© Shipping Wonders of the World 2024 | Contents | Site Map | Contact Us | Cookie Policy

San Francisco

The Golden Gate, which is the entrance to the wonderful landlocked San Francisco Bay, is one of the most romantic and historic waterways of the North American continent. Famous in the days of sail, San Francisco is now a magnificent harbour for merchant and naval vessels

THE WATERFRONT OF SAN FRANCISCO is owned and has been developed by the State of California. Ferries ply between the city and the towns on the other shores of San Francisco Bay and about 45,000,000 passengers were carried annually until the opening of the first of two great bridges in 1936. These masterpieces of engineering will eventually connect the city with the neighbouring towns and pleasure resorts. At San Francisco there are forty-

ALTHOUGH most ports have a longer history than that of San Francisco, few have had a more eventful one. The city of 635,000 inhabitants lies just inside the Golden Gate, which is the entrance to the magnificent landlocked San Francisco Bay. Several times the city, which is less than a century old, has been devastated by fire, and on each occasion it has emerged greater than ever.

The total value of the water-

The Golden Gate is a strait about a mile wide and five miles long. This leads to the bay, a landlocked harbour forty-

There are, however, three floating dry docks and two graving docks, all owned by the Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation. The largest dry dock is 1,020 feet long, and 153 feet wide at the entrance, and has 40 feet of water on the sill at high water ordinary spring tides.

Although San Francisco is not on an island, the peninsula is so long that only one of the transcontinental railways made the detour necessary to reach it by rail, the others having their terminals at Oakland. Goods and passengers are ferried across from Oakland and from other cities on the bay. During the year about 45,000,000 passengers pass through the Ferry Building, as the terminus almost in the middle of San Francisco’s waterfront is called.

An unusual fact is that the waterfront is owned and has been developed by the State of California, which also owns and operates a belt railway. The belt railway has a track mileage of more than fifty miles. It links the three transcontinental railways with the piers and with more than a hundred industrial plants. This belt railway runs along the Embarcadero, the wide marginal way running along the waterfront. The limits of the waterfront are North Beach and, in the south, Hunters Point, and between them are the piers and wharves.

Facilities include forty-

San Francisco is not a one-

Chief items of export are petroleum and petroleum products, barley, canned goods, dried and fresh fruits, lumber, flour, rice, and canned and cured fish. About one-

Within the period from 1920 to 1930 general cargo movement was nearly doubled. Then came the depression which affected all American ports from midsummer 1930 to midsummer 1933, when trade began to revive. Then tonnage levels showed definite gains. Cargo handled over the piers reached the 10,000,000-

Facilities at the port include a shipside refrigeration terminal, a grain terminal, a banana terminal, pipe lines, tanks for handling vegetable oils and molasses, a fumigation plant and two shipside terminals for the concentration of general cargo. At Fisherman’s Lagoon more than 300 fishing boats can be accommodated. In the sardine fishing fleet there are more than 150 boats. Their home port is San Pedro, California, but they spend seven months of the year in San Francisco Harbour and fish off the Golden Gate.

Effects of the Gold Rush

San Francisco is the home port of twenty large American steamship lines. More than forty foreign lines maintain offices and agencies in the city. Altogether, 146 steamship lines operate regularly at the port, and more than 500 ships call every month.

In many ways the story of the rise of this great port is abnormal. Francis Drake and other seafaring adventurers who sailed up or down the long coast of Western America in quest of an anchorage missed the Golden Gate and the wonderful harbour — just the place they wanted to find — inside it. The first visitors were the Spaniards, Portola and de Ayala, as late as 1775. Spanish soldiers and missionaries were the first settlers on the peninsula between the bay and the Pacific. When the Mexicans rebelled against Spain, California became Mexican, but later became one of the United States.

In 1848, when gold was discovered in California, there were fewer than 1,000 people in San Francisco, but in one year the population rose to 20,000. The gold rush of 1849 was one of the most remarkable in the grim story of man’s craving for the yellow metal, and had a marked effect on the shipping of the period. No one in these days would think of going round Cape Horn to travel from New York to San Francisco, but that was the way many of the old-

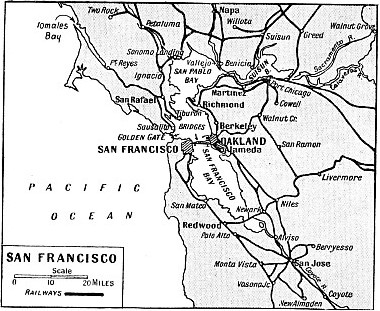

SAN FRANCISCO BAY, about 48 miles long and 13 miles wide, is entered through the famous Golden Gate, which is 5 miles long and about a mile wide. Since 1936 San Francisco Bay has been spanned by a colossal bridge, and a magnificent bridge across the Golden Gate was due for completion in the following year. Thus it is no longer necessary to make a detour round the Bay.

There was no transcontinental railway; the mighty range of the Sierra Nevada was one great obstacle, and another was the Red Indian. By a coincidence the steamship California, which had left the Atlantic side to go round the Horn to open the mail service between New York and California via the Isthmus of Panama, was on her way when news of the gold swept across America. Men travelled in steamships to the Atlantic side of the isthmus, crossed to Panama and waited for the California. She arrived crammed with gold-

The steamships on the run between Panama and San Francisco had one great advantage over the sailing ships: their skippers did manage to get the ships out of the Golden Gate. Many a sailing ship that sailed in never sailed out. Crews deserted to a man, and some ships lay so long in harbour that they rotted. The price of labour was so high that it was not worth while to repair the vessels. Some of the ships arrived in a sorry state, as the rush to get to California was so great that any vessel whose pumps outpaced her leaks was good enough for the impatient gold-

San Francisco was the craziest port in those days and surprised even New Yorkers. The rent of a palace was demanded for mean shacks, and every form of labour was at a premium. Every passenger landing at the port was sure he was at last on the road to riches, and the people on shore took their toll. All this prosperity was imaginary, and the bubble burst.

Even before the eventful 1849 had elapsed the canvas city had its first fire. In May 1851 there was a second blaze, and next month a third, so the use of tents was forbidden. Trees were felled and sawn into thin boards which were rapidly nailed together to form homes and warehouses. By then, too. the value of the site as a port was beginning to be appreciated, and the shipbuilders of the eastern States began to build swift clippers to send to the growing city. Fast as these ships were they could not compete with the Panama steamers as mail carriers. Steamer Day, the day before the departure of the steamer for Panama, became an institution. Every merchant in the port wrote his mail on this day.

Attracting, as California did, men from all corners of the earth, it is not surprising that San Francisco soon became notorious as the toughest of ports. To the world at large it was ’Frisco. In recent years great improvements have been made and the citizens do not like to have the name of the port abbreviated. So long as memories of sail remain, however, stories of the crimps of ’Frisco will be told, for these scamps flourished over a long period.

San Francisco was one of the last ports of the sailing ship. The long voyage round the Horn and the vast distances across the Pacific gave the sailing vessel a fighting chance. As sailors became scarce the power of the crimps of the port grew. At one time the San Francisco crimps demanded 70 dollars (£14) per seaman delivered on board as against the New York price of 23 dollars (£4 12s.).

Kidnapped and Drugged

The boarding-

The vigour of the inhabitants, however, the wonderful resources of the country that were rapidly developed, and the natural advantages of the bay made San Francisco the key port of the western seaboard of America. The opening of the Panama Canal shortened the sea route between New York and San Francisco by 7,873 nautical miles, and added still further to the trade of the port. The transcontinental railways and air lines which terminate at the port have put San Francisco on the quickest route from Europe to the Far East and Australasia.

Because of the width of the bay between San Francisco and Oakland, the city and port opposite, an enormous ferry traffic developed. A bridge to end the isolation of San Francisco was proposed as far back as 1867, but engineering had not advanced sufficiently to conquer the difficulties. The traffic grew to such proportions that in 1929 both cities provided funds for a survey and a route was selected.

The San Francisco-

A further feat of engineering is involved in the Golden Gate Bridge, the link between San Francisco and the northern woods and valleys. The length of the main span of this outstanding suspension bridge is 4,100 feet.

These two engineering masterpieces enhance the position which San Francisco holds as the focal point of the Pacific Coast of North America.

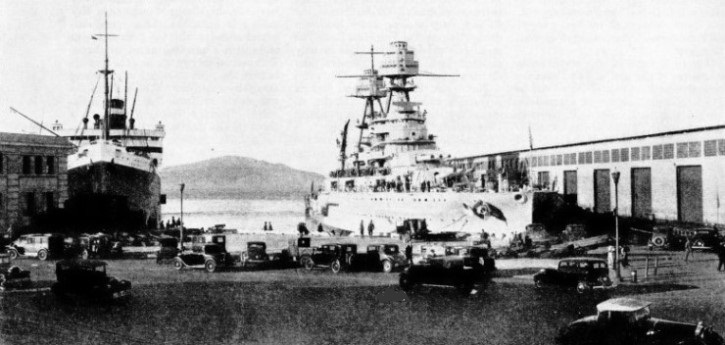

BERTHED SIDE BY SIDE at Piers 37 and 39 of San Francisco Harbour are the battleship Pennsylvania, 33,100 tons displacement, and the American Line’s twin-

You can read more on “American Shipping”, “New York” and “Seattle, Washington” on this website.