© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

The Göta Canal System

The natural waterways of Sweden have been linked by the Trollhätte, Göta and Södertälje (Södertälje) Canals to form a route across the country from the port of Gothenburg, on the Kattegat, to Stockholm, the capital of Sweden. Of the total distance of 347 miles about one-

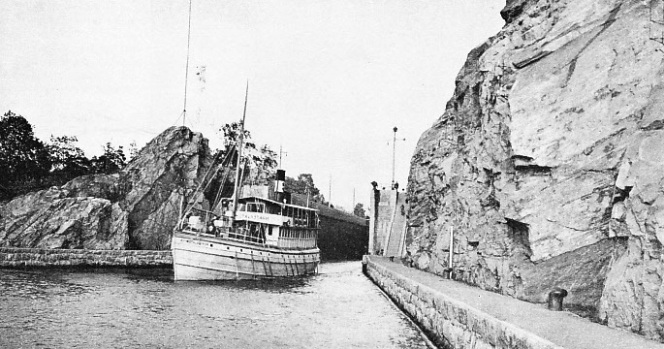

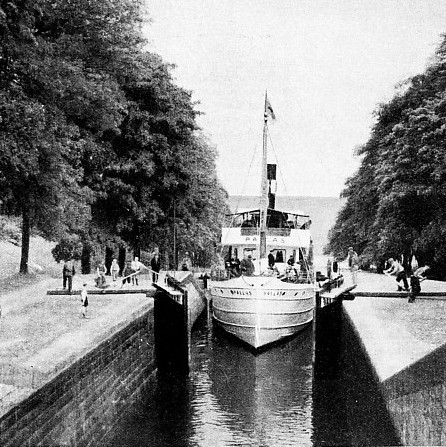

BLASTED FROM VIRGIN ROCK the locks at Trollhättan (“Witch’s Cap”) are unsurpassed on the system for grandeur. The locks were built to avoid the falls of the River Göta. Vessels up to 28S ft. 5 in. long and 41 feet in beam can use these locks. The Motalastrom, a vessel of 266 tons gross, belongs to the Göta Canal Company. She has a length of 96 ft. 6 in., a beam of 22 feet and a depth of 8 ft. 9 in.

AFTER more than a century of service, the Göta Canal route across Sweden remains one of the most interesting inland waterways in the world. It is a system of canals, rivers and lakes which links Sweden’s premier ocean port, Gothenburg, on the Kattegat, with the Baltic Sea and with Stockholm, the capital.

It is not a great highway for ocean shipping such as the Suez and Panama Canals, as the dimensions permit of small vessels only, but it performs an important function in the transport of the country. It is a clever piece of engineering and passes through beautiful scenery.

Scenically, there is nothing of that flatness and tameness usually associated with the word canal. In places the route is so narrow that vessels have little room between their sides and the banks, and during the journey they are raised by a series of locks to about 300 feet above sea-

About eight per cent of Sweden is covered by water, and lakes are more numerous than in most countries. Lake Vener (or Väner), 2,150 square miles, the largest lake in Europe outside Russia, and Lake Vetter (or Vätter), 730 square miles, the second largest lake in Sweden, are on the route of the system.

Thomas Telford, the Scottish road and canal engineer, planned the Göta Canal, which is linked with the development of the ocean steamship. At one time John Ericsson, then a boy of fourteen, was employed by his father, who worked on the building of the canal, to assist in surveying and making drawings. The quality of the boy’s work attracted the notice of Count von Platen, who was the maker of the canal.

Later the boy began a career as an inventor that affected world shipping and twice made the navies of the day obsolete. Ericsson invented a screw propeller, which altered all ships, including warships, and later built the ironclad Monitor, which defeated the Merrimac in the American Civil War and made the all-

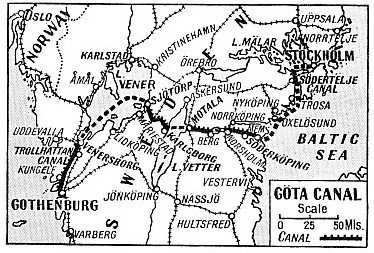

FROM STOCKHOLM TO GOTHENBURG vessels pass through the Södertelje Canal, which links Lake Mälar with the Baltic, the Göta Canal which runs from the Baltic to Lake Vetter and thence to Lake Vener, and the Trolhätte Canal and the River Göta, which join Lake Vener with Gothenburg. Steamers make this journey in fifty-

A study of the map of Sweden will show that the position of the two main lakes and smaller lakes suggests that they could be linked with canals and that the waterway could be extended to the coasts. This idea was considered centuries ago. Bishop Brask suggested a canal between Berg (on Lake Roxen) and Söderköping in a letter to the king in 1525. Work was begun, but the bishop had to flee the country. In the reign of Charles IX (1600-

Time and again the idea of a complete waterway came up and a little work was done, but the results were insignificant until the Trollhätte Canal was opened. This canal opened navigation between Lake Vener and the Kattegat by surmounting the obstacles which prevented the River Göta from being used. “Charles’s Ditch” avoided the first waterfalls in the river at Rånnum, but the Trollhätte Falls were for long insurmountable. The first attempt to circumvent the falls had ended in a considerable disaster.

After five years’ work, in 1755, the project was so near completion that rates for vessels using the canal had been drawn up, and the most difficult piece of construction, the dam at the Flottberg Falls, awaited only a few additions.

Sabotage by Peasants

One night, however, hundreds of planks were floated down. These piled up against the dam until the pressure caused it to give way in the morning when work-

Years passed before men had the heart to begin work again. This time, however, the effort was successful. The canal was opened in 1800. Part of it was blasted out of the rock. At various times the canal has been enlarged and in 1916 it was rebuilt.

The opening of the Trollhätte Canal was a spur to the project of continuing from Lake Vener to the Baltic Sea. The driving force behind the larger scheme was Count Baltzar Bogislaus von Platen, and he was ordered by the king to make investigations. He called Telford in and a survey was made. Later Telford was knighted by the King of Sweden for his work on the Göta Canal.

Count von Platen died before the canal was completed, but his determination carried it past difficulty after difficulty. The greatest trouble was money. Finally the canal cost more than ten times the original estimate, so that the complaints of those who had subscribed to it were understandable. So long did the work take that wages rose to three times the amount estimated when the canal had been begun.

A start was made at three different places simultaneously, and the route was divided into sections, each with a separate administration. The Göta Canal runs along the edge of the Fredsberg Bog to Lake Viken, 300 feet high, passing from light, watery, sandy soil to rock near the lake. Forsvik is the connecting point between Lakes Viken and Botten, and at Rödesund Lake Botten joins Lake Vetter.

Vessels cross Lake Vetter to Motala and then proceed to Lake Boren. The bottom of the canal in places has to be covered with clay to prevent the water from being lost in the loose soil After the crossing of Lake Boren to Borensberg the route traverses swampy and stony ground in turn, and then through stony and loose soil from Ruda to Ljung. Berg, between Ljung and Lake Roxen, has fifteen sluices in about 10,000 feet, and the ground is so porous that at one place the canal had to be dug deeper and wider, so that the bottom and sides could be filled with clay to retain the water.

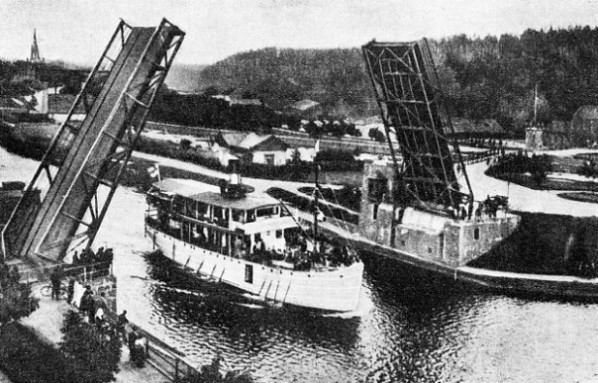

A LIFTING ROAD BRIDGE crosses the

Trollhätte Canal at Trollhättan. From Venersborg, the south of Lake Vener, the River Göta (Göta Alv) flows sdouth to Gotherbuurg. To make the river navigable, the Trollhätte Canal, which avoids the waterfalls at Trollhättan, was built in 1800.

The canal passes Norsholm, and then Jäverstad and Carlsborg between Lake Asplången and Söderköping, and reaches its terminus at Mem. This last section of the canal was difficult owing to swamps, as the banks kept slipping and the canal had to be shifted in one section of the work. Mem is 242 miles from Gothenburg and is situated on an arm of the Baltic Sea. Steamers proceed to Stockholm by way of the Södertelje Canal.

During the building, work was concentrated upon continuing the stretch opened up by the linking of Lake Vener with the sea, and work was pressed forward at Sjötorp, Forsvik and Motala. The entire canal was opened in 1832, but the final inspection was not made until the following year.

The passenger steamers on the canal route start from a landing stage at Riddarholmen (Knights’ Island) on the Lake Mälar side of the city of Stockholm. Stockholm is situated at the point where this important lake makes its way into the Baltic. The city is so intersected by waterways that it is called “the Venice of the North”. Part of the harbour works, which are among the most extensive in Sweden, are partly on the fresh-

Because of its site Stockholm thus commands two types of water transport, those for inland waterways and those for the sea. Although it is not such a large port as Gothenburg for trans-

“King's Hat” Island

A vessel bound across Sweden from Stockholm leaves the landing stage at Riddarholmen, turns her stern to the old route to the Baltic, and steams in the fresh water of the lake in a direction that is generally west. The steamer keeps to the south shore of the lake. The coast to port and the islands to starboard are dotted with villas and summer residences. Lake Mälar contains thousands of islands and islets, some of which have legends of the brave days of old. On the highest point of the island of Kungshatt (“King’s Hat”), which lies to starboard, is a hat on top of a pole to recall the story that King Erik Väderhatt escaped from his pursuers by riding his horse over the rocks into the water and swimming across to Södertörn.

The channel narrows for the beautiful sound of Bockholm (Buck Island) and then opens out and turns south into the Lina Sound and approaches Södertelje for the entrance of the canal. At one time Lake Mälar was connected with the Baltic, but the rising of the land blocked it for a few miles, and as far back as 1436 an unsuccessful effort was made to dig a canal.

The Södertelje Canal was built in 1819 and served for over a century until 1924, when it was widened and rebuilt. It is three miles long, 23 feet deep in the middle, and has a basic width of 78 ft. 9 in. The new sluice is a fine piece of modern engineering. It is 443 feet long, 65 ft. 7 in. wide at the gateway and 24 ft. 7 in. Deep.

One man operates everything from a control house at the southern lock gates. He opens and closes the 300-

Having emerged from the canal the vessel enters Hallsfjärden, as this arm of the Baltic is called. At first it is narrow, but it widens as the ship steams south and passes the long island of Mörkö. On a rock called Stenskär (Stone Skerry), near the end of the island, is the first of the-

Having emerged from the canal the vessel enters Hallsfjärden, as this arm of the Baltic is called. At first it is narrow, but it widens as the ship steams south and passes the long island of Mörkö. On a rock called Stenskär (Stone Skerry), near the end of the island, is the first of the-

the navigator can tell whether he is standing into danger or not, but the navigation is so intricate that considerable local knowledge is necessary.

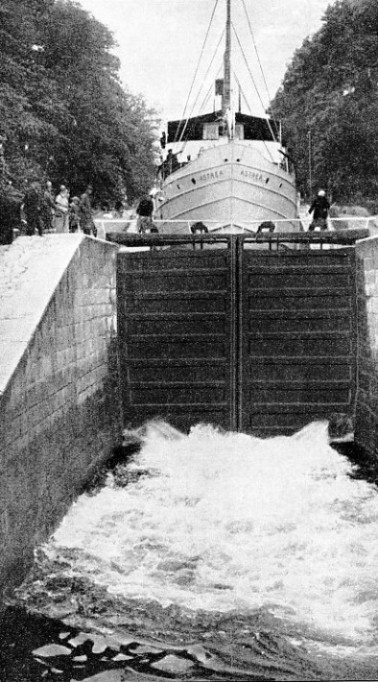

IN THE LOCKS AT BORENSHULT, vessels rise from the level of Lake Boren. Five locks at Borenshult and one at Motala raise the canal to the level of Lake Vetter, nearly 50 feet higher than Lake Boren. The vessel in the lock is the Astrea, 263 tons gross. Originally the Viktor Rydberg, built in 1885, she has a length of 97 ft. 7 in., a beam of 21 ft. 11 in., and a depth of 9 ft. 6 in.

After this lighthouse has been passed the ship threads her way between a maze of islands and rocks towards the lovely Sound of Sävö (Sedge Island), and then passes through an extremely narrow passage called Stendörren (“Stone Door”). Vessels steam past rocks so near that a passenger could jump on to them from the ship. The ship generally calls at Oxelösund after having crossed the inlet leading to Nyköping. Oxelösund is an important port for loading iron-

With these dangers safely past her stern the ship leaves the Slätbaken, as the arm of the Baltic leading to Mem is called, and begins her cross-

When the canal was built one problem was how to deal with landowners who did not want to sell land. There was no law to compel them to sell and at one place the small farmers decided that they would not benefit by the canal, and their refusal to sell threatened the whole project.

Instead of trying to force the issue and arousing that stubborn antagonism which sons of the soil are apt to show when any one tries to compel them, Count von Platen adopted more tactful methods. He sent a persuasive representative to meet the farmers. Instead of trying to explain the principles of canal engineering, the representative cleverly appealed to the artfulness of the farmers.

He asked them if they knew that one part of the land was higher than the other. They said they knew that, so he next asked if they had ever seen water running uphill. Nobody had. Then he asked if they had ever seen a vessel going along without water under her, and they said they never had. Then he told them that on their evidence it was clear that the person who intended to bring water uphill and float vessels upon it was not in his right mind, and all they had to do was to sell the ground and take his money. When he found he could not do what he said, they would get their ground back for a song. They saw the force of this and sold the ground, but did not get it back as they expected.

Climb Through Fifteen Locks

The lock at Mem raises the ship about 9 ft. 10 in., and she steams across flat country to the ancient town of Söderköping, now a watering place. Then begins a climb through a series of locks to Carlsborg, after which the scenery is delightful, as the canal is cut into the side of a hill. Klämman (“Squeezed”) Lock is so named because it is squeezed in between rocks and sharp bends in the canal.

The channel widens into the little lake of Asplången and contracts at Hulta Lock. Then comes Bråtom (“Hurry”), and at Björnvadet Bridge (Bear’s Ford) the canal is protected by high banks built to prevent it from being inundated by the overflow from Lake Roxen. Norsholm is the lock through which the steamer passes into Lake Roxen, which has three large feeders and one outflow. When the feeder rivers are in flood the level of the lake rises to an appreciable extent.

After having crossed Lake Roxen to Berg, the steamer enters the next section of the canal and begins a stiff climb through fifteen locks in a distance of 2,597 yards, rising about 30 feet. This takes an hour and three-

The vessel finishes the ascent at Heda Lock, and the passengers look down upon Lake Roxen and later see the Motala River. Winding her way through the fields, the ship approaches Lake Norrby. The ship does not enter the lake as the canal is separated from it by a narrow bank. The canal is so high above the lake that the tops of trees on the lake-

On her way across the crystal-

A pretty story is told of St. Bridget’s grandmother, Sigrid the Fair. One of the younger brothers of Birger Jarl, a proud noble, married Sigrid, whose family were “beneath” his. The bridegroom kept his marriage quiet, but his brother heard of it and sent the bride a wedding gift of a cloak. Half the cloak was of gold cloth and the other half of cheap material, to signify his opinion of the match.

The bridegroom had gold and jewels embroidered on the cheap half, making it more valuable than the other half, and sent the cloak back to his brother. The Jarl, enraged by this rebuke to his rudeness, set out to find his brother, but the bridegroom left his home and told his bride to receive the angry man. She was so modest and beautiful that the Jarl realized his fault and apologized.

ENTRANCE TO LAKE BOREN at the eastern end is made through a lock at Borensberg. Here also is a regulating lock to control the supply of water for the canal. The Pallas is one of the passenger steamers of the Göta Canal Company which ply between Stockholm and Gothenburg. Other steamers ply between Stockholm and Jönköping.

At Borenshult, at the end of Lake Boren, five locks raise the ship in the canal cut across the neck of land to Lake Vetter. Although the distance is under three miles the steamer takes about an hour to lock through and reach Motala, which is in beautiful country. The town was created by Count von Platen, who intended to found three others, but Motala is the only one which flourished, becoming famous for its engineering shops and ironworks. Von Platen is buried at Motala, which marks the end of the East Göta Canal.

Lake Vetter, 289 feet above sea-

Jönköping, the town at the south of the lake, is the home of the safety match, and is an important manufacturing centre. It is the terminal port for some of the vessels from Stockholm. Other vessels go from Motala to Vadstena and Hästholmen (Horse Island), on the eastern shore, and across the lake to Hjo. Vadstena first rose to fame from the convent established by St. Bridget, on the site of which a lunatic asylum now stands. St. Bridget died in 1373 and was canonized twenty years later. The castle at Vadstena was built by Gustavus I, whose son Magnus threw himself out of a window of the castle to catch a “lovely female form rising out of the lake”. He had been deceived by the mists, but was rescued in time.

The main route of the steamers is across the lake from Motala to Karlsborg opposite. Here the West Göta section begins at Rödesund, with a short strip of canal which links Lake Vetter with Lake Botten. Forsvik Lock takes the ship up to the summit of the canal, which is the level of Lake Viken. This level varies according to conditions, the maximum altitude being 300 feet above the sea.

Lake Viken, access to which had to be blasted through the rock, is a delight to the eye but a source of worry to the canal engineer. Crowded with small wooded islands and rocks, it pleases the passenger but, until a channel was blasted out of it, was an extremely troublesome section of the canal. Dynamite and dredgers improved the navigation in 1904. The lake supplies the water for the canal through Vestergötland, but sometimes the level falls too low and the authorities have obtained the right in an emergency to use water from Lake Unden, which is higher than Lake Viken.

At Tåtorp the ship enters a section called the “Rock Canal”, which is narrow and beautiful. Beyond Land-

Lake Vener is navigated in all directions by steamers and a number of canals lead into it, the most important being the Dalsland Canal, which extends from the frontier of Norway.

Sweden’s Largest Lake

The only navigable outlet to the sea is by the Trollhätte Canal, and the steamer from Sjötorp has the choice of several ports of call on the way to Vänersborg, where she enters the canal. The shortest route between the two lake ports is over seventy miles.

Vänersborg lies at the southern end of the lake, near where the River Göta leaves it. The ship crosses the small lake of Vassbotten and passes through “Charles’s Ditch” to the locks at Brinkebergskulle for a descent of a few feet and then enters the River Göta. She steams to the famous locks at Trollhättan (“The Witch’s Cap”), built to avoid the falls. The steamer proceeds by the river to Åkerström, where she avoids another waterfall by a short strip of canal, with one lock.

The last waterfall, at Lilia Edet, is avoided by a lock, the last of the seventy five locks on the route from Stockholm. The way is now clear for the run to Gothenburg through attractive scenery. The steamer takes about two hours to pass the locks at Trollhättan. The falls provide power and the generating station — the most important for the Gothenburg district — supplies electricity to various industries in the town and to the countryside. The rebuilt canal enables ships of 1,350 tons burden to reach Lake Vener. At Gothenburg canal steamers berth in Lilla Bommens Harbour.

THE SÖDERTELJE CANAL connects Lake Mälar, west of Stockholm, with an arm of the Baltic Sea called Hallsfjärden. Work was begun on this canal in 1807 and it was finished in 1819 under the direction of Eric Nordvall. The canal was widened in 1913-

The canal route has helped to make Gothenburg the premier port for Sweden’s exports by affording cheap transport from the interior. The town was created by King Gustavus Adolphus more than three centuries ago, and is the second city of Sweden. The entrance from the Kattegat and the North Sea passes an archipelago and the fairway leads to the mouth of the River Göta. The channel is dredged to a depth of 33 feet with a width at bottom of 500 feet. The total length of the harbour is seven and a half miles. There are a free harbour, as at Stockholm, and basins for large liners, North Sea, Baltic, Mediterranean and coastal shipping and the inland waterways vessels.

The first passenger steamer on the canal was the Admiral von Platen, which made her maiden voyage in 1834. She had a beam engine which developed 38 horse-

On one occasion when the engine stopped the captain called in the aid of the engineer of another vessel. The engine was started, and after that the captain determined to keep it running. When the vessel reached the next port where wood was to be loaded the captain steered the ship in circles and every time she grazed the pier the wood was thrown on board. Sometimes the ship was in trouble because the engine could not be stopped, so an anchor was always ready to be dropped aft to prevent the vessel from butting the lock gates. The first screw steamer was the Linköping, put into service in 1846.

GÖTA CANAL SYSTEM

Length of route from Gothenburg to Stockholm: 347 miles

Length of canalized sections: 115 miles

Greatest altitude: 300 feet

Number of locks: 75

Trolhätte Canal completed in 1800

Södertelje Canal completed in 1819

Göta Canal completed in 1832

Average width at bottom: 46 feet

Average width at surface: 85 feet

Average depth: 9 ft. 10 in.

The passenger service is now maintained by the vessels of the Göta Canal Steamship Company, of Stockholm, founded in 1868. A typical canal steamer is the Juno, built at Motala in 1874 and rebuilt at Stockholm in 1904. She is an iron and steel vessel of 266 tons gross. Her length is 97 ft. 4 in., her breadth 22 ft. 1 in. and her depth 9 ft. 4 in. She is a three-

Several other steamers are available for passengers. These include the Pallas, 256 tons, built at Motala in 1885; the Geres, 255 tons, also built at Motala in 1885; the Astrea, 263 tons, built at Norrköping in 1885; and the Wilhelm Tham, 284 tons, built at Motala in 1912.

The service between Stockholm and Jönköping is normally maintained by the steamers Motalaström, 266 tons, built at Norrköping in 1855 and rebuilt in 1869, and by the Primus, 242 tons, built at Motala in 1876. There are also numerous vessels used exclusively for freight.

The average annual number of passengers in the vessels of the Göta Canal Steamship Company is over 17,000. The commercial traffic also is considerable, the system being used by motor vessels and barges. Begun before the steam railway was a commercial proposition, the canal route has adapted itself to changing conditions, and is an interesting illustration of the development of inland water transport. For centuries the Swedes have been expert river men, using the waterways to float timber rafts from the vast forests, and they are past masters in the art of getting the greatest amount of cargo through the least water. The intricacies of the river and lake route demand constant alertness not only from the captain, but also from the engineers of the vessels, as any slackness in telegraphing the engine-

RIVER AND CANAL AT BORENSHULT. The Motala River, seen on the left, is the river at the western end of Lake Boren. Just north of the river mouth, the canal is formed again by a series of five locks. Steamers take half an hour to mount the locks and another half hour to reach Motala, where the canal emerges into Lake Vetter.

You can read more on “The Caledonian Canal”, “The Kiel Canal” and “Mariehamn’s Grain Fleet” on this website.