Del Musel, which has been built to accommodate the larger vessels. These were attracted, until the outbreak of the Civil War, by the growth of the thriving city. There is no port of similar size between Gijon and Estaca Point, the northernmost cape of Spain. Some ten miles west of this cape is the better known Cape Ortegal.

A FISHING BOAT NEAR LA ROCHELLE. This Biscayan seaport lies in a bay protected by the islands of Re and Oleron, and has a fine harbour. A new harbour at La Pallice, three miles west, is one of the best on the west coast of France. Biscayan fishermen are engaged in the sardine and the tunny fisheries. Tunny fish are sometimes over 10 feet long and weigh half a ton. The canning of sardines and the canning of tunny are important industries along the coast.

In bad weather these ten miles are iong ones for small craft trying to beat round from the north coast to the tip of the Iberian Peninsula. Here, however, is a bight containing sheltered inlets, the best known of which are Ferrol and Corunna. Ferrol is a naval dockyard, and Corunna is the port of commercial and fishing vessels. Although Corunna dates back to the times of the Phoenicians, much of it is new and it is a clean, bright city built on a peninsula. On one side is a lovely bay with the bathing beach, and on the othei' is the harbour. The lighthouse, called the Tower of Hercules, is one of the most historic in the world, for it was founded by the Romans. Corunna is the northernmost of the series of ports along the west coast of the Iberian peninsula which figure so frequently in the story of British sea power, from the time of the Spanish Armada to the battle of Trafalgar and the Peninsular War.

From Corunna the coast continues south-

The port of Vigo is a calling place for liners on the South American run, and is a centre for the fishing industry. The city itself is a little disappointing after the white magnificence of Corunna, but the shores of the bay are entrancing. It is as well to make the most of it as this is the last good natural harbour north of Lisbon.

Having sailed from Vigo we pass the frontier and proceed south along the coast of Portugal to Oporto, the great port-

The road from the harbour of Leixoes to the city of Oporto passes along the north bank of the Douro and affords an enchanting view to anyone who delights in sailing vessels, for these are moored all along the bank. Among them are Newfoundland schooners which bring bacallido (salted and dried cod) across the Atlantic, and a variety of small craft, some of which are of undeniable antiquity and doubtful seaworthiness. The river has cut a canyon through the rock and is spanned by two spectacular bridges.

Having left the Douro, we sail south along a low and sandy coast with hills forming a ridge inland. Presently the coast becomes more rugged and we see Cape Mondego, and then Cape Carvoeiro, off which lie the Burlengas Islands and the rocks of Los Farilhoes. This part of the coast is subject to fog, and the islands have been the scene of many wrecks. A few years ago a large liner ran on to the rocks outward-

THE ROCK-

The coast forms two curves which end at Cape Roca, once known as the Rock of Lisbon, which is the westernmost point of the continent of Europe. It is a noble and impressive cape, and beyond it we see the hills of Cintra and the low-

The situation of the capital of Portugal is attractive. Between Lisbon and the sea the Tagus resembles a strait, about eight miles long and a mile wide, connecting a lake with the ocean. Above the city the Tagus widens into an expanse of water, from two to seven miles wide and some twelve miles long. This lake is called the Mar da Palho. The water-

The tide is swift, and is a bad master but a good servant. River craft of Oriental appearance, fishing vessels and liners, vessels of the Portuguese Navy (some of which were built in Great Britain), ferry steamers and seaplanes lie along this historic water-

The tide carries us swiftly to the mouth of the Tagus and shoots us between the sandbanks and into the Atlantic. We steer south and cut across bight between the mouth of the river and Cape Espichel. Here the coast turns sharply east for fourteen miles, to the entrance to the lagoon, at the head of which is Setubal. This port is famous for the quality of its grapes, and exports fruit, wines, cork, tinned sardines and salt obtained from salt pans on the lagoon. The coast turns south in two bights, the first of which ends at Cape Sines and the second at Cape St.Vincent.

Cape St. Vincent is one of the great capes of the world. The ancients called this south-

Shoal-

Off Cape St. Vincent were fought many sea battles, the most famous of which was that of 1797 when Nelson, under Jervis, disobeyed his superior’s orders and secured the defeat of the Spanish fleet. The headland is now the turning point for the ships of all nations. The cape is often obscured by fog, but the sea rolls into the caves in the base of the steep cliff and breaks with a warning roar that is heard for a considerable distance.

The south coast of Portugal is fringed with shoals, and there are no harbours suitable for large vessels, although there are some fishing ports used by coasters. Cape Santa Maria is the southern point of some sandy islands. Here the land trends north-

Cape Trafalgar, the northern side of the entrance of the Strait of Gibraltar, is twenty-

Before us is one of the sights of the world, the Rock of Gibraltar, with Europa Point at its seaward tip. Behind the two long moles are the masts and funnels of British warships berthed in the harbour. Anchored outside the north mole are liners which have called for mails. The superb Rock is the culminating spectacle of the wonderful coast.

THE FLEET IN HARBOUR AT GIBRALTAR. The fortress of Gibraltar, which is a British Crown Colony, occupies a rocky promontory near the southern extremity of Spain. The promontory is 2¾ miles long and about three-

You can read more on “The Discovery of America”, “First Voyage Round the World” and

“The Restless North Sea” on this website.