© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

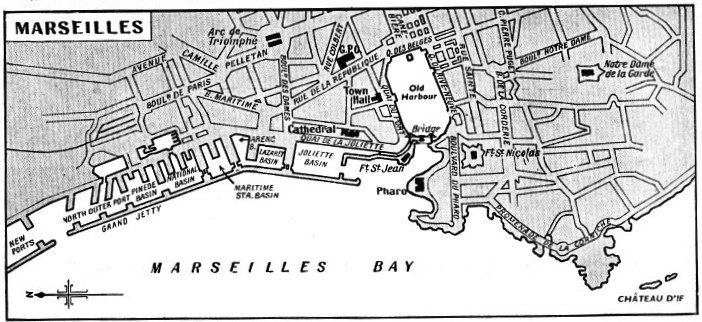

Marseilles: France’s Key to the Mediterranean

Marseilles, the busy and cosmopolitan port which is now a centre of flourishing sea-

DOMINATING THE JOLIETTE BASIN is Marseilles Cathedral, the building of which was begun in 1852. The quays of the Joliette Basin have a total length of 8,143 feet. In the foreground is the Ville d’Ajaccio, a vessel of 2,444 tons gross, built in 1929. She has a length of 269 feet, a beam of 41 ft 1 in and a depth of 22 ft 8 in. This steamer belongs to the Compagnie Marseillaise de Navigation a Vapeur.

OF the great world seaports we know to-

About 2,500 years ago, in the sixth century B.C., the Phoenicians were the great shipowners of the world, and they doubtless knew the harbour which lies so snugly to the east of the mouths of the River Rhone. Probably their strange-

Although the Phoenicians knew this magnificent harbour from the earliest times, the credit for founding Marseilles does not belong to them. For at that dim date in European history, 600 B.C., a convoy of Greek merchant ships came sailing northwards into the Gulf of Lions. Those on board were seeking some place for a settlement and a permanent market, in which they might barter finished goods — ornaments and weapons — for the rich raw materials brought down the valley of the Rhone by the Gauls. These Greeks came from Phocaea, in Asia Minor, not as conquerors but as traders and settlers.

First of all, these Phocaean Greeks probably struck the mouths of the Rhone, but the anchorages there were too full of silt and sandbanks to show much promise as the site of a future seaport. So they cruised eastwards again along the coast until they, too, came upon that sheltered inlet of the tideless Mediterranean, forming a perfect natural harbour. Here, then, they set up their market, and here they laid the foundations of their city to be the most westerly outpost of the ancient Greek civilization. They called the place Massalia. That was the beginning of Marseilles.

As the centuries rolled by, the mighty Roman Empire began to spread over Europe in all directions. It crept along the southern coasts of Gaul, and under its sway the old Greek settlement grew and flourished. The Romans slightly altered the spelling of its name, and it became Massilia.

Under the Romans, Marseilles became a formidable rival to the Phoenician seaport city of Carthage, and in due course the Romans came into conflict with the ambitious and warlike Carthaginians. The Punic Wars broke out, and there was a long and bitter struggle for supremacy in south-

THE QUAI DU PORT, or Harbour Quay, forms the northern boundary of that part of Marseilles Harbour known as Le Vieux Port, or the Old Harbour. This basin has a water area of 65 acres, a length of 2,920 feet and an average width of 1,049 feet. Across its entrance, which is 229 ft. 6 in. wide, is the transporter bridge, illustrated below. The total length of quays in the Old Harbour is 6,210 feet, and a multitude of craft, large and small, may always be seen there.

Nowadays we know Marseilles —Marseille to the French — as a link in the Imperial route between Great Britain and the East, for many people travelling to India and the East save several days by taking a special train across France and picking up the P. and 0. steamer at Marseilles. The Romans used the port in much the same way for conducting passenger and freight traffic between Britain, Gaul and their own mother country. In the first century A.D., a great straight Roman road — Watling Street — ran from Wroxeter (Salop), through London, to Dover. From Calais, or Portus Itius, as it was then called, another straight Roman road led southwards through Gaul. And from Marseilles the great sea-

In our own times, Carthage is an uninhabited wilderness of ruins; we hear oftener of Genoa than of Ostia; Sidon has passed to make way for modern Haifa. In Great Britain, the ancient port of Rye is not even on the seacoast to-

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the fortunes of Marseilles were shaky for a time, but in the tenth century its second foundations were laid and it has flourished ever since, in spite of a stormy history during the Middle Ages, and again during the French Revolution. Marseilles is to France what Glasgow is to Great Britain.

A Stormy History

As with all great international ports, Marseilles seems to have a nationality peculiar to itself, a nationality compounded of all the hundred and one different races which use it. French it is in name, but thousands of its inhabitants who speak French as their everyday tongue and call themselves Frenchmen are of such types as Arabs and Moors, Senegalese, and men from Cochin China.

As for those who do not claim French nationality, they belong to every race under the sun. They will be found lounging on the quays, leaning over the bulwarks of ships from the other side of the world, refreshing themselves in queer little eating and drinking houses, riding off into the city in taxis with money in their pockets, returning to their ships by tram with nothing.

Among these men are huge Swedes with yellow hair; almond-

Imagine these and other samples of the world’s population set down on the seemingly interminable quays of this great brown-

THE TRANSPORTER BRIDGE, which crosses the entrance to the Old Harbour of Marseilles, has a span of 540 feet. The bridge is 164 feet above the water, and its towers are 282 feet high. The platform which carries the traverser has a length of about 870 feet. The bridge was designed by M. Arnodin and built in 1905 In principle the transporter bridge resembles others of its type but its position makes it a prominent feature of the port.

The British traveller or visitor arriving at Marseilles for the first time in his life often approaches it from the landward side, by rail or road. This is an unfortunate necessity, made so by the geographical position of Great Britain in relation to the south of France. The proper way to approach Marseilles, the way the sailor knows, is from the blue and silver Gulf of Lions, which was known to the Greeks and the Phoenicians in days before Rome became great.

The city lies on the eastern side of the harbour, and off-

Every great seaport, and every little one for that matter, has its landmarks. These are not wanting at Marseilles. The city’s public buildings are of little interest to the antiquary, but they make up for their comparative and not inspiring newness by a striking prominence of situation. Perhaps the most remarkable landmark is the church of Notre Dame de la Garde. It stands on the summit of a hill to the south of the Old Harbour with its bell tower crowned by a huge copper figure of the Virgin Mary. The “Good Mother”, as the figure is often called, is the same to Marseilles as the statue of Liberty (also a French production) is to New York Harbour. It is visible for miles where it stands, high above the city, seeming to cast a benevolent eye over the vast quays below, as if welcoming home the returning voyager or hailing the newcomer. Seamen of all races, and perhaps of all religions, will speak with real affection of the brooding copper statue of Notre Dame de la Garde.

Sinister Quarter

The Old Harbour lies to the south of the more modern quays, an oblong basin running roughly from west to east, with the mouth at its western end. The harbour has a water area of 65 acres, a length of 2,920 feet and a mean width of 1,049 feet. The depth varies from 11½ feet to 24½ feet. There are 6,210 feet of quayage. An annexe, known as the Bassin du Carenage, has a water area of 3¾ acres and 1,811 feet of quays.

The entrance to the Old Harbour is hidden from the southern approach by the Pharo Palace, once a residence of the Empress Eugenie and now housing the School of Colonial Medicine. The palace stands on a promontory jutting out into the main, or natural harbour. The harbour entrance lies behind this, guarded by an old fort, the Fort St. Jean, on the north side, and by the Fort St. Nicolas on the south.

Beyond these again, and spanning the mouth of the Old Harbour, is the huge transporter bridge, another of the great landmarks of modern Marseilles. This bridge does not differ materially from that which spans the Mersey between Runcorn and Widnes, or from any other big bridge of its type; but for all that it is one of the most striking features of the port, so far as the eye is concerned. It was designed by M Arnodin and built in 1905. The two towers are each over 282 feet high, and the high-

THE PORT OF MARSEILLES has largely been won from the sea This was done by building the Grande Jetee du Large, or Grand Jetty, which forms the seaward wall of the more northerly dock basins. The jetty has a length of 4,519 yards, or more than two and a half miles. The three outstanding landmarks of Marseilles are the cathedral, overlooking the Joliette Basin, the transporter bridge at the entrance to the Old Harbour and the church of Notre Dame de la Garde, to the south of the Old Harbour.

Yet another great landmark seen on entering Marseilles by sea is the Cathedral, an ornate Byzantine building which rises into a succession of domes above the quays of the New Harbour. It belongs to that period — dubious where architecture is concerned— which in England we label “Victorian”, and is new in relation to the hoary age of the city that it graces. But of its kind it is an imposing building enough, and a prominent feature of the background to the crowded cosmopolitanism of the quays.

In considering the dockland proper of Marseilles, we cannot do better than to look, first, at the Old Harbour and the Old Town, which are known collectively to the inhabitants as Le Vieux Port. No visitor to Marseilles should fail to explore this region, but his exploration should be done with circumspection, On the waterfront we are in the midst of the cheerful bustle of maritime activity, among familiar funnels, masts and derricks, constantly within earshot of the friendly clatter of steam winches. But up the back streets things are different.

The newer docks of Marseilles, which lie to the north of the Old Harbour, have a truly colossal extent. The Port of Glasgow was reclaimed from the land, with its formerly unnavigable river, but the Port of Marseilles has been recovered from the sea. On the seaward side the Docks are shut in by huge moles or jetties running parallel to the water-

To the south lies the Joliette Basin, spread out in the morning shadow of the great domed cathedral. The Joliette Basin has a water area of 54 acres. Its length is 1,640 feet and its width 1,312 feet. The depth of water varies from 13 to 33 feet. There are 8,148 feet of quays. Here we find the red-

The Joliette Basin is also the starting-

To the north of the Joliette Basin lies the Lazaret Basin, and here we find a calling place for liners of the Japanese Nippon Yusen Kaisha, and for steamers of the Anchor Line, the Union Castle Line and the City Line. The Lazaret Basin and the smaller Arene Basin, separated by a mole, have a combined water area of 46 acres. The Arene Basin is notable for its enormous grain elevators and storages. The new elevator alongside Dock C of the Arene Basin contains fifty-

Jetty Over 21 Miles Long

The Peninsular and Oriental steamers berth in the Gare Maritime (Maritime Station) Basin, farther north, which, as its name denotes; connects with the Harbour Station, whence come the great express and mail trains from Calais and Boulogne. The Gare Maritime Basin has a water area of 441 acres and a depth in dock varying from 29 ft. 6 in. to 32 ft. 8 in. It is 1,715 feet long and 1,200 feet wide. There are 7,650 feet of quays. The Gare Maritime Basin is the starting-

Going northwards again in our survey, we come to the great National Basin. This has a water area of 102¼ acres. Its length is 3,034 feet and its width 1,689 feet. The depth varies from 11½ to 52½ feet. Length of quayage amounts to 13,000 feet. Here berth British steamers belonging to the Bibby Line, Spanish vessels bound for the River Plate, and United States steamers. On the north side of the National Basin lies the Pinede Basin. Its water area is 66 acres and its dimensions are 1,968 by 1,640 feet. The depth increases from 26 to 65½ feet. There are 10,584 feet of quays. From the Pinede Basin sail the Rotterdam Lloyd steamers, homeward-

The farther north we go along the water-

Such, briefly, is the Port of Marseilles; hoary in its antiquity, yet equally startling in its modernity; a bright yellow city of sunshine.

AN AERIAL VIEW of the dock system at Marseilles, looking north. In the foreground is the Old Harbour, with its annexe the Bassin du Carenage. Farther north are the Joliette and Lazaret Basins, and beyond the angle come the Arene, Gare Maritime Nations and Pinide Basins Still farther north are the more recent additions to the dock system.

You can read more on “French Shipping”, “The Suez Canal” and “The Triumph of the Normandie” on this website.