© Shipping Wonders of the World 2012-

Pidgeon and the “Islander”

The first man to sail on a single-

GREAT VOYAGES IN LITTLE SHIPS -

PIDGEON’S 34-

TO sail round the world single-

During his voyage Pidgeon met Gerbault at Balboa, on the Pacific side of the Panama Canal. Gerbault’s voyage is described in the chapter “Gerbault and the Firecrest”. The vessels and temperaments of the two circumnavigators were in marked contrast.

Neither Gerbault nor Pidgeon is a sailor by profession; but Pidgeon is as handy a man as Slocum was. He can use his hands to make and rig a boat. He was thus able to make his voyage at less expense and trouble than Gerbault, because Pidgeon did most of his fitting for himself and started with a new yacht. He tells the story of his adventures in his book Around the World Single-

Born on a farm in the Middle West and not seeing the sea until he was a youth of eighteen, Pidgeon started from scratch so far as seamanship was concerned, and his first adventures were on fresh, not salt water. He and another young farmer went to Alaska one summer, cut planks out of a spruce tree and built a boat.

The small-

Pidgeon’s problem was to find a seaworthy design which he could build without obtaining elaborate appliances or using methods which were beyond his powers as an amateur. He found what he wanted in a V-

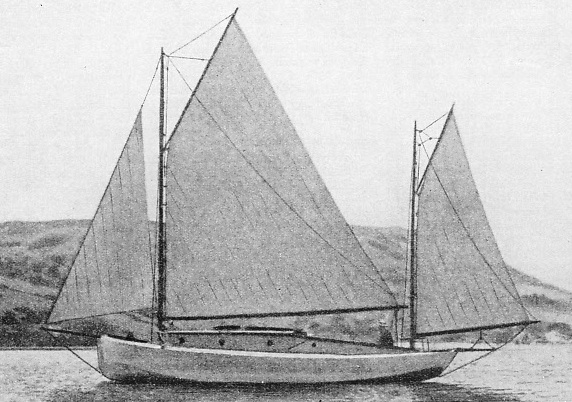

He modified and altered the designs in some details according to his ideas and to the extent of his resources of cash and material. Nearly all the wood was Douglas fir or Oregon pine, the stem being oak. An iron keel weighing 1,250 lb. was bolted to the keel timbers. The Islander was 34 feet long, with a beam of 10 ft. 9 in. and a draught of 5 feet.

HARRY PIDGEON HEWING OUT KEEL TIMBERS for the Islander in 1917. The timbers were 8 in. wide and 12 in. thick; the longest measured 28 feet. They were cut to shape with saw and adze, and were bolted to the 1,250-

Because of the design the hull was shallow, and to obtain head room in the cabin a coach-

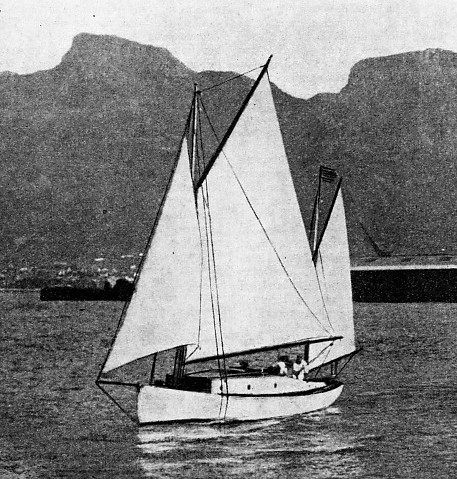

The vessel was yawl-

After her launch, Pidgeon tested her and then settled down to the study of navigation. He decided to take the sun as his guide and to eliminate stellar work. His instruments comprised a sextant, two compasses, a patent log, and two watches, one for Greenwich time and the other for ship’s time. He did not use logarithm tables, as is the practice of British navigators, but tables which enabled him to establish longitude by chronometer by another method. He had the usual parallel rules, protractor and dividers for chart work, but he lacked charts and pilot books for some waters.

He determined to sail to Hawaii to get experience, and reached Honolulu in twenty-

The stores problem was vital, and Pidgeon made no mistakes. His water-

His previous adventures had taught him much about rationing, so that his victualling was excellent. He burned wood in his stove, and never had any trouble with that. He had a small hand mill to grind the wheat and corn which he used instead of bread and ship’s biscuits. He stored beans, peas, rice, dried fruits, and sugar in moisture-

Beginner’s Luck

Pidgeon carried an adequate quantity of bacon and, although he had tinned salmon, milk and fruit, he always used these as little as possible, preferring native food when he could get it. He ate native fruit and vegetables, as well as potatoes and onions.

He had good luck at the start. He sailed out of Los Angeles before a fair wind and got south in time to escape the worst storm on the coast for years. The going, however, was rough. Once he gybed and was stunned by a reefing cleat which struck him behind the ear. The gale became so strong that he furled all sail except the storm jib, which he hauled flat amidships, lashing his tiller and letting the Islander blow before the wind. This storm lasted for three days, but Pidgeon always managed to cook on his wood-

In the Doldrums he cut his sleep short so that he could be ever on the alert to make the most of the squalls that breezed up between the calms. Once he made only a mile in twenty-

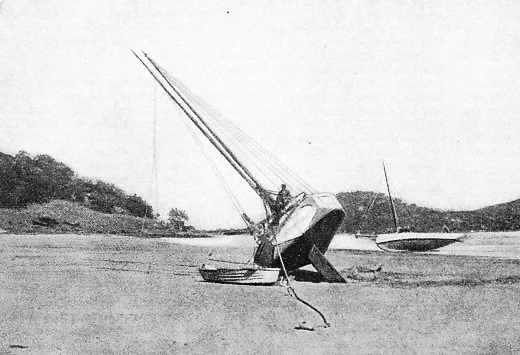

BEACHED FOR REPAINTING on Prince of Wales Island, in the Torres Strait, between Australia and New Guinea. Here Pidgeon cleaned the Islander’s hull and gave her a coat of copper paint. The yacht’s deep keel gave her a good list when beached. Her dinghy, 9 feet in length, is seen alongside.

Pidgeon spent four months in the Marquesas. The Islander was not copper-

Nukuhiva is notorious for the nau-

Not having a chart of the Tuamotus, or Low Archipelago, a group of low-

After a cruise among the Society Islands, of which Tahiti is the chief, Pidgeon’s next passage was to Samoa. From there he sailed to Fiji, but broke his boom during a squall. He repaired it by nailing strips of boards round the two broken parts and lashing rope round so that the boom lasted for the passage to Fiji. Here he made a new boom, had the Islander hauled out of the water on a slip and cleaned and painted his ship again.

During his stay in Fiji, Pidgeon nearly came to grief. He was waiting in the islands for the end of the hurricane season when there came a warning of a hurricane. Pidgeon was recommended to sail to a comparatively safe cove, but ran aground, so that the Islander was left on a ledge by the falling tide. He managed to get her afloat on the next tide, but his anchor was fouled, and he had to slip the anchor chain and buoy it, recovering his anchor later. The hurricane missed Fiji, so that Pidgeon had all his trouble for nothing; he did not grumble about that as he was too thankful that a storm had not arisen when his yacht was on the ledge.

After the end of the hurricane season, Pidgeon sailed for the New Hebrides and then for Port Moresby, New Guinea. Here he was in danger because of his lack of charts. The keel of the Islander grated on coral, but Pidgeon managed to sail off the reef and get into Port Moresby. Again the Islander had a narrow escape. Pidgeon was ashore one evening and returned to the beach when a gale was blowing offshore.

To his alarm he could not see the Islander. Search was made in a launch, and not until daybreak was the truant seen. The stock of her anchor had broken, and she had drifted clear of a reef until the broken anchor had caught on the reef and held. On another occasion Pidgeon brought up alongside a native ketch and took the ketch skipper’s word that there were 9 feet of water. The tide fell and the swell bumped the keel of the Islander on the bottom. Pidgeon hurriedly set his sails, weighed his anchor and managed to claw off into deeper water.

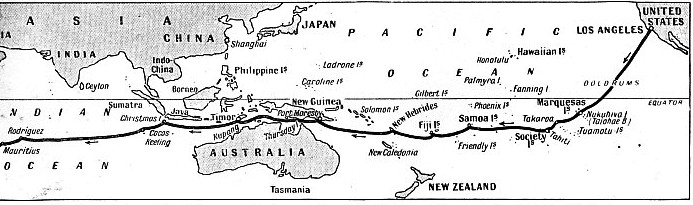

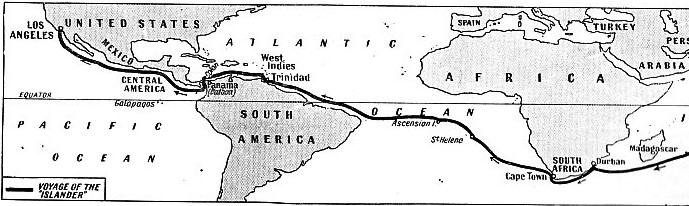

PIDGEON’S VOYAGE ROUND THE WORLD started at Los Angeles (extreme right of this map, above) on November 18, 1921. Forty-

When Pidgeon reached Thursday Island to refit, he debated whether to go south to Australia or to return to Los Angeles by way of South Africa and the Panama Canal. He decided on the latter plan. He sailed to Ku-

He reached the Cocos-

At the island of Rodriguez Pidgeon had news of the Shanghai again, and also of the feat of the two boats of the Trevessa, whose heroic adventures are described in the chapter “Heroes of the Trevessa”. Captain Foster’s boat reached Rodriguez after having sailed more than 1,500 miles across the Indian Ocean.

Pidgeon took a pilot at Rodriguez. When he decided to sail he found that the pilot had let go both anchors so that they fouled the deep-

AT CAPETOWN, IN TABLE BAY, the Islander underwent repairs to her rudder and part of her keel, which had been damaged when she was driven ashore over some rocks. Her total sail area was 633 feet. The cabin was 12 feet long; the sides of the coach-

His next port was Durban, South Africa, where he berthed just before Christmas. He did well with lantern lectures and when he sailed for Capetown he was in funds. His passage to the Cape was a rough one, and he was hove-

After a happy time in Capetown Pidgeon set out for St. Helena, but was stranded before he had gone far. The wind was light and he could not get off the land. On the third night out, when he thought he was farther off the shore, he turned in and was awakened by the shock of the Islander taking the ground. While he was sleeping the wind had changed and blown the yacht ashore. No single-

Ready aid was forthcoming and the Islander was towed off. She returned to Capetown, where Pidgeon repaired the damage in three days. His account of the kindness with which he was treated in South Africa is a tribute to the sportsmanship of the South Africans. He says that when she left for the second and last time she was in better condition than when she had set out from Los Angeles. He followed Slocum’s track to St. Helena.

Pidgeon sailed on his lonely way and touched at Ascension Island. One night he had a fright. He awoke to find water over the cabin floor, and thought his yacht was sinking. A lantern had fallen against the tap of the water cask, and had turned on the water. Fortunately he woke up in time to save most of the water.

Even more alarming was an encounter with a steamer in a fresh breeze at night. The vessel saw the Islander, and as the officers thought the little vessel was in distress they ran alongside and bumped into her with a force that awoke Pidgeon. He fell into the cockpit, and was hit over the head by the end of a rope which his zealous rescuers had thrown down. Before Pidgeon had made it clear to the officers that all he wanted was sea-

Pacific Waters Again

Next lie sailed to Cristobal (Panama), his chief anxiety being to avoid “rescuing” steamships. At Cristobal Pidgeon encountered another problem, which was how to get through the Panama Canal to Balboa. A tug would have cost him £1 an hour, and as yachts are not allowed to sail through he was in a dilemma. The solution was an outboard motor which was lent to him by a friend.

The Islander passed the first set of locks at Gatun, but then the outboard motor failed, so Pidgeon sailed to the next lock, where he was met by his friend. The friend got the outboard going, and at length the yacht reached Balboa. Here Pidgeon met Gerbault.

With birds and fish for his only companions Pidgeon slowly forged ahead. Eighty-

Neither Slocum nor Pidgeon, nor even Gerbault had an auxiliary motor. Slocum lived before the time of the efficient motor engine. Gerbault wanted to achieve the voyage without such aid, and Pidgeon states that he could not afford one and also that he was no mechanic. Each of the three yachts went ashore and, but for fine weather and good luck, would have broken up. Slocum was stranded because he hugged the shore too closely one night to avoid an adverse current, and Pidgeon and Gerbault were asleep at the time of their mishaps.

It is impossible for any single-

The single-

All three single-

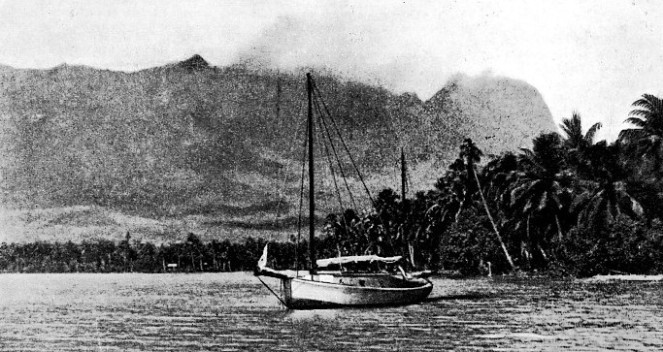

ANCHORED IN PAOPAO BAY, Moorea Island, near Tahiti. The strange peaks of Moorea are visible from Papeete, where Pidgeon spent about four months. He sailed the Islander across to Paopao Bay when he continued his journey to Samoa.

You can read more on “Captain Slocum the Pioneer”, “The First Voyage Round the World”, and “Gerbault and the Firecrest” on this website.