© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Safety at Sea

The risk of serious danger from accidents at sea has been considerably reduced by the introduction of strict regulation governing the loading of ships and by the perfection of such equipment as lifeboats, wireless and the like in every type of merchant vessel

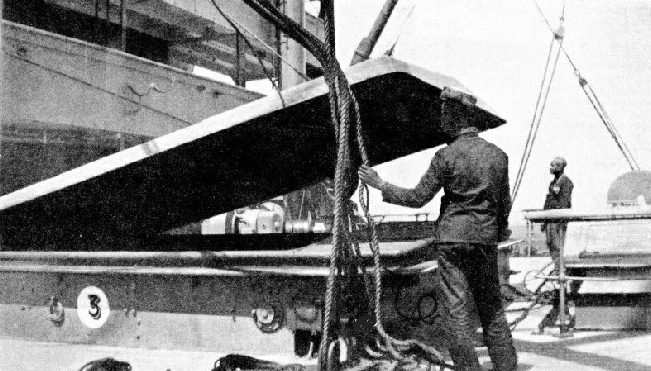

BOAT DRILL IN A CARGO LINER. The davits in the Craftsman were of the “goose-

EVERY possible precaution is now taken to secure the safety of the ship, her cargo and people, but in the old days it seems to have been regarded as a sort of sacrilege to interfere with Providence in that matter. There were various rules for the measurement of ships, and occasionally for their construction for special purposes, but few of these rules included much consideration for the ship’s safety.

Of the conspicuous exceptions one was the shipping law passed in about 1288 by the Swedish town of Visby, which then had a strong influence over the affairs of the Hanseatic League. This law provided for a load line and a heavy fine for any owner who loaded his ship beyond it. The other notable exception was in the fifteenth century, when the Council of the Doge of Venice published a code of regulations for the safe stowage of cargo, especially deck or inflammable cargo, and the proper ballasting of ships. To secure its enforcement they appointed a committee which consisted of owners, merchants and seamen. With these exceptions the matter of safety at sea was left to private interests. These interests were liable to clash. The less reputable owner wanted to load as much as he possibly could without any consideration of safety, but the better type of owner and the underwriter pulled in the opposite direction. As the general design of ships improved to enable them to cover the new shipping routes, naval architecture as a whole improved and stability was studied, but there were no laws for the assurance of safe loading.

In the middle of the eighteenth century the East Indiaman Duke of Grafton was so badly overloaded by the company’s agents in the East that she nearly foundered. The water for her big complement had to be stowed on deck and finally the masts had to be cut away and a large part of the cargo thrown overboard to save her from foundering. This incident impressed the members of the Court of the East India Company, who some time afterwards issued orders against overloading and regulated the ships’ draught on their size. The underwriters objected to overloading and Lloyd’s List of Ships for 1774 gave particulars of draught amidships. The only form of regulation, however, was the amount of the insurance premium, although in 1834 a Committee appointed by Lloyd’s proposed to secure safety by a rough and ready method of calculating the freeboard necessary. This scheme was improved upon by the Liverpool underwriters, but it was purely voluntary and many owners ignored it. They paid higher premiums as the price of higher profits. Unfortunately Government contracts that were cut to the bone were the cause of many owners ignoring safety.

It was the famous agitation generally associated with the name of Samuel Plimsoll that was the real turning point, although there were other men who deserve their share of the credit. Plimsoll was a doughty fighter, and although his actions were not always judicious, and he often lost a point through his impetuosity, he worked wholeheartedly for the safety of the British seaman, and for the abolition of what he so graphically described as “coffin ships”. To him must always go the great credit for the success of the campaign, but the agitation was started in 1866 by James Hall, a North Country shipowner who saw the appalling losses in the coastal trade. Many others were similarly concerned.

Samuel Plimsoll, a man who had known poverty and hardship, but who was then Member of Parliament for Derby, started his agitation for load lines in 1870. Three years later the Merchant Shipping Code Bill demanded that the draught should be shown at bow and stern and duly recorded, and also that the officers of the Board of Trade should be authorized to prevent ships from going to sea if there was any reason to apprehend danger. The bill was thrown out, but Plimsoll stuck to his guns and a Royal Commission on Unseaworthy Ships was appointed.

A Merchant Shipping Act was accordingly passed in 1875. This provided that a load line should be carried by all British ships carrying cargo. The weak point in the Act was that the owners were allowed to place the mark wherever they wished, and some of them placed it far too high.

The administration of the Act was also difficult and finally the Board of Trade called a conference with the registration societies. Lloyd’s Register then issued properly calculated tables for the position of the load lines of various types in 1882, but it was still entirely a matter for the shipowner whether he used them or not. Later the Board of Trade made its own regulations and a Load Line Committee considered the matter for a long time, eventually framing rules closely based on those of Lloyd’s Register.

Classification Societies

In 1890 load lines became compulsory. Their position was fixed by Lloyd’s Register rules of 1885, although the other classification societies had an equal right to mark freeboards. That right exists to-

The load line is a precaution against one danger only — that of the ship foundering because she is overloaded and too deep in the water. Whereas the problem of overloading excited so little interest in the old days, in sharp contrast to its importance to-

Many of the merchant adventurers of Queen Elizabeth’s day, unhandy with the pen as they were, took the trouble to write treatises on the proper design of ships and the means by which their seaworthiness could be improved Similar works have been written at intervals ever since and. with ship building regarded as a secret craft for so many years, they are our main source of information concerning naval architecture over a long period.

Everything is changed nowadays and the lives of the sailor and passenger are guarded at every point. The various registration societies, which work primarily in the interest of the underwriters, are in the closest co-

STEEL HATCH COVERS have an advantage over wooden covers in that they make the hatch almost as strong as the deck itself. The hatches and tonnage openings are always regarded as a weak spot, as they are often pounded by heavy seas. Steel covers of the type illustrated are the invention of Captain Sweeny, Marine Superintendent of the Peninsular and Oriental Line.

These precautionary measures start as soon as a ship is projected. Design, materials and workmanship are carefully checked and no vessel which might prove unsafe is allowed to be built. The Board of Trade and the societies all have authority over this, and nearly every ship is built under the supervision of one or other of the societies. Their surveyors are always in and out of the yards, testing every piece of material to be sure that it is up to standard, and keeping careful observation on the workmanship.

The most conspicuous precautionary measure is the Plimsoll Mark. This is painted on the side of the ship after careful calculations. It is a serious offence to paint out the mark and repaint it higher up, although this is known to have been done on many occasions.

The difficulty is to get all nations to measure their ships by the same standards, for until new regulations were agreed upon in 1932 some countries had rather vague ideas. The new regulations were made as elastic as possible. If a ship is of a nature, or carries a cargo, which minimizes the danger of foundering she is allowed to put her load line higher up. Yachts, fishing vessels and certain purely harbour or coastal ships of under 80 tons are relieved of the necessity of having a load line at all.

As far as the regulations go, Plimsoll’s dream has now virtually attained perfection and every ship going to sea should have sufficient freeboard, that is, height of side above water, to prevent her being overwhelmed except in extremely unusual circumstances. Most British ships, and certain others also, have the less conspicuous deck marks painted on their sides amidships indicating the position of each deck above water. The scantlings of the ship, on which her strength depends (the word originally meant timber cut in pieces) may be defined as the dimensions of the structural parts. The present regulations for scantlings are based on searching experiments over long periods, backed by practical experience, and the strict rules laid down have to be obeyed in the construction of every ship built under survey. A large number of vessels, however, are built with their scantlings far in excess of these standards.

Bulkheads and Watertight Doors

Of only slightly less importance than the scantlings is the subdivision of the ship by bulkheads. This not only localizes the effect of any accident but also gives the hull greater strength. Bulkheads were known in China at an early date, but in the days of the old sailing ships they were practically unknown in the West — a so-

It is almost impossible to tit a really efficient bulkhead into a wooden vessel. When steamers came in, however, the number of bulkheads was increased, and when the majority of ships were built of iron or steel the matter was put under proper regulation after long discussion and investigation by various committees.

The number of bulkheads that must be laid down is based on careful calculation of the reasonable limitation of the effect of accident; but roughly it may be taken that six bulkheads, dividing the ship into seven watertight compartments, are considered necessary for an ordinary ship 400 feet long and that one more bulkhead must be placed for every additional 80 feet of the ship’s length. Special types of vessel may demand more bulkheads, but it is seldom that the authorities will permit fewer.

Wherever possible the bulkheads are made without any openings, but in the working of an ordinary merchant ship, especially one carrying passengers, this is an impossible ideal and watertight doors are fitted where necessary. The Board of Trade keeps the number of these doors as small as possible, and has them placed as high in the ship as circumstances permit, so that there is more time available for closing them in the event of an accident. These doors are accurately made, with a packing of rubber or similar material, and they are extraordinarily effective.

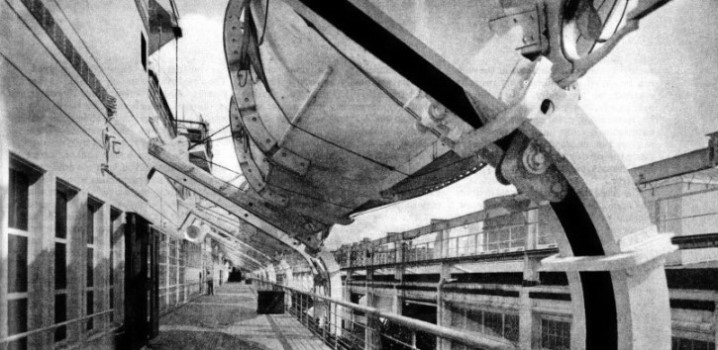

THE BOAT DECK OF A MODERN TRANSATLANTIC LINER. The Normandie is described in the chapter “The Triumph of the Normandie”. Her lifeboats are raised well above eye-

The majority are closed on the spot and held fast with big iron clips, but in the event of disaster to a big modern liner it is a big job to send members of the crew round to all the watertight doors, when every man may be needed to get out the lifeboats. So under various systems all the doors in the ship can be closed mechanically by pressing a button on the bridge. An indicator over this button shows clearly if a door has remained open for any reason. These automatic systems have saved many a ship, and in innumerable instances have made the sinking so slow that there has been ample time to get everybody away in safety.

The disadvantage of automatic doors was originally that passengers and crew, especially the stokehold crew, had a horror of being shut into a compartment without any chance of escape. People would often nullify all the precautions by placing some obstruction to prevent the doors from closing. This is unnecessary now, for all the systems have a method by which anybody shut in a compartment can let himself out without difficulty, the door closing again automatically as soon as he has passed through. It is doubtful whether any safety device has had greater care expended on it than the bulkhead and watertight door.

Allied to the bulkhead is the double bottom an inner skin built along the whole length of the bottom of many ships. This is a great safeguard in the event of stranding. The outer skin may be pierced or even torn right a way, but the inner skin will often keep the ship afloat. The double bottom is invariably divided into a number of tanks for various purposes, as for the storage of fresh and ballast water, and oil fuel. The inner skin, which forms the deck of the lower holds, is known as the tank top. Hence a ship is said to be “floating on her tank tops” when the bottom has been badly pierced. The weakest point of a ship, in her primary task of keeping out the water, is the deck, which must be pierced by various openings and hatches for the passage of cargo and people. These hatches are usually covered by a number of loose boards of heavy timber, fitting close together and in turn covered by a number of stout tarpaulins whose edges are carefully secured over the coamings. The greatest care has to be exercised in this, for heavy seas pounding on to the deck seem almost to have fingers which are skilful in tearing up some corner of the tarpaulins and weakening the whole defence.

The hatch covers, being so vulnerable, have to secure the approval of the authorities before they are fitted, and they should always be carefully inspected and surveyed. The routine is for the surveyor to examine them the moment the ship reaches her dock and before they are touched. With the old type of wooden cover the great danger was that, in taking them off and putting them on again, the corners were liable to be splintered away through hitting various objects. Some covers, therefore, have their edges strengthened by metal which cannot be splintered off.

As an additional precaution there are many types of steel hatch cover on the market, but as a rule the disadvantage is that the hatches occupy most of the deck and there is little space in which to stow the covers when the hatches are open. If it is possible to fit them, however, steel hatch covers in one piece have an advantage in that they make the hatch almost as strong as the deck round it.

The holds of a big cargo ship are gigantic caverns, and if they were not carefully designed they would be a source of great weakness. Formerly cross-

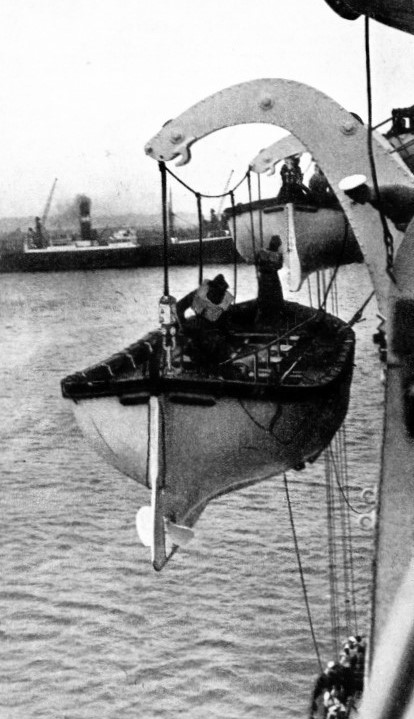

AN INGENIOUS TYPE OF LIFE-

So, as the great object of the naval designer is to give the necessary strength without undue expenditure of weight or money, great ingenuity has been shown in reducing the obstructions. The necessary strength has been obtained by various frames and girders which provide the strength without obstructing the hold, and the number of pillars has been cut down to four in most ships, one close to each corner of the hatch. In many ships the pillars have been eliminated altogether.

When the ship has been built, she is constantly being surveyed to be sure that she is kept in perfect condition. As far as the Board of Trade is concerned, passenger ships come under a different category from cargo ships, which are allowed to carry as many as twelve passengers but no more. When a ship is granted a passenger licence she is surveyed at least once a year under the Merchant Shipping Act, and a certificate is granted. She has to be put into dry dock, or on to a patent slip, so that such items as the hull, rudder and shafts may be inspected, but other items of her equipment are generally examined on board. The law does not insist on an annual inspection of cargo ships, but they are liable to be visited at any time, and it is rare for any deficiency to go undetected for long.

In addition to the Board of Trade inspections, the classification societies all have their own corps of surveyors who carry out periodical surveys of the various parts of the ship. Steamers classed with Lloyd’s Register, for instance, have their boilers surveyed annually by experienced officials.

These examinations get more and more strict and searching as the ship gets older. As far as possible the surveyors meet the convenience of the owners, and tie the ships up as little as possible by carrying out these surveys piecemeal as opportunity offers; but that does not mean that anything is neglected.

Risk of Boiler Explosions

A particular subject of survey is the propeller shaft, which is under constant supervision. It is a weak point, for if the machinery of a big ship is amidships there is a long length of steel shafting, subject to a tremendous strain, and liable to fail in spite of every care. It is not only that a dropped screw — the shaft generally parts at the extreme end — will render the ship helpless, but also, unless the power is cut off at once, the engines, suddenly released from the load of the screw in deep water, will race madly and the broken shaft may whip round and tear a huge hole in the plating of the ship. Many a fine vessel has been lost in this way.

The machinery of the ship, especially the boiler section, is subjected to the same careful supervision in building and throughout its life. In this the societies’ surveyors co-

Allied to the risk of explosion is the risk of fire. Many a fine ship has been lost at sea through fire, and many of these fires were really preventible. The Board of Trade and classification societies now pay as much attention to fire prevention as they do to seaworthiness.

A LINE-

The introduction of oil fuel brought a potential risk of fire in the engine-

The collision risk also is great and is duly recognized by the authorities. Every ship under way or anchored in the fairway at night must display the proper lights which will clearly indicate her character and actions to any other seafarer.

Certain signals are laid down for use in fog and a ship manoeuvring in a channel must signify her intentions to other ships by means of her steam whistle or siren. One blast means that the ship is steering a course to starboard, two blasts that she is steering to port, three blasts that her engines are going astern.

Four blasts make the local signal that is adopted in the London River and several other places and usually indicate that the ship, for the time being, is not under complete control, and that it is the business of other ships to keep clear. A big ship turning round in the Thames will use this signal, for in the tideway she is not easy to handle and may obstruct the river for some minutes.

During the latter part of the nineteenth century an international rule of the road was laid down, by which the chance of collisions at sea was minimized. Mr. Thomas Gray, a prominent Board of Trade official, invented a mnemonic rhyme which every sailor learnt by heart. One of the verses was:

“Meeting steamers do not dread

When you see three lights ahead.

Port your helm and show your red.

Perfect safety, go ahead”.

This and other rhymes served for years, but since the direct helm orders have been introduced the third line has to read:

“Starboard your rudder and show your red,”

which spoils the metre sadly.

The risk of stranding, although its effects are minimized by the double bottom, is avoided almost entirely by the equipment of the ship and the quality of her crew. Every country insists on efficient compasses, sounding gear and the like, being carried, but only a minimum number is specified. Gyro compasses, direction-

The authorities’ part is to insist on searching examinations before officers’ certificates are granted. Certain regulations are laid down for the. keeping of the lookout, and strong disciplinary measures are taken if a ship is wrecked by default.

After the means of preventing mishap, or limiting its effects, come the provisions for the safety of the personnel should disaster occur, and in this direction the authorities are no less active. The principal means are the lifeboats, and the State is concerned with their type, number and condition as well as with the ability of the crew to handle them in any circumstances.

It was the Titanic disaster of 1912 which focused public attention on the ship’s lifeboat and started the popular demand for “boats for all”. In Great Britain there had been regulations as to number and size ever since the famous Merchant Shipping Act of 1854, but it was seldom that sufficient boats were carried for every person. In the old ships carrying passengers under sail it is certain that the boats were invariably grossly inadequate for the passengers on board, and although it was not so bad in steam times, there were few, if any, passenger ships which had sufficient boats.

It is still an open question as to whether the policy of providing lifeboats for everyone is the right one, for although it gives an impression of safety, the top weight is so excessive that it helps the ship to take a heavy list as soon as an accident occurs. That will often prevent half the lifeboats from being used with any degree of safety.

It is still an open question as to whether the policy of providing lifeboats for everyone is the right one, for although it gives an impression of safety, the top weight is so excessive that it helps the ship to take a heavy list as soon as an accident occurs. That will often prevent half the lifeboats from being used with any degree of safety.

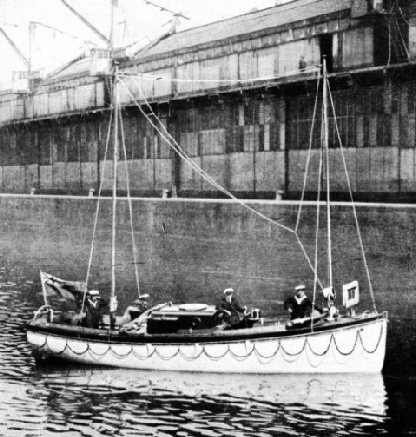

A WIRELESS EQUIPPED MOTOR LIFEBOAT from the Canadian Pacific liner Montclare, 16,314 tons gross. Lifeboats of this type are fitted with radio transmitters and receivers. The equipment relies on batteries which are kept charged by the ship’s dynamos ready for instant use. In addition to the wireless telegraph installation, which gives great range, wireless direction-

The present regulation for passenger ships, confirmed in the Safety Convention of 1929, is that sea-

The davits and other gear for lowering the boats are as important as the boats themselves, and the regulations are equally strict. The ordinary type of davit, which is still fitted in a large number of cargo ships and older passenger vessels, is the “goose-

When it is desired to use the boat one end is swung out first, as a rule the stern, which is taken as far aft as possible to give room for the forward end to be swung out past the davit in the same way. This type of davit can scarcely ever go wrong, but it takes several men to handle it and a good deal of time. Also it has the disadvantage that it cannot be made sufficiently large to take the boat well clear of the ship’s side, so that if she takes a list all the boats on one side are useless, or else they have to be lowered down her side at some risk.

Lifeboat Regulations

These disadvantages led to a number of improved davits being invented. The first radical improvement was in the 1850s, when the davit was lengthened and so shaped that the boat could always lie outside it, securely lashed in, although it was inside the rail of the ship.

This davit was hinged at the heel so that when wanted for use it was allowed to fall outwards and carried the boat well clear. In the famous Welin Quadrant davit the hinge at the heel was replaced by a quadrant of which the outer side was given teeth which engaged in a screw with a handle at the end. When the screw was turned the whole davit moved in or out, and the distance which the boats could be carried from the ship’s side depended on the height of the arms.

In the Welin-

are excessive weight and elaborate gear which can be choked and made useless by paint or dirt.

It is specially laid down in the regulations that davits and their gear must be strong enough to support the boats fully loaded and must be capable of handling them on the weather side of a ship, with a list of fifteen degrees. Considering the tremendous height of a modern liner’s side this means that the arms have to be extremely long to satisfy the regulations. The maximum weight of a loaded lifeboat is as much as 20 tons.

Each lifeboat has to be surveyed by the Board of Trade and certificated for the carriage of so many people according to its cubic capacity. Lifeboats are divided into five classes, and there is a strict code of regulations laid down as to their construction, strength, number of oars and similar items.

The ordinary familiar Board of Trade lifeboat, clinker-

To overcome the difficulty of rowing a boat which is crowded with people, various ingenious ideas have been tried. One is the Fleming lifeboat, which has a propeller, but instead of having an engine, the shaft which runs almost the whole length of the boat, is geared to a number of levers and is turned by their being moved backwards and forwards. Everybody in the boat can help to propel her without any skill. Such exercise may be welcome to passengers huddled together, half-

To overcome the difficulty of rowing a boat which is crowded with people, various ingenious ideas have been tried. One is the Fleming lifeboat, which has a propeller, but instead of having an engine, the shaft which runs almost the whole length of the boat, is geared to a number of levers and is turned by their being moved backwards and forwards. Everybody in the boat can help to propel her without any skill. Such exercise may be welcome to passengers huddled together, half-

LOWERING A FLEMING HAND-

Shortly before the war of 1914-

In addition to the boats the regulations insist that passenger ships shall carry buoyant apparatus. A popular form, seen in the excursion steamers round the coast, ferries and other small craft, is to have the seats built round airtight copper cases with lifelines looped round them. In the event of the ship going down these seats will float off and will support a large number of people clinging to the lines. They will not be comfortable in the water, but as it is reckoned that rescue parties will be quickly at hand they are efficient for their purpose.

In the big passenger ships this buoyant apparatus takes the form of rafts, again with lifelines looped round them, and in the event of any boats being stove-

Another point of equipment which was insisted upon by the Safety Convention of 1929 was that every ship must carry an efficient appliance for throwing a line. Sometimes this appliance is in the form of a rocket, sometimes it is a gun or pistol, and either method is capable of carrying a line a long distance. This would be useful principally if a ship were wrecked on shore, although it has often been used for other purposes.

As the wreck is almost invariably on a lee shore it is easy to understand that it is far better to throw the line from the ship to the shore, with the wind, than to rely on the shore rocket apparatus which has to carry against the gale. If a ship breaks down and has to be towed such apparatus is useful for carrying the heaving line, which will be attached to the towing hawser, without forcing the ships to approach one another so closely that there is danger of a collision.

Wireless Compulsory

Perhaps the greatest modern safeguard against absolute disaster at sea is in the vastly improved range of communication. In the old days the greatest dread was solitude. Anything might happen to a ship and nobody would be the wiser, or suspect anything until she became overdue. The appalling number of ships written off as missing was good evidence of that. Nowadays isolation is comparatively rare except among the smallest classes.

Before the invention of wireless a ship had only flares, blue lights or rockets to call help and at the best their range was limited. The supply also was often inadequate and a burning tar barrel as a substitute was apt to set fire to the ship. Rockets and the like still have to be carried, but the principal reliance is placed on wireless. Rarely does a ship send out an S.O.S. message without its being picked up by somebody and either answered or passed on to a ship in a better position to render aid.

All seagoing ships of over 1,600 tons have to carry wireless and must be able to send out an S.O.S. message and the position of the ship. Ingenious automatic receivers which do their work remarkably well are permitted in certain circumstances. The regulations insist that the wireless apparatus shall be of such a type, and so placed, that it shall be capable of use for as long as possible before the ship sinks.

It will be seen that the authorities, the owners and everybody connected with the sea have done all that they possibly could to reduce the risk which is inevitable when man and his works are pitted against Nature. In the end, how ever, it is the human element which counts for most, and the best means of obtaining safety at sea is to ship a well-

TAKING THE CREW OFF A STRANDED VESSEL. On September 17, 1918, the Baynyassa, a vessel of 4,937 tons gross, went ashore about 10 miles south of Agadir, on the west coast of Africa. A boat from H.M. rescue tug Crocodile is seen making for the Baynyassa, over which the seas are breaking dangerously. Alongside her, another ship, the Tupy, a Brazilian vessel of 2,822 tons gross, has also been stranded. The Baynyassa, built in 1915 as the Nyassa, was 400 feet long with a beam of 52 ft. 5 in. and a depth of 28 feet.

You can read more on “The Drama of Lifeboats”, “Marine Measurements” and

“Medals for Acts of Bravery” on this website.