© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Seamanship Today

A sudden emergency is often the supreme test of the quality of seamanship, although the ordinary routine work in the handling of a modern vessel demands a high standard of efficiency and reliability

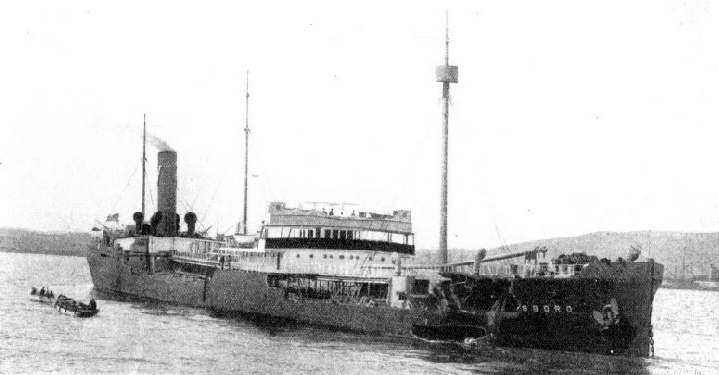

AFTER A COLLISION AT SEA a ship may be saved by seamanship in spite of severe damage. The Paulsboro (above), after a collision with the Memnon in May 1919, was safely brought to port although she was down by the head and difficult to steer. A vessel of 6,699 tons gross, the Paulsboro has a length of 435 feet, a beam of 56 feet and a depth of 33 ft. 5 in.

THE craft of the sailor may be divided into two broad sections, navigation and seamanship. Navigation is relatively simple, but seamanship is complex and covers many different subjects. There are many elementary sections of seamanship, sections which every sailor is expected to master whether he is in the forecastle or in the afterguard, but above all, the prime test of seamanship is the ability to rise to an emergency in the sailor’s eternal battle with the elements.

It is not stretching the term too far to say that the first element of seamanship is the ability to fit in with the ship’s officers and men, and the ability to be a good messmate and to help in the smooth running of the community. Among the greatest points are, perhaps, cleanliness and tidiness, which are the only possible means of making restricted quarters tolerable. The acquisition of these two qualities is one of the greatest justifications of the training ships and establishments round the coast, for ship routine becomes second nature to the boy when he is still at the most impressionable age and is sometimes difficult to acquire when he is older. Such factors are generally neglected when seamanship is considered as such, although they are important and form an integral part of the sailor’s training.

Perhaps the first and most elementary point of seamanship is knotting and splicing. In ordinary circumstances knotting and splicing is not what it was in the old days of sail, but there is always the possibility of an emergency which demands skill, quickness and care. The art was formerly regarded as the prime test of seamanship, not so much by the way the knot was made as by the way the rope was handled. The real sailor would treat it almost as if it were of silk.

Knotting, using the phrase in its narrowest sense, and excluding bends and hitches, is virtually confined in a modern steamer to fancy work. Turks’ Heads, Matthew Walkers, stopper knots and the like, may appear out of place in a workaday tramp, but they are, after all, an indication of the pride of seamanship which makes the sailor, and in an emergency always proves the best man. This pride was formerly shown in making ornamental rope handles and other fittings to the men’s

sea chests. In a passenger liner, especially one engaged in cruising, neat and expert knotting work is always appreciated.

Bends and hitches are always liable to be demanded, especially in cargo ships, popularly believed to carry only “sea labourers”, where it is often an awkward job to make fast the cargo gear to a difficult hoist. In all such operations due allowance has to be made, for an extra strain not previously reckoned with which will cause a break and disaster. Such work does not demand nearly as much knowledge as the complicated rig of an old sailing ship and comparatively few bends and hitches have to be known nowadays.

There is the bowline, often called the king of knots, which cannot jam and if properly made will never slip. There are the half hitch, clove hitch, rolling hitch, timber hitch and fisherman’s bend, which are in frequent use, and less frequently the figure-

The true sailor always takes particular care of his ship’s ropes, no matter what their purpose, when they are not in use. When they are stored the great enemy is dry rot and in this the careful sailor is against the neglect of many modern shipbuilders to provide proper stowage. It is remarkable how quickly rope is spoiled by grit working into its strands. When alongside a quay there is always the possibility of sand, and at sea the cinders from the funnel can do an immense amount of harm unless the rope on deck is properly protected and carefully examined.

Splicing, or repairing a broken rope by intertwining its strands, is another job of seamanship and is much more difficult with the modern wire in use to-

With canvas work, too, the change from sail to power has made an immense difference. In the old days most of the ships carried sailmakers whose particular job was to keep the canvas in good repair, and in many ships to make all the sails that were needed without troubling the lofts ashore. These sailmakers had their privileged position in the ship, but every man on board who made any claim to being a sailor, from the apprentice upwards, took a pride in the way he could handle the needle and palm and could do a sailmaker’s job in an emergency. To the apprentice there was no more pleasant work allocated than that of helping the sailmaker, even if it was little more than passing the heavy canvas to him.

The steamer and motorship have far less canvas on board than the old sailing ship, and more is done in the factories ashore and delivered on board complete. But there is plenty to do even to-

In almost every ship there is canvas work to be done on the bridge dodgers and screens, similar fittings for the crow’s nest, the covers for the boats and their sails. Fire and wash-

Importance of Boat Work

Above all there are the tarpaulins to go over the hatch-

These tarpaulins are secured with battens and wedges, but there may still be need for further protection, and it is a seaman’s job to provide it. The biggest ropes in the ship, used for mooring and towing, can be coiled down on the fore-

When bad weather is expected everything on deck has to be carefully secured and lashed down, especially forward, and it really needs seamanship to direct the operation and to carry it out. The entrance pipes into the chain lockers may admit much water if the fore decks are awash, and the ventilators also want attention. The boats, which are swung inboard as far as possible, have to be properly made fast. In a ship which carries her emergency boats swung out at all times, ready to be lowered without a moment’s delay if a man is overboard, they must be “griped to”, for if there is any opportunity given they will soon smash themselves against the rails and davits in bad weather.

Boat work is one of the most important tests of seamanship. When scores of British sailing ships used out-

Many officers are still keen on boat work, and they take crews out in their spare time whenever opportunity offers. The modern merchant ship, however, cuts down her idle time as much as possible, as being sheer loss to the owners, and these opportunities do not always present themselves.

Recently there has been a certain revival because of the growth of pleasure cruising by passenger liners, for it is seldom that a cruise does not include at least a few ports at which the passengers have to be landed and re-

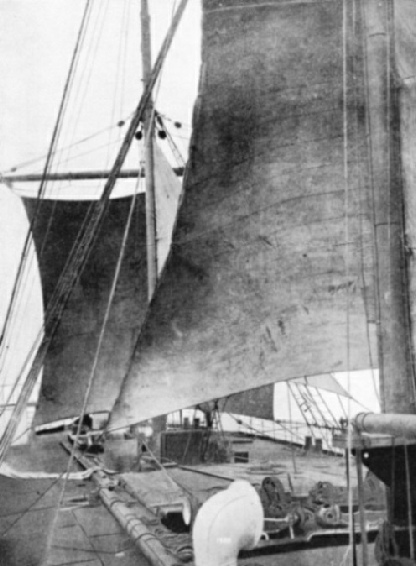

A STEAMSHIP UNDER SAIL. The Federal liner Norfolk was a four-

For the proper use of the ship’s boats, as lifeboats in the event of emergency, the Board of Trade and similar bodies in most other countries now take special care of the standard of seamanship, and insist on everybody who helps to man the boats having one of their lifeboat certificates, which are not granted without a thorough examination. If a ship does come to grief, her lifeboats will normally make for the nearest land, and the chances are that they will have to be beached through a surf, one of the most difficult things in boat work.

Of more routine nature, occurring every day in every ship, is helmsmanship, the steering of a vessel, which is generally entrusted to special quartermasters. Steering a steamer or motorship is a much more simple job than steering one of the old sailing ships, when a careful eye had to be kept on the wind as well as on the compass course. Helmsmanship, however, is still a matter which demands skill and constant attention, for poor steering is not only liable to cause damage through the ship taking heavy seas in the wrong way, but also demands more power to overcome the constant resistance of the rudder.

The helmsman always has to know his ship, for no two vessels, even sister ships built on adjacent slips in the same yard, behave in exactly the same way. In a single-

The helmsman has to think in cooperation with his officer, especially when he is conning the ship on to a new course, otherwise there will be a big wobble which may be dangerous, and the great thing is to get his mind ahead of what the ship is going to do next. For instance, he must steady his helm before the ship’s head gets as far as it is wanted, otherwise it will be much too far before he knows where he is, and a lot more helm will be necessary to get it back again.

Anchor work to-

Skill in Emergency

Even the job of anchoring demands seamanship, for with a big ship too great or sudden a strain will mean a broken cable and a lost anchor, and in a strong tideway, especially where the channel is narrow’, the anchors have to be placed to a nicety to let the ship swing with the tide in safety and without inconveniencing other ships in the neighbourhood.

When two anchors are down, as is often necessary in a strong current, there is always the possibility of their crossing or getting a turn in the cables as the ship is influenced by wind and tide. A foul cable wants a lot of clearing, and the handling of the heavy weights involved demands seamanship, as does also getting an anchor foul on the bottom or having the cable round its flukes. A modern ship’s anchor is a heavy thing to handle, and one of the essentials of seamanship is the ability to handle weights with the greatest ease and safety.

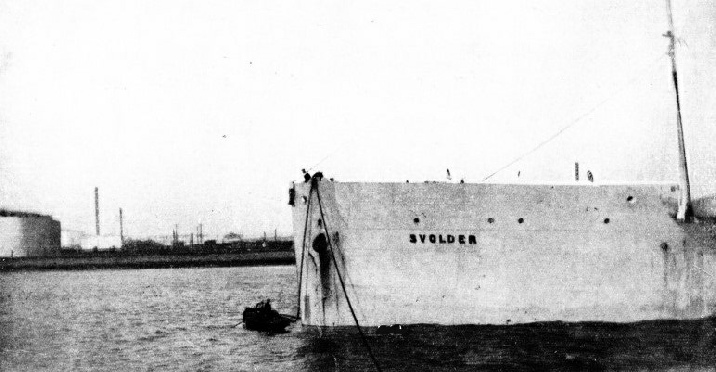

Somewhat akin to anchoring is mooring a ship to a buoy, which can be a fine test of seamanship. A buoy is generally in a tideway, and it is necessary to bring the ship up to it and hold her there during the operation, in spite of the influences of wind and tide. Usually watermen who are accustomed to the port and its conditions are employed to help in this work, but they are not always available, and in any circumstances a good deal of seamanship is demanded of the crew.

To begin with it is generally necessary to clear a hawse-

All these things call for seamanship, to a greater or lesser degree, in the ordinary working of the ship upon her lawful occasions, but even with the biggest and best managed vessels, running to railway schedule between two ports, there is always the chance of an emergency arising in which only seamanship can avoid disaster.

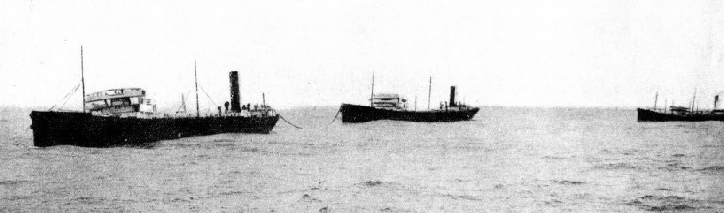

TOWING A DISABLED SHIP is an operation often demanding fine seamanship. In March 1916 the oil tanker San Onofre, 9,717 tons gross, broke down south of Cape Race, Newfoundland. The tanker Ashtabula, 7,025 tons gross, was the first to reach her, but additional help was necessary as the San Onofre’s steering was out of action. The San Gregorio, 9,594 tons gross, took her in tow, with the Ashtabula made fast for steering purposes.

One of the old jobs of seamanship which, in the opinion of many authorities, might have averted a number of recent disasters, was the rigging of an efficient sea anchor which would permit a ship to ride out the worst of weather head to sea. This was often done in sail, a big iron ring and a canvas cone being carried, but it is doubtful whether many modern steamers carry such a device. A substitute, however, can be easily made with a cargo boom, a sail or a tarpaulin, and a certain amount of chain and a spare anchor to keep the contrivance the right way up and doing its work. If a sea anchor is made it is generally used in conjunction with a certain amount of oil discharged into the water to check the breaking of the seas. In default of even an improvised sea anchor a good deal can be done by paying out chain cable from the hawsepipe forward.

If the ship is in shallow water where a nasty sea can be raised the chain will rest on the bottom and prove exceedingly efficient. When a modern ship leaks badly at sea there is not much to be done except to pump, and that is the engineer’s job with the big power pumps which are provided to-

If, on the other hand, a ship is damaged by collision, seamanship may well save her in spite of the appalling damage done by the impact of two big ships. In the Navy they have special collision mats, which are lowered over the side in such a way that they cover the hole made by the collision and are forced into it by the pressure of water. Some few well-

After a collision, when a compartment is flooded, it may also be necessary to shore up a bulkhead to help it resist the pressure of water on the other side, and it wants a seaman to get just the right timbers to stand the strain and to place them in exactly the right positions.

As a general rule, to patch up a steamer after an accident is a job of fine engineering rather than of seamanship, and some magnificent feats have been performed by the engine-

Occasionally, with a fractured tail shaft, for instance, tipping the ship in such a way that her bow is put down and her stern is brought out of the water demands a good deal of sailor-

One of the best remembered of these feats of seamanship is the story of the Federal liner Norfolk under Captain Corner in 1906. She was crossing the Indian Ocean from Durban to Albany (Western Australia) in ballast when the propeller shaft fractured and the engine began to race madly as the screw dropped off. Nothing could be done to put the damage right, but Captain Corner was an old sailing ship man who had, moreover, devoted many years of his life to the training of cadets. He determined to sail the ship to port. It would have been impossible to have found a ship less promising for this feat, for she was a modern type of four-

A COLLISION AVERTED by the skilful handling of ships and tugs in the River Avon, This remarkable photograph was taken from the Clifton Suspension Bridge. The strength of tides and currents, particularly in tidal rivers, greatly complicates the work of tugs handling large ships.

As with most modern cargo ships, she was well supplied with derricks. The first job was to unship these and use such as were suitable for conversion into jury yards. Every man in the crew who could handle a needle and palm in the old way was employed sewing tarpaulins together to make some sort of square rig, sufficient to keep her under command and let her blow towards Australia. One derrick was rigged over the bow to make a bowsprit and one was crossed on each of her four masts as a yard. The best that could be hoped for was that she would blow along on a reasonably straight course, and for this purpose she was rigged with the four squaresails, two headsails and several trysails, all made out of tarpaulins normally used for covering her hatches.

It would have been a fine feat of seamanship to have got the vessel into port had the weather remained fine and everything been in her favour. A gale, however, sprang up two days after the accident, and she had to take in a good deal of her improvised canvas, much of the remainder being split and rendered useless. For four days she drifted, generally broadside on to the sea, but finally she was taken into a safe position between Rottnest Island and the mainland of Western Australia, where tugs met her and took charge. While she was under this extraordinary jury rig, her best day’s run was 132 miles. Had it not been for the magnificent seamanship of Captain Corner and his crew it is difficult to say what would have happened, for the accident occurred in waters where she might have drifted for weeks without meeting another ship. It is possible that her crew would finally have had to abandon her.

Towing a disabled ship at sea, the dream of every sailor because of the salvage to be earned, is another operation demanding fine seamanship. If the disabled ship is derelict, which means bigger salvage still, boarding her by boat is often a difficult operation, for there is nobody on board to help and the ship may be rolling heavily. If she has been abandoned, however, it is more than probable that her boat falls will be hanging down from the davit heads, and the salvage party has to make the most of these to scramble on board. Once one or two have gained her deck they can help the others, but their task is not likely to be an easy one.

Even when the ship to be helped has a full crew ready to render every assistance, ocean salvage is always a job calling for the highest skill and the steadiest nerve. The first thing to be done is to establish communication, and in this there is a big risk of collision. More than one instance has occurred of a ship sinking the vessel that she is trying to help, or even of being sunk herself.

Jury Rudders for Emergencies

Nowadays most well-

The steamship sailor has comparatively little opportunity of rigging a jury, which was a frequent experience of the old sailing-

One aspect of seamanship which must not be forgotten is meteorology. This is still of great importance in spite of all the wireless warnings and messages which are sent out. Even the biggest and best-

MOORING TO A BUOY IN MIDSTREAM is a fine test of seamanship. A large ship must be held against the influence of the tide while the operations are carried out, sometimes with the help of watermen, and the ship must be so placed as not to interfere with other shipping. The Svolder, a Norwegian tanker of 6,362 tons gross, has a length of 403 ft. 4 in., a beam of 55 ft. 4 in. and a depth of 32 feet.

You can read more on “Handling the Sailing Ship”, “Instruments of Navigation” and

“Safety at Sea” on this website.